Reimagining Large-Scale Impact Philanthropy: An Interview With Merton Capital Founder Sean Davis

Making philanthropy work the way it is supposed to is one of the perennial concerns of foundations, family offices and just about everyone who navigates the world of non-profits and major giving. Once return-on-capital is removed as the universal common denominator—the one metric reasonable minds of all persuasions can usually agree on as the quintessential measure of success—things tend to get a bit tricky. While it is generally fair to say that the world of large corporate and foundation giving has become much more sophisticated over the past few decades, it is also true that in philanthropy, ultimately whether a project is deemed a success is still very much in the eyes of the beholder.

Nonetheless, many investment professionals, foundation managers and others involved in philanthropy and large-scale family giving at the highest levels are beginning to see that there is still a very large bottleneck that continues to plague the sector: pent-up supply among the world’s mega-donors. Simply put, despite widespread recognition that the world has manifold pressing concerns that could be uniquely solved by the effective deployment of the philanthropic capital of the ultra-rich, the lion’s share still remains locked up because there is no effective means for it to be deployed at scale.

Take, for example, the infamous Giving Pledge, the much-ballyhooed program launched in 2010 by billionaire besties Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. The initiative was meant to be the opening salvo in a campaign to inspire global elites to pinkie swear that they would give away at least half of their net worth to philanthropy, either during their lifetime or upon their death. Despite the scores of bold-faced names that have signed the pledge—everyone from Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal to George Lucas and his wife Mellody Hobson—much of their collective wealth, which has now surpassed the eyebrow-raising sum of half a trillion dollars, remains held up.

And all indications are that the amount of wealth unable to be channeled into large-scale projects will only grow in the years ahead. At present, 219 billionaires have signed on to the Giving Pledge, yet this group of heavy hitters still represents less than 10 percent of the world’s purported 2,825 billionaires; even as the number of global billionaires who either sign on to effort—or effectively embark upon their own track to do the same—the pace with which the world’s billionaire class is accumulating wealth is far outstripping their ability to part ways with it.

Billionaire signers of the Giving Pledge—an initiative started by Bill Gates (L) and Warren Buffet (R) over a decade ago—have struggled to find non-profit impact projects where they can deploy their wealth at scale. Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

A cynical take that explains why so much global wealth has been committed to charitable endeavors yet remains undisbursed is that it is hard to part ways with one’s fortune—particularly one that business owners toiled so hard to create in the first place. But a less cynical and far more practical explanation points to the inherent problem of the Giving Pledge—that there is simply nowhere to put such vast sums of wealth. In other words, oddly, it’s a demand issue; although in theory there is near limitless demand for charitable dollars, in practical terms, once the conversation gravitates to proposed gifts that reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars, the number of non-profits equipped to raise, take in and effectively deploy targeted capital at that level drops off quite quickly.

Worth spoke to several experts in the field of large-scale philanthropy who believe that there are at most 150 non-profit organizations worldwide that have detailed plans at the ready—or the wherewithal to quickly create them—for taking in targeted gifts of $200 million or more and quickly scaling their organizations accordingly to accommodate them. If signers of the Giving Pledge were able to funnel $200 million gifts to each of those 150 organizations–$30 billion in total—it would still amount to less than 5 percent of the $600 billion estimate that is currently pledged by the very same signers.

Take, for example, Michael Bloomberg, founder of the eponymous Bloomberg LP, who, with an estimated net worth of $55 billion, is considered to be a global paradigm of mega-philanthropy and charitable giving. The former New York City mayor has given away almost $10 billion in his life via his foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies; nonetheless, he is still coming up quite a bit short of his own Giving Pledge commitment. Bloomberg’s case is likely complicated by the fact that so much of his wealth is tied up in his privately held company and cannot be easily extracted without selling the firm. Nonetheless, at age 79, Bloomberg would still have to give an amount close to what he has given throughout the entirety of his life every year to stay ahead of his annual increases in wealth to reach his pledged goals.

And Bloomberg is not alone.

The truth is that it is very hard for Giving Pledge signers to keep ahead of their wealth increases; in fact, more than a few signers have passed away without meeting the terms of their pledge which has called into question whether the signers’ commitments can really be achieved in any practical way given that many mega-donors are seeking opportunities to deploy their largess toward critically important projects that have a profound impact at scale.

