Red voters for green energy? Conservatives say they support solar and wind power too

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

During the Cold War, John Lehman served as Secretary of the Navy under President Ronald Reagan. Later, he was appointed a Republican member of the 9/11 commission.

Those experiences led him to see U.S. reliance on “Persian Gulf oil” as a major vulnerability that kept America mired in Middle East conflicts.

Lehman became a champion for renewable energy — "an essential element of energy independence,” he said. He lobbied for it during Congressional hearings, and at his rural estate in Pennsylvania, where a peacock and guinea fowl run the grounds, he installed a 34-kilowatt solar array to provide most of the power he needs.

“It seemed to me, here I was arguing for renewable sources … and I’m not doing anything,” Lehman said. “So I ought to at least get a solar array.”

Lehman's embrace of renewables makes him a figure often overlooked in American politics, where conventional wisdom suggests liberals are more supportive of solar and wind energy than their conservative counterparts.

Indeed, Democratic politicians have delivered the nation's most significant climate policies to date. In 2014, the Obama administration introduced the Clean Power Plan to reduce carbon emissions from the energy sector; the Trump administration worked to rescind it. Under President Joe Biden, Democrats have sought to invest hundreds of billions of dollars into climate-focused projects; Republicans have largely opposed the spending.

And yet, national polling shows the majority of self-identified conservative Americans also want a future with less burning of fossil fuels, replaced by renewable energy. Conservative interest groups have started a state-by-state campaign to convince the party's base and leadership of the virtues of solar energy.

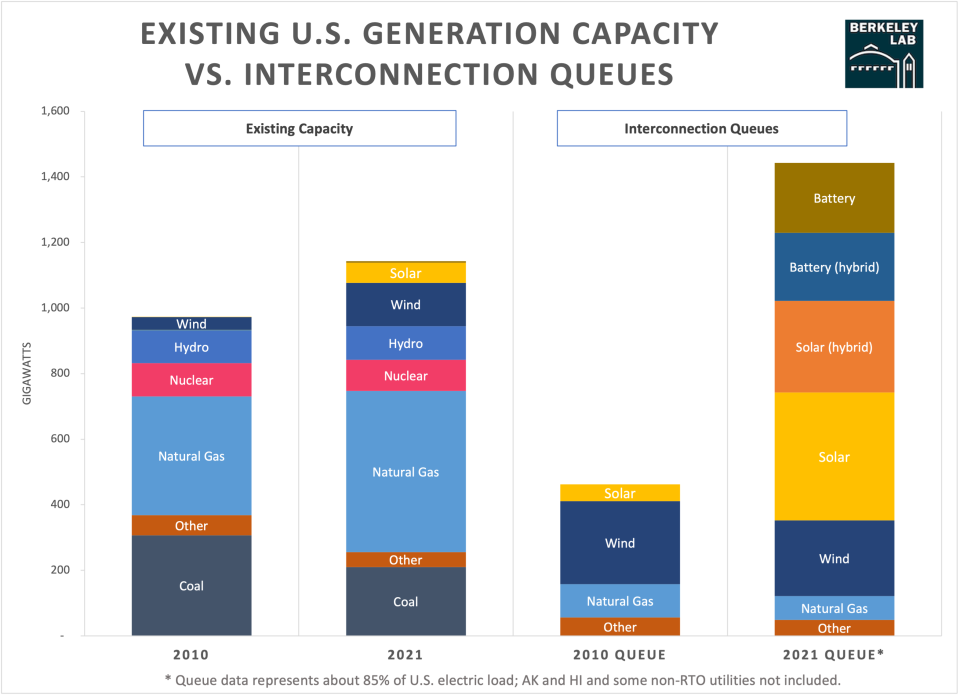

And big money from both new start-ups and traditional oil and gas companies are lining up behind renewable energy development projects across the country, with enough planned to theoretically push U.S. energy generation to more than 80% renewable, according to Joe Rand, a senior engineering associate with the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“There’s more capacity in the queue than we have existing power plants in the U.S.,” Rand said. “It’s an almost 100% transition of the electric system.”

But formidable obstacles remain. A bipartisan appetite for a swifter transition to renewable energy faces both bureaucratic and political bottlenecks, advocates say.

Lodged in the gears are traditional pet peeves for both parties. Aging infrastructure and understaffed regulatory agencies are hampering the development of renewable energy, Democrats say.

But a mishmash of regulatory and legal systems, often used by environmental advocates to stall and kill oil and gas proposals, can also now waylay renewable energy projects, conservative advocates counter. They argue that zoning restrictions and laws like the Endangered Species Act are being used to oppose renewable energy projects, when concerns are actually based on aesthetics or property values.

Even as a rapid drop in the cost of technologies like solar panels makes renewable energy financially enticing, such regulations are holding back how quickly they can be built, conservative advocates argue.

“There’s a great need for certainty,” said Ned Rauch-Mannino, an energy consultant and former deputy assistant secretary for the U.S. Department of Commerce under the Trump administration. “It threatens projects whether they’re traditional or renewable.”

