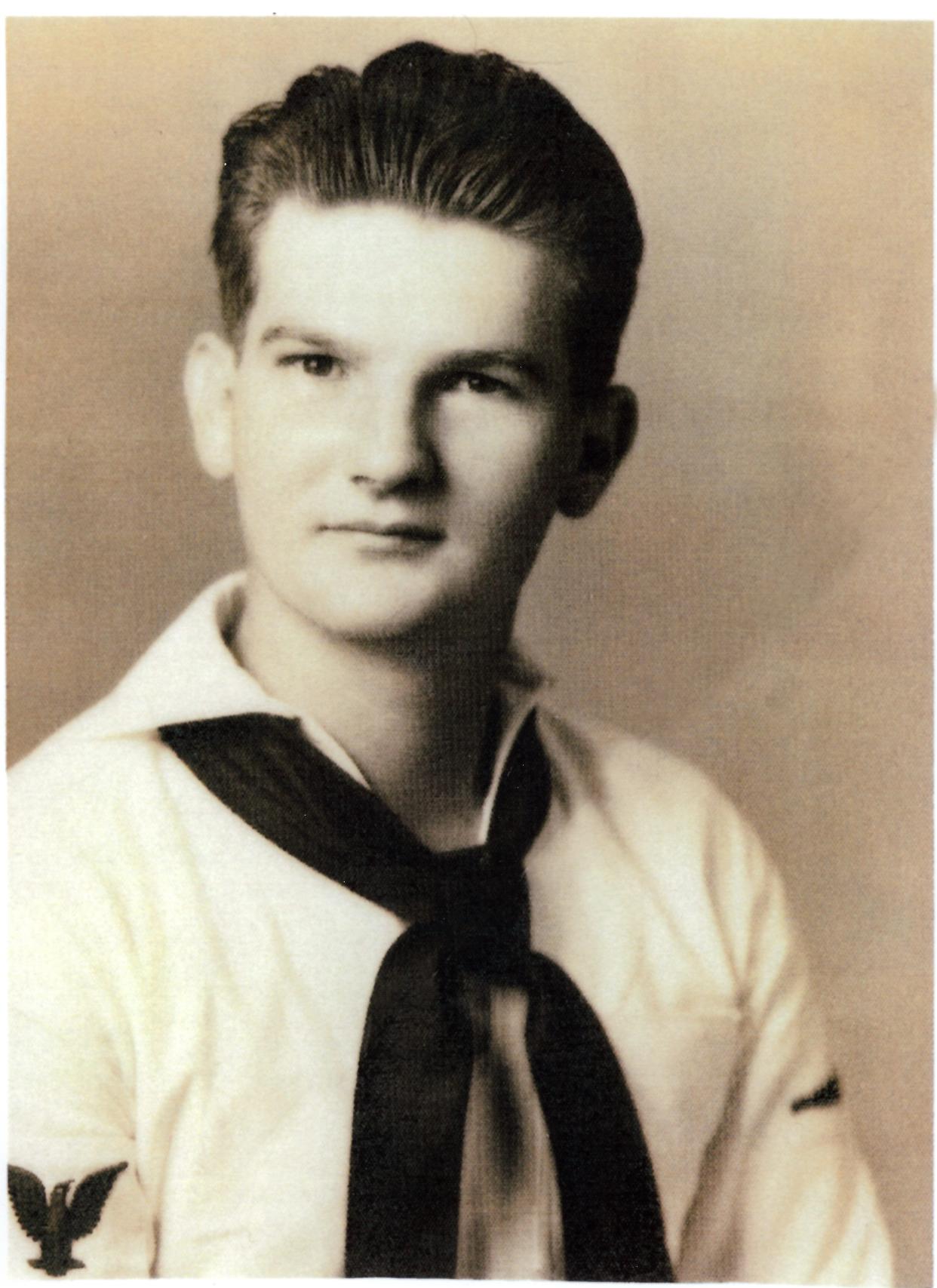

Remembering Pearl Harbor 80 years later: The story Paducah man, James Vessels | Opinion

James Allard Vessels of Paducah was enjoying a friendly Sunday morning card game with a shipmate on the battleship Arizona in the middle of Pearl Harbor.

More than 4,200 miles away in Fancy Farm, it was Sunday afternoon. His fiancée and childhood sweetheart, Frances Anita Hodge, couldn’t wait to model the new engagement ring her betrothed had sent from Hawaii.

The date was Dec. 7, 1941, when Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor plunged America into World War II. Vessels, 21, lived. His ship died. So did 1,177 of his fellow crewmen, including Vessels’ card partner, a sailor named Lightfoot.

Vessels was the first of about a dozen Pearl Harbor survivors I interviewed during my tenure at the Paducah Sun-Democrat and Paducah Sun. Their stories formed the nucleus of my book, "Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy," which the University Press of Kentucky published last year.