According to the Bridgespan Group, a management consulting company in the non-profit world, the 2,000 wealthiest families in the U.S. gave 1.2 percent of their assets away in 2017, a relatively meagre sum when compared to the S&P 500’s 20-year average annual return of 9 percent. “The clear-eyed math shows that if an ultra-high net worth family wanted to spend down half its wealth in a 20-year timeframe, the family would need to donate more than 11 percent of its assets per year—a nearly tenfold increase over its current level of giving,” reads the report. No matter how many billions they give away, the uber-wealthy’s giving rates are dwarfed when compared to their annual increases in their own wealth.

At a macro level, it’s the demand side of the equation that is failing to unlock the deployment of more philanthropy investment. This demand bottleneck has been a longstanding thorn in the side of family fortunes that are looking to solve specific issues at scale. And this dynamic is also the main reason that so much large-scale giving generally tends to support existing programs or endowments rather than funding bold solutions to address the planet’s most vexing issues. Take for example Joan Kroc’s historic 2003 $200 million gift to National Public Radio, at the time described as “the largest monetary gift ever received by an American cultural institution.” Yet the McDonald’s heiress’ gift had the squishiest of objectives—“funding the NPR Endowment Fund for Excellence, to provide support for NPR activities independent of other revenue sources”—in other words, supporting the continuation of public radio, more or less.

Kroc’s largess shouldn’t be criticized; there is no doubt NPR was more than happy to make good use of her benevolence. But what about billionaires who want to make a big impact that goes beyond propping up an institution’s endowment? What about the ambitious self-made men and women who want to put their capital to work to address the planet’s most pressing and even existential concerns? This class of philanthropists-in-waiting are most assuredly not getting pitched $200 million ideas on a regular basis. In fact, it quite likely that most have never been on the receiving end of an ‘ask’ for more than $200 million that purports to solve a specific global problem in the way that venture capital would look to fulfil an unmet need in the marketplace. The unfortunate reality is that there are very few non-profits with the capacity for targeting nine- and 10-figure transformative giving.

The unfortunate reality is that there are very few non-profits with the capacity for targeting nine and 10-figure transformative giving.

Finally, the concerns about the inefficiencies of giving at scale comes just as the ultra-wealthy face mounting criticism over the mere concept of philanthropy itself. Dan Riffle who works for Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), made headlines in 2019 by arguing that “every billionaire is a policy failure,” implying, in part, that government is a much better vector for deploying capital en masse than philanthropy—a major talking point of his pitch for placing hefty taxes on the top one percent of wealth holders in the U.S. And don’t forget Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) who continues to make the case for a wealth tax on ultra-high net worth individuals. While many defenders of the free market will argue that government waste is equally if not more egregious, it’s increasingly hard to defend the merits of large-scale philanthropy when there is no reasonable vector for capturing billionaires’ desires for impact giving.

Enter the World of Venture Philanthropy at Scale

It is in this context that a new breed of investment and philanthropy advisors is emerging to help unlock the power of large-scale philanthropy. By employing an investment philosophy that is much more akin to venture capital or private equity than traditional giving, this new generation of “venture philanthropists” are helping family offices and foundations pool capital, identify targets and invest in large-scale impact projects with all the due diligence, financial rigor and investment management that one would expect to find in the private sector.

Sir Ronald Cohen, who has been called “the father of British venture capital,” has been leaning into the issue of large-scale impact investments. In his recent book, Impact: Reshaping Capitalism to Drive Real Change, Cohen writes that “[f]or more than 200 years, our existing version of capitalism drove prosperity and lifted billions out of poverty, but it no longer fulfills its promise to deliver widespread economic improvement and social progress. Its negative social and environmental consequences have become so great that we can no longer handle them.” Cohen and a bevy of other former titans of the finance and investment community are beginning to chart out new waters in venture philanthropy that looks to solve some of the planet’s most pressing issues.

Many are beginning to argue that venture philanthropy needs to scale to offer more deals to the global top 0.01 percent, including ones that leverage for-profit vectors as a means for solving issues, institutionalizing philanthropy in a way not unlike how private equity began to take off in the late 1980s.

Historically, wealthy families tend to speak to one set of advisors about investments and asset management and another set of consultants and experts about philanthropy and giving. But these two worlds are beginning to merge—or perhaps collide is a better depiction of what is really happening. Wealth management firms are increasingly exploring the possibility of offering high-return social and ethical giving opportunities to their high net worth family clientele. One example of this type of initiative are the so-called “development impact bonds” engineered and distributed by global banking giant UBS.