Advocates worry about a closing window of opportunity. Democrats fear their chances to promote renewable energy legislation could be threatened by the midterm elections. In Republican circles, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and inflation appear to be increasing the appetite for further oil and gas development, risking a turn away from wind and solar.

And time is running out globally, as the planet pushes toward a warmer and more dangerous future. If there is a road to agreement on a swifter energy transition to stave off the worst possible outcomes, the time is now, said Joshua Busby, a public affairs researcher and energy policy expert at the University of Texas

“The situation is not going to get any easier in the next Congress,” Busby said. “Do we want to seize the future for the country's benefit or not?”

Red-on-red war

Republicans dominate in western Pennsylvania's North Beaver township, where 73% of voters cast their ballot for Donald Trump in 2020. But lately there's another battle brewing there, pitting conservatives against conservatives.

This time, it's over solar panels.

In recent years, Vesper Energy, a Texas-based solar developer, has pitched farmers in North Beaver on leasing their land for solar arrays. The company hopes to stitch together thousands of acres to build out 200 megawatts of solar energy — enough to power 38,000 homes a year, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association.

The proposal has received significant pushback among some residents, who flooded township meetings with concerns that large solar arrays would drive down the availability of farmable land and detract from the community's rural character.

“I wouldn’t want to come out of my house in the morning and look left and right and see all solar,” Don Hoye, a board member with the Lawrence County conservation district, told the local New Castle News.

For now, opponents are winning. Last year, the township passed a ban on solar arrays on farms that sell back to the grid.

But other conservatives are fighting back, and seeking to ally with prominent Democratic politicians.

Herm Cvetan, a farmer in North Beaver who wants to build solar on his property, sees installing solar as an extension of his rights as a landowner. He said farms have long harnessed renewable energy like wind and water to mill grain and believes solar will help farmers secure their bottom line and land.

“If banning solar is OK, farmers will have no choice but to sell prime farmland to home builders when hard times take their toll,” Cvetan wrote in an email.

The battle in North Beaver also caught the attention of Chad Forcey, executive director of the Pennsylvania Conservative Energy Forum, a group advocating for renewable energy in Republican circles in the state. Last year, Forcey and his staff began attending township meetings in North Beaver, arguing the case for rescinding the ordinance.

When that failed, Cvetan and Forcey filed a complaint in March with Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, a Democrat who is running for governor. The complaint alleges the ordinance is in violation of several laws, including the state's constitution, which guarantees “a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation” of the environment.

Forcey sees it as an important moment: Will a powerful Democrat align with conservatives for renewables?

Asked about the complaint, Shapiro's office told USA TODAY that it would be “premature for us to comment at this time.”

The conservative push for solar extends beyond Pennsylvania.

Forcey's group is part of the Conservative Energy Network, a Michigan-based organization started in 2016 by Mark Pischea, a Republican strategist in that state. The network supports organizations like Forcey’s in 23 states, more than half of which voted for Donald Trump in both 2016 and 2020.

Forcey said the groups have a two-part mission: increase grassroots support for renewable energy among conservatives, and work with state politicians on crafting favorable laws, particularly those allowing freedom for residents and businesses to install solar as they please.

Data show the groups are working with a receptive audience.

In 2020, researchers Matthew Nowlin and Rachel Hawes at the College of Charleston in South Carolina asked 1,300 Americans what percentage of everyday electricity they thought should come from renewable sources, and how much from traditional oil and gas.

Those who identified as liberal Democrats wanted the greatest amount of transition: a nearly 40% reduction in the use of fossil fuels, and a 38% increase in renewables. But conservative Republicans also wanted fossil fuel use reduced, by 29%, with renewables increased by 23%.

“That doesn't break down as cleanly into partisan camps as we might think,” Nowlin said.

The results also line up with prior research conducted by Nowlin’s team and others. Studies show conservatives often don't think of renewable energy technologies as climate solutions; instead, they prefer them for economic, self-sufficiency, or security purposes. Young conservatives are also more likely than their older counterparts to accept the scientific consensus on global warming, leading them to also want more renewables.

The dynamics have led to similar rates of adoption of renewable technologies like solar across America's political divide, according to research from the University of California at Santa Barbara.

“Republicans are just as likely to put up solar panels as Democrats,” Nowlin said.

Gridlock slows hot market for renewables

Outside the political realm, experts say market forces are driving a big push to develop commercial-scale wind and solar projects.

Rand, with the Department of Energy, closely tracks new power plant proposals submitted to a complex network of electric grid operators across the country. These agencies serve as the primary clearinghouses for new energy generation proposals, ensuring projects are legitimate and can smoothly integrate into the vast network of power lines providing energy to homes and businesses.

Renewable power applications have seen rapid growth since 2006, with wind initially leading the way, but solar now rocketing in market share as the cost of panels drops. On their best days, states that invested early, like California, are achieving nearly 100% energy generation from renewable sources.

