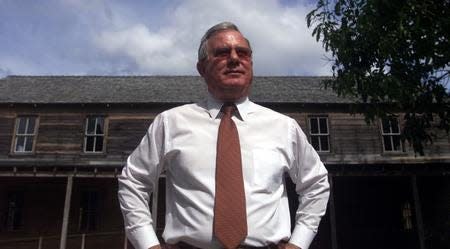

Remembering passionate preservationist, Fort Myers attorney and Koreshan descendant Bill Grace

Fort Myers attorney Bill Grace, a lion of local history, died last week.

A Koreshan descendant, he was “truly the father of preservation in our community,” says Fort Myers historian and educator Gina Sabiston, who counts Grace as her mentor.

Estero Island’s Mound House, Fort Myers’ Burroughs Home, Buckingham’s Flint House and many venerable structures at Koreshan State Park: Grace helped save them all. He spent countless hours sitting through board meetings, educating cub reporters and petitioning politicians. He also was happy to roll up his sleeves and flip pancakes at the Burroughs Home’s annual breakfast with Santa or hackin Brazilian peppers that threatened to choke historic sites.

Grace was a "wonderful, loving person" who put that love into action, notes Alexandra Bremner of Fort Myers. When he believed in something, “he supported it with his whole heart,” she says.

Delivered in Fort Myers by his doctor grandfather W.H. Grace to his doctor father and mother, Angus D. and Eleanor Case Grace on September 17, 1944, Grace was a Fort Myers High Greenie from the class of 1962. Four years later, he wed his high school sweetheart Susan, to whom he’d been married 56 years when he died.

Grace earned a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of South Florida, then it was on to the University of Tulsa for his Juris Doctorate. Grace came home to practice law, becoming the 100th person admitted to the Lee County Bar Association.

The region’s history was in his blood in a very real sense. As a prominent Fort Myers attorney from a prominent Fort Myers family, Grace spoke with the town's distinctive old-guard inflections, a gentle Florida Southern accent seasoned with polite pauses and well-modulated laughter. But get him talking about the often-uphill battles to preserve the region’s past, and a vein in his neck would pulse against his Oxford cloth collar.

More: 'Steeped deep in history.' What you should know about Mound House

More: Midpoint Memorial Bridge celebrates 20 years connecting Cape Coral, Fort Myers after controversy

His ancestors on both sides were associated with the Koreshan Unity in Estero, an idealistic sect of pioneers who carved a would-be New Jerusalem out of the subtropical scrub around the turn of the 20th century. Led by the charismatic Cyrus Teed, who renamed himself Cyrus (Hebrew for shepherd) the cultured and well-educated group valued science and industry while believing that the universe is a hollow sphere with humanity inhabiting its inner surface. In just 15 years, they amassed more than 5,700 acres and built a power plant, a saw mill, bakery, concrete factory, plant nursery, boatworks, art gallery, general store and a state-of-the-art printing plant, among other enterprises.

Because state funding for preservation projects is notoriously hard to come by, Grace joined its citizen support organization in 1985, serving as its president for more than 25 years. During that time, the group helped plan, fund and restore a number of the site’s structures and conducted the first professional archaeological survey of Mound Key, another historic Koreshan and Calusa site in Estero Bay.

More: Preserving the Koreshan legacy

More: Historic Koreshan cottage protected

Grace mastered the art of writing grants, bending ears and otherwise working the system to get things done.Though Grace has had his share of defeats, he raised millions of dollars to restore crumbling buildings at the historic site and his nonprofit became the model for such citizen support organizations around the state.

Yet he was as realistic about the Koreshan failings as he was impressed by their accomplishments. Though Grace credited them with enormous powers of will and intellect, Grace also recalled his grandmother's tales of disease, crop failures and schisms – not that they ever diminished his passion for preserving the Koreshan legacy.

"History will tell you that nothing's perfect," he told The News-Press in 2005. "This country isn't perfect, but that doesn't have to make you ambivalent about it."

When the going got tough, he spoke out, firing off letters to officials and The News-Press to raise awareness of what was at stake. “He could be salty when he had to be,” Sabiston recalls, “but he was a purist and he didn’t compromise.”

He was pragmatic, though, and knew different people brought different strengths. When the historic Towles Home was at risk, for example, he threw his professional muscle into the fight, Sabiston says, using his network and legal savvy to get things done, while she took on the publicity. “I got out there with signs and did a little protest, while Bill met with people,” she says. “And we got it moved.”

He and Susan were adamantly opposed to the Midpoint Bridge, which connects a historic neighborhood in Fort Myers to Cape Coral. Though they lost that battle, he remained steadfast, says longtime history educator and environmental advocate Cindy Bear. “(The couple) vowed to never cross the Veteran's Memorial because of the harm it did to local historic homes and the character of the community,” Bear says, “And, they never did! Very few make such pledges and stick to them.”

The Calusa Nature Center was another of his passions and he served for eight years on its board, including as president, during which he oversaw the construction of its planetarium as the museum doubled in size.

He also was a founding board member and president of the Lee Trust for Historic Preservation, which worked to launch numerous historic districts, including the Downtown Historic District, Edison Park, Dean Park, and Seminole Park and has sponsored numerus restoration and education projects, as well as serving on many other boards, commissions, foundations and other groups that championed the common cultural good.

Yet despite all he accomplished, Grace shunned the spotlight, Sabiston recalls: “He hated accolades.” So his legacy lives in the places he helped preserve and the ethos of those he influenced.

“I’ve tried to model myself after Bill Grace,” she says, “and I hope to continue to do him proud for the rest of my life.”

This article originally appeared on Fort Myers News-Press: Bill Grace's legacy of uncompromising historic preservation