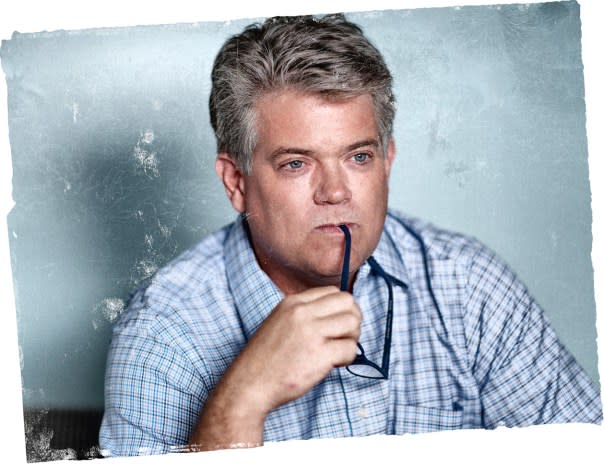

To better understand more about this new approach to large-scale philanthropy, Worth turned to Sean Davis, founder and chief executive officer of Florida-based Merton Capital Partners, which advises ultra-high net worth families around the world on large-scale philanthropic investments to solve specific challenges. Merton is not alone, but it is considered one of the pioneers in creating alternative large-scale giving solutions for families that desire to move the needle on the planet’s most pressing concerns. Davis is the author of a forthcoming Palgrave Macmillan book coming out this fall entitled Solving the Giving Pledge Bottleneck, based on the seminal article he co-authored with the same title which first ran in the Journal of Wealth Management in 2016.

Sean Davis of Merton Capital believes that deploying philanthropy via for-profit investment vehicles is the only way the ultra-wealthy will be able to deploy their philanthropy at scale with the impact they desire. Photo by Sharon Morgenstern Photography

Q: Everyone seems to have their own unique course that brought them into the world of philanthropy. What was yours?

A: I grew up mostly in Cali, Colombia. My dad—an American—was the country manager for Nabisco in Colombia, and my mom is from Argentina. As you might imagine, I grew up in a very privileged lifestyle, but surrounded on a daily basis by very visible signs of poverty and people struggling. After going to boarding school at Exeter, getting my bachelor’s degree at Georgetown and eventually an MBA from London Business School, I found my calling in private equity where I spent a good chunk of my career. Later, I moved into wealth management at Morgan Stanley, and then I became the major gifts director at a non-profit in the homeless space. It was there that I began to fully realize how different the world of private wealth management—particularly on the giving and philanthropy side—was from the world of private equity which I knew so well. I found the non-profit world to be a bit of a parallel universe where there was little to no long-term planning—at least in the way companies approach it in the private sector. I kept on thinking—there’s got to be a better way to do this.

I kept on thinking—there’s got to be a better way to do this.

Do what exactly?

Deploy philanthropy; unlock capital that the global elite would love nothing more than to part ways with—provided it was to an organization capable of making good use of it. It seems kind of crazy to think that it is hard to give away so much money, but executing large-scale giving is hard, but its exactly this type of effort that can move the needle in a way that will make a difference across an array of society’s most pressing challenges.

Are you saying that current models of philanthropy are broken?

At a smaller scale—up to maybe a couple million dollars, it’s working just fine. Or at least as well as it could work without a major overhaul including a shift in both culture as well as the tax code. And for most of the very wealthy households, after a couple of million dollars, that is where they tap out. But what I am referring to is philanthropy at scale. I am talking about the top 5,000 wealthiest Americans and their counterparts across the globe who are looking to have more impact.

You’re saying it’s hard to give away eight- and nine-figure gifts with purpose?

Anyone who says it that it’s easy to deploy a $100 million gift to greatly scale the operations of a non-profit is not being straight with you. You would be hard pressed to find a detailed non-profit growth plan showing how a non-profit can scale over 10 years with $100 million or more. Almost all potential recipients don’t have anywhere near the wherewithal to justify an ask of that size with a compelling investment case, much less have the resources needed to quickly scale. But its these large-scale gifts which are needed now; it’s this type of giving that is going to solve humanity’s most daunting challenges. That’s what we need to fix.

What types of projects are you talking about?

Big ones: clean water, affordable housing and climate change and so on.

What is happening in the world of mega-philanthropy today?