But the rapid growth of wind farms in states where Republicans dominate, like Texas, Iowa, and Oklahoma, are also boosting a nationwide energy profile that saw the U.S. achieve one-fifth of its energy needs from renewable sources in April, a new record, according to Ember, a climate and energy think tank.

Many energy companies are coming to prefer the economics of renewables, Rand said. Solar and wind projects have predictable upfront costs and dependable payoffs, compared with the boom-and-bust cycles that often define oil and gas.

“You have a really hard time predicting the volatility of the price of natural gas,” Rand said. “A lot of people are viewing wind and solar as a hedge against volatility.”

The demand for renewables is so great that more than 90% of energy project proposals now before grid operators are for wind and solar. Theoretically, if every project proposed was approved, there would be enough renewable energy to meet 80% of U.S. demand by 2030, calculations from the Department of Energy show.

But there’s another statistic that curbs Rand’s enthusiasm: 16%.

That's the chance a proposed solar project will ever actually see the light of day. The other 84% never make it past blueprint. Wind fares just slightly better, with a 20% success rate.

Project queues for grid operators have backed up in recent years, and they’re not clearing applications like they used to, Department of Energy figures show. From 2000 to 2010, companies averaged about two years from the proposal of a new power project to its approval and operation. Now, the figure is closer to four years.

Rand said energy companies have grown frustrated with grid operators, which they believe are moving too slowly in reviewing applications. But grid operators in turn complain about the influx of new project proposals from companies, which they say will often submit three or four applications, when they have intentions of building only one or two. The number of applications rose from about 1,000 in 2015, to 2,000 in 2019, up to more than 3,000 in 2021.

“When we talk to the developers ... they say it's the grid operators, that they're doing things wrong,” Rand said. “Then when we talk to those grid operators, they blame the developers.”

But that's just one of several roadblocks.

When new power sources come online, they require proper infrastructure: high voltage power lines that can carry the energy to regional or even national markets. But in many places that infrastructure is old or doesn't exist, creating a question of who will pay to build it, often falling to developers.

“Many perceive that as unfair,” Rand said. “It kills the project in many cases.”

There is some promise. The $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill passed last year contained about $65 billion to build up the nation's transmission lines, which the Biden administration called “the largest investment in clean energy transmission and grid in American history.” This week, the Biden administration also announced an executive order invoking the Defense Production Act to try and spur domestic production of solar panels and “transformers and critical grid components.”

But Ronald Fisher, executive director of The Energy Co-op, which provides 100% renewable energy to residential customers in southeast Pennsylvania, believes there's a bigger problem: too little policy coordination among state governments, grid operators, and federal agencies, each of which can influence renewable energy.

While demand for wind energy is high in the co-op’s market, Fisher said "nobody is building" there. Pennsylvania has not made the same climate commitments as neighboring New Jersey, where requirements to generate wind power in state and development partnerships with New York and the federal government have led to burgeoning plans for offshore wind power development.

Meanwhile, the grid operator that serves Pennsylvania and 12 other states, PJM, has proposed a two-year freeze on new energy applications as it works through a backlog. And the cost for all electricity in Pennsylvania is dependent on that of natural gas, meaning rates are rising for Fisher's customers even though they use wind and solar.

Instead of this fragmented system, Fisher would like to see the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission follow through on a recent push to develop a nationwide plan to upgrade the grid and promote an energy transition. That would pair new funding for infrastructure with a holistic plan to use it effectively.

“Currently, it's a cacophony of interests,” Fisher said. “The single biggest hurdle is the lack of central planning.”

While many conservatives are skeptical of federal intervention, others say they can get on board with the government playing a larger role in some cases. Forcey said his organization can support tax breaks and other financial incentives to help grease the path for renewables. They would also be comfortable seeing an increase in funding for grid operators, in order to beef up staff and more quickly review projects.

But they also want concessions from Democrats, such as agreeing to tighter deadlines for regulatory agencies, limiting state and local development restrictions, and cutting other red tape, particularly by reworking environmental regulations that can delay reviews and send proposals to the courts.

Lehman, the former Navy secretary, holds out hope that agreements can be reached. When he converses with Democrats about renewable energy at national security conferences, he said partisanship falls away.

"There is no red and blue," Lehman said. "It's totally bipartisan."

Busby, the University of Texas researcher, is skeptical. Renewable energy policies so far under the Biden administration have fallen short from what his research calculated was politically feasible in 2020. The Senate in particular, where voting margins are razor thin, has proved a stumbling block.

The U.S., Busby says, is losing precious time not only on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but catching up to countries like China that are investing heavily in renewables.

“I hope that the senators will find a way to take advantage of this moment,” Busby said. “It’s not simply about climate change. It’s about the economic future of the country.”

Kyle Bagenstose covers climate change, water and other environmental topics for USA TODAY. He can be reached at kbagenstose@gannett.com or on Twitter @kylebagenstose.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Many Republicans also want more solar power but deals may be elusive