More: 80-year mystery laid to rest on Memorial Day: A Pearl Harbor casualty comes home

His warship is the most iconic of the all the vessels lost on the date President Franklin D. Roosevelt said would “live in infamy.” A gleaming white memorial straddles what is left of the Arizona’s rusty, bomb-blasted, fire-blackened and submerged hull.

The air raid began shortly before 8 a.m. “Lightfoot and I jumped up to see what was going [on] as we couldn’t figure [out] what was happening,” Vessels said.

The crew raced for battle stations. Vessels' was “the birdbath,” an anti-aircraft machine gun position atop the mainmast. A dizzying 90-feet above the waterline, it was the loftiest spot on the ship.

Vessels and his fellow machine gunners made it to the top. But bomb fragments and strafing fire killed or wounded several other sailors and marines as they scrambled up the mast’s steel legs to their battle stations elsewhere on the mainmast. “Guys were droppin’ off the ladders like flies,” a survivor remembered.

Because it was peacetime, the machine gun ammunition was stowed below. So Vessels and his mates watched helplessly as enemy horizontal- and dive-bombers worked over the Pacific Fleet.

About 15 minutes into the attack, an armor-piercing bomb crashed through the Arizona’s forward deck into a powder magazine, triggering a fiery explosion that heaved the 32,600-ton capital ship’s bow section nearly 50 feet into the air.

The concussion “tore most of our clothes off,” Vessels said. “But if we hadn’t been up in the mainmast, we wouldn’t have made it.”

After the fires subsided, Vessels and his shipmates began the long climb down. On the anti-aircraft deck, he saw just one man standing. He was badly burned, but Vessels recognized him as Lightfoot, whose injuries were fatal.

A machine-gun bullet from an enemy plane had hit Vessels in his right leg. He cut it out with his pocket knife.

James Allard and Frances Anita returned to Pearl Harbor for the 30th anniversary of the attack, and they visited the Arizona memorial. Beneath their feet were the remains of more than 900 crewmen still entombed in the battleship, as well as Vessels’ shipboard belongings. He was thankful he didn’t lose her engagement ring and wedding band, which he bought in Honolulu. The sailor mailed them to his parents in Paducah with instructions to pass them on to Frances Anita and her parents.

More: Officials identify remains of Kentucky sailor killed in Pearl Harbor attack

The future in-laws agreed on a delivery date: Dec. 7. They would worship together at St. Jerome Catholic Church, then have Sunday lunch at the Hodge house.

It was a little before noon in western Kentucky when the Pearl Harbor attack started. Mass was probably over at St. Jerome, and James Allard and Frances Anita’s folks had likely started the midday meal.

Afterwards, Frances Anita tried on her diamond ring, and everybody gathered around the radio. “They were listening to music, and all of a sudden it came over the radio that Pearl had been bombed,” said Margaret Vessels Shoulta, one of James Allard and Frances Anita’s two daughters. “It was just devastating.”

News bulletins reported that the Arizona was sunk. But there was no word about casualties. For about two weeks, the families prayed that their loved one was alive but feared he was dead.

Shortly before Christmas, Walter and Annie Mae Vessels were overjoyed to receive a short letter from James Allard promising he was okay. He earned a brief leave to come home in February 1942; wasting no time, he and Frances Anita got married on the 25th. The couple also reared five sons, four of whom, including Mike Vessels, were sailors.

When Mike arrived at Pearl Harbor in 1968, he was astonished to see “these Japanese torpedo planes…flying over, dropping torpedoes, and they were setting off explosions in the water. So I'm here watching what Dad really went through."

Hollywood had come to Honolulu. Crews were filming the movie "Tora! Tora! Tora!" which came out in 1970.

Tom Brokaw hoped "The Greatest Generation," his book about the World War II generation, which included my sailor father and soldier father-in-law, would “in some small way pay tribute to those men and women who have given us the lives we have today.” That was also my hope for my book, which I dedicated to Motor Machinist’s Mate First Class Berry F. Craig Jr. and Master Sergeant Robert P. Hocker Jr., both of whom volunteered after Pearl Harbor and were combat veterans of the Pacific war.

McCracken countian Jim Hamlin, who survived the sinking of the battleship California, was the subject of my second Sun-Democrat Pearl Harbor story. The day after the story ran, he found me in the newsroom.

“Thank you,” he said, handing me a small Christmas fruitcake and shaking my hand.

“No, sir,” I replied. “Thank you.”

Berry Craig is a professor emeritus of history at West Kentucky Community College in Paducah and an author of seven books and co-author of two more, all on Kentucky history.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Remembering the attack on Pearl Harbor 80 years later | Opinion