The Giving Pledge is changing the rules of capitalism for those who play the game at the highest level. Some of the most successful titans of capitalism have signalled that solving the world’s problems is a key part—an obligation, if you will—of being uber-successful. Some may say it’s the 21st century version of noblesse oblige or a way of doing tzedakah in a super-charged way. The bold act of taking a public pledge has inspired many, but it has also created a gigantic pool of untapped capital to finance more good.

Davis sees a huge bottleneck in large-scale giving because so few non-profits have detailed plans for geometric growth nor the infrastructure or expertise to deploy mega-gifts.

Photo by Sharon Morgenstern Photography

Would you say the Giving Pledge is a failure?

For me, the Giving Pledge is a movement, not a mechanism. As an advocacy strategy, it has been very successful. It has encouraged other billionaires to commit to give more during their lives or immediately upon their passing. Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffet started a movement that is changing capitalism’s goal—at least a little bit. It has also heralded a new dawn in terms of purposeful impact giving.

Critics often say that a lot of the fanfare about big giving commitments is more about the public relations halo one basks in and the tax incentives than actually driving impact. Where do you fall?

There is some of that for sure. Big gifts that are publicly announced reap PR now, but the tax benefits are only accrued once the gifts are made. But what is really missing is that UHNWIs (ultra-high net worth individuals) are not being presented with giving opportunities commensurate with the funds needed to solve our most pressing social and environmental challenges.

Somehow, many have come to believe that having understaffed and underpaid management teams is the best way to optimize capital deployment in the non-profit world. I’m calling BS on that.

Could you expand on that?

Many of us who are not part of the ‘three comma club’ are still regularly approached by our local schools or any number of small non-profits where we live. These are usually traditional annual gifts or major gifts for their traditional capital campaigns, like funding a new wing at the synagogue, a batch of scholarships for private schools, funding cultural exchanges, buying hospital equipment, etc. But these are not projects requiring mega-gifts to solve the world’s major social and environmental challenges. They are point solutions to very specific, oftentimes local issues.

So, in your view, micro giving will never move the needle on the really big issues?

We have some pretty big issues that need to be addressed now. We need massive change, not slow incremental progress. We can’t let the faucet drip until the bathtub is full. We need to turn the spicket on now. Global water supply. Homelessness and human trafficking. Climate change. Yes, governments are, to varying degrees, attempting to address these issues, but the short-term nature of politics usually gets in the way. Now imagine if you had hundreds of billions of private-sector capital deployed by the top minds in private equity looking to solve some of these issues. It would be a game-changer.

After transitioning to the non-profit world following a career in finance and private equity that took him from J.P. Morgan to Advent International to Morgan Stanley, Davis was shocked to see how different the operating model at major non-profits was from the private sector. Photo by Sharon Morgenstern Photography

Is there a crisis in management talent at non-profits?

I hate to oversimplify and generalize, but for far too long traditional philanthropists have had this mantra of making non-profits pay their managers far less than their private sector counterparts. “It’s about dedication to the mission” they tell themselves. Well, guess what, by crowding out the most talented managers by offering below-market compensation, we are doing a disservice to the capital deployed. If half the MBA class of Harvard Business School went straight into the not-for-profit world, was duly incentivized and stayed there for a number of years, it wouldn’t take long to see some pretty massive innovation across the sector. But the incentives just aren’t there.

Is part of that same problem the issue with ‘program’ or ‘restricted’ giving?

100 percent. We have prevented non-profits from investing in their management, long-term planning and the IT and data systems, in part by asking our gifts to go “straight to the program” or “directly to the beneficiaries they serve.”

Charities pride themselves on being lean, spartan-run organizations, right?

Overhead is a four-letter word in the non-profit world. It shouldn’t be though. We need to invest in competent and incentivized non-profit talent, systems and planning. Not being wasteful is good, but the real question is whether that program is making a difference. Somehow, many have come to believe that having understaffed and underpaid management teams is the best way to optimize capital deployment in the non-profit world. I’m calling BS on that. It’s kind of ridiculous when you step back and think about it. When non-profits are constantly fighting to keep the lights on, developing compelling 10-year plans and getting them in front of Giving Pledge signers is a big lift—impossible for most.For example, a recent study found that only 20 percent of foundations included in their grants the funds to cover the cost of reporting results back to them. Without the funds to manage this, valuable planning time gets chewed up reporting to foundations every year.

So, who is getting it right?

MacKenzie Scott [ex-wife of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos] has taken a hammer to traditional mega-philanthropy. With almost $6 billion gifted across a range of non-profits in 2020, she has made early efforts to not be just another ‘Giving Pledge’ signer unable to meet her pledge. Even so, she is still behind, considering she started at about $35 billion at her divorce in 2019 and is now estimated to have a net worth above $60 billion. She has given hundreds of very large gifts to organizations she never met and with no strings attached after they were recommended by a team of advisors. She’s trusting they’ll continue to do what they do well. It’s trust-based giving at scale.

So having more unrestricted gifts is the key?

Keep in mind that ‘unrestricted’ doesn’t mean ‘slush fund,’ but yes—overly restrictive giving hinders non-profits’ ability to build adequate and competent internal teams to manage, report and adjust programs as needed. The vast majority of mega-gifts are very restricted. Scott has given billions in a short period of time—most of it unrestricted—and that is quite revolutionary.

Overhead is a four-letter word in the non-profit world. It shouldn’t be though. We need to invest in competent and incentivized non-profit talent, systems and planning.

Besides Merton, which other advisory firms are active in this space?

Its growing quickly. Blue Meridian Partners, for example, is doing a fantastic job. It scales non-profits on behalf of its pool of very large philanthropists, such as the Gates, Steve Ballmer, Sergey Brin and others to do the tedious yet necessary work to help build $200 million detailed growth plans for each of the non-profits they help prepare for scale. They select and support competent management teams. Others who do this for philanthropists in different ways include Co-Impact, The Audacious Project, and Lever for Change.

Have any Giving Pledge signers actually met their commitments?

One for sure: Charles Feeney, the co-founder of Duty Free gave away $8 billion quietly and met or even surpassed his Giving Pledge commitment. He gave just about 100 percent of his money away. He used his foundation, Atlantic Philanthropies, to make large traditional gifts after aiming to specifically spend down the foundation and close its doors. The gifts had to be very large and much larger than his annual increase in wealth from his investments.

I know my former boss, Mike Bloomberg, used to joke that his goal is that his check to the undertaker bounces.

(Laughing) Bloomberg has some work to do if he wants to bounce his final check. The reality is that examples of families going the route of Feeney and giving away 99 percent of their wealth before their death will be outliers. The real issue here is that the mega-rich are struggling to even give away 10 percent of their net worth over a 10- to 20-year period.

Tell me about Merton Capital. What does your company do differently?

We are focused on creating alternative vehicles to deploy Giving Pledge funds at scale using for-profits as the main vector.

Using for-profit entities to deploy philanthropy? That’s a twist.

Not really. For-profits can be used to deliver greater impact while taking in all the funds non-profits can’t to deliver solutions at scale. We are creating “philanthropic deals” in capital-intensive industries with leading for-profit companies. These are situations where the philanthropy can be blended into for-profits to deliver impact in their core business, but at a level they can’t reach without the philanthropy.

How can one invest philanthropy into for-profit deals?

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has over $2.5 billion in philanthropy invested into private for-profit companies to develop drugs or other “good” that can’t be generated without the philanthropy add-on. Their Strategic Investment Fund is essentially a portfolio of venture capital investments that happens to be funded with foundation dollars and is focused on attaining high impact by using for-profits as the main vector for reaching these goals.

What about the tax implications of all this?

It takes some structuring but nothing beyond the traditional tax and trust planning that large estates are already regularly engaged in; the IRS allows this. For example, The Rockefeller Foundation, as well as the Ford Foundation, have been doing this for decades using a vehicle called ‘program-related investments’—more commonly known simply as PRI in investment parlance. They see where for-profits can be leveraged to generate impact for philanthropy that can’t be delivered by non-profits.

Mega-philanthropy can empower for-profit ventures to generate more positive impact than they would on their own.

Are these vehicles moving the needle though?

Yes, but not at scale because most of the good being generated with PRI is happening at the venture level. We are talking millions to perhaps tens of millions of dollars deployed through these channels; not the mega dollars we are seeing pent up within the portfolios of the global 0.01 percent. We are simply looking at it from the buyout level, as that is my background. The end-result is the ability to finally move towards measurable solutions to our myriad social and environmental challenges.

Merton is working with UHNW families in the U.S. and overseas who wish to realize a larger, more meaningful and larger scale impact with their giving. Photo by Sharon Morgenstern Photography

How does Merton’s approach work in practice?

We are looking at capital-intensive industries where more capital from philanthropy can generate increases in impact. Since philanthropy doesn’t require an economic return per se, it can act as flexible capital to do more or reduce costs in traditional for-profit projects. We are focused on investing philanthropy in deals where large-scale impact can be measured and delivered in a project, and where we can do the same type of deal over and over. The for-profit vector of delivery increases impact when executed by the same leading private companies and their seasoned management teams. They, in turn, are also happy to generate more impact while making the same profit.

So, in essence the philanthropy deployed through for-profit deals doesn’t subsidize more profits, but rather subsidizes more impact.

Precisely. It allows them to enter areas that are uneconomical without the philanthropy and get deals done.

But how do philanthropists measure impact if its comingled with private-sector dollars. Where’s the line? Where’s the transparency?

We are moving towards measuring against solutions and not just incremental general impact. For example, in our water infrastructure deals, we’re working with the Columbia Water Center and Sciens Water to purchase and upgrade the first of 5,000 utilities that are drastically abandoned, leading to 21 million Americans having polluted water at home. Each one brings clean water to about 10,000 Americans. More deals, more measurable impact. Here, the philanthropy component is opening deal flow and enabling the delivery of massive, solution-based vectors of impact. It’s not subsidizing profits; it’s social justice at scale.

What types of projects is Merton actively working on for clients?

In affordable housing, there are 1,000 tax credit projects getting funded every year on a for-profit basis, built by developers. One deal we have created is using philanthropy to replace bank debt. The philanthropy is structured as a non-interest bearing $10 million loan, which reduces interest expense by say $500,000 per project. These saving can be used to lower rents by that amount permanently, enabling the developer to make the same profit but delivering 300 percent more deeply affordable housing units with the same building. We could do this in 1,000 developments a year with more philanthropic capital added to the funding mix.

It seems that in many cases, the cost of capital is the biggest impediment.

The cost of capital and capital itself. A major part of the solutions to our largest problems are capital-intensive, such as affordable housing, infrastructure upgrades, clean energy generation. Mega-philanthropy can empower for-profit ventures to generate more positive impact than they would on their own, for example by green-lighting large renewable energy projects by lowering costs with philanthropy. The for-profits have management teams that can take in the mega-philanthropy and the track-record to execute in these industries.

Davis sees a new era of private equity inspired philanthropy transforming how capital is deployed using the levers of the for-profit world. Photo by Sharon Morgenstern Photography

What about publicly traded corporations? Is this approach changing how they approach corporate giving?

Corporations are also looking to do more good at scale. Corporate CEOs and their boards are quicker in reacting to calls for ESG improvements, DEI and social justice, etc. Corporations are all looking to invest in solutions to address our biggest challenges, as ESG ratings start to quantify impact scale and scale of good will influence market capitalizations. I expect to see more public-benefit and B-Corp conversions too as that practice gains steam.

There’s tremendous pent-up wealth wanting to finance more good.

Furthermore, affluent millennials and Gen Zers—the children of multimillionaires and billionaires—are pushing their family offices to invest their portfolios in companies with high ESG ratings. As a result, banks and public companies have gotten the message and have never been so incentivized to invest in good. They are looking at their supply chain, hiring practices and the diversity of their board rooms; they don’t want to be left on the side lines.

And how are traditional foundations reacting to these changes?

Foundations are looking for ways to rethink their approach and explore spending larger amounts of their endowments. There is an increasingly louder call for foundations to spend down their endowments, and this call has become louder since the onset of COVID. A few foundations, like Kellogg, Ford and MacArthur, borrowed against their endowments to increase their COVID-related emergency giving. Some other ones like Edna McConnell and Atlantic Philanthropies are spending down or have spent all their funds. Although this is not a new idea, it is accelerating now, and it’s happening in tandem with calls to pass legislation to force minimum giving standards on donor-advised funds. More philanthropy is coming.

Davis sees a continuing increase in the flow of philanthropy for larger-scale projects. His firm has developed various strategies to align donors with private companies, unlocking large-scale impact for philanthropists and private industry alike. Photo by Sharon Morgenstern Photography

Final thoughts?

More funds need to be gifted. I believe that the more we can leverage for-profits, which want to do more business, and do more good, the more scale we can achieve. It is also the way to deploy the other 95 percent of The Giving Pledge and beyond. Remember, the signers of The Giving Pledge represent less than 10 percent of the world’s billionaires. There’s tremendous pent-up wealth wanting to finance more good. There has never been an opportunity to finance more good than right now.

The post Reimagining Large-Scale Impact Philanthropy: An Interview With Merton Capital Founder Sean Davis appeared first on Worth.