Reading reforms in Mississippi have improved scores. Are there lessons to learn about how to better teach our children?

JACKSON, Miss. - Waving a yardstick in the air to get everyone's attention, Sophelia Sykes began a review with her kindergarten students.

“Letters and sounds now,” Sykes said, adding with a smile, “I’m looking to see if your lips are moving.”

A chorus of singsong voices responded.

“Q, queen, quh,” the Spann Elementary students chanted. “R, rat, ruh. S, snake, suh.”

Pairing letters and sounds with words might seem basic. But when Sykes first started at Spann 15 years ago, such drills were not a part of the lesson plan.

“Children can sing the alphabet by the time they’re two or three years old, but it has no meaning if they can’t associate the letters they’re saying with an actual word,” Sykes said.

This greater emphasis on phonics-based instruction — using the sounds of letters, and combinations of letters, to figure out words — is part of statewide reforms that have dramatically improved reading levels in Mississippi. The reforms, especially coming from a state typically not seen as an innovator, have captured the attention of educators and politicians across the country.

For the first time, Mississippi led the nation for gains on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Known as the Nation's Report Card, it measures how students perform in mathematics and reading.

In Mississippi, the percentage of students who performed at or above the proficient level in reading was 32% in 2019. That's higher than the previous testing period — 27% in 2017 — and much higher than a generation ago, in 1998, when it was 17%. The state met the national average, something it had never done before, boosting its ranking to 29th. Not that long ago, in 2013, it had been nearly dead last — 49th.

Wisconsin, on the other hand, has barely moved the needle on NAEP scores in 30 years. The percentage of students who performed at or above the proficient level in reading was 36% in 2019, 35% in 2017 and 34% in 1998. While Wisconsin's numbers remain higher than Mississippi's, the trend line is flat.

Further, Black fourth-graders in Mississippi are outperforming Black fourth-graders in Wisconsin in reading, portending what's to come in other academic measurements as the students age. And while Black students in Mississippi averaged a reading score 21 percentage points lower than White students — nothing to be content with — the performance gap was 39 points in Wisconsin, a chasm that is both shocking and familiar.

“We have done virtually nothing to close the Black-white gap,” said state Rep. LaKeshia Myers, a Milwaukee Democrat.

Nationally, a just-released NAEP report, the first to gauge the impact of the COVID pandemic, shows a national drop in scores. State by state results will come later. Still, while far from perfect, Mississippi appears to offer lessons on how reading improvements can be achieved.

Its jump in reading scores has been attributed largely to the passage of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act in 2013. The Act emphasized grade-level reading skills, particularly as students' progress from kindergarten through 3rd grade. It included statewide training for teachers based on the science of reading; literacy coaches to provide support for teachers in the classroom; and specific intervention services for students who struggle.

The Act also made a promise: Students at the lowest achievement level in reading on the statewide assessment for 3rd grade would not be moved on to 4th grade. It got even more teeth in 2016, when it was amended to include individual reading plans for those who need them, and increased expectations for all 3rd graders.

Katie Kasubaski, the state leader of Decoding Dyslexia Wisconsin, said she considers Mississippi a model of how key leaders can come together around a shared vision to improve reading.

“They were all on the same page ready to make those big changes,” Kasubaski said.

Lingering effect of the 'reading wars'

Wisconsin has not had such a united front.

Efforts to enact some of the same reforms as those in Mississippi have met considerable opposition, particularly from the Wisconsin Education Association Council — the teachers union.

In November, Gov. Tony Evers — a former educator who draws political support from the union — vetoed a Senate bill that would have tripled the number of literacy tests young children take in school, citing insufficient funding and lack of evidence that it would work.

In April, the governor vetoed a bill that would have mandated personal literacy plans for students with low reading assessment scores, for the same reasons.

“Every time the word ‘education’ comes up, it’s like spidey senses go off,” said Myers, the state representative from Milwaukee. “It conjures up all these bad memories of debates.”

Those debates, sometimes called the “reading wars,” raged long before Evers came into office, and extended far beyond Wisconsin.

Broadly, phonics involves sounding out words, whereas what's known as the "whole language" approach emphasizes reading for meaning and figuring out words by their context. Advocates of phonics contend it helps students who aren't exposed to much reading at home, and those who are dyslexic; opponents suggest it is too drill-oriented and doesn't develop comprehension and a love of reading.

Today, phonics is generally accepted as necessary — it's the degree of "necessary" that continues to be contentious.

More than a decade ago in Wisconsin, a nominally bipartisan “Read to Lead" task force was convened to address best practices in educating schoolchildren. It was perhaps the most prominent of multiple efforts to bridge the entrenched divides over reading. The task force included educators, reading experts, elected officials from both parties, and philanthropic and nonprofit representatives.

Among the recommendations: require teachers to undergo rigorous reading testing before they are licensed, and screen kindergarteners to catch problems early on and provide them needed support.

To this day, almost none of the recommendations of the task force have materialized.

Teachers receive training, mentoring

In Mississippi, providing support for teachers under the literacy law has involved complementary efforts: professional development and literacy coaches.

“These were two components of the law that went into effect pretty much immediately,” said Kelly Butler, CEO of the Barksdale Reading Institute, which works to improve reading in Mississippi’s public schools.

Every school district in Mississippi enrolled their teachers in the Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) — an online program that provides K-12 educators and administrators with the skills they need to teach phonics. Funding came directly from the Literacy-Based Promotion Act.

But if teachers simply soak up the content, only about 15% of the material is ever implemented in the classroom, Butler said. That is where coaching comes in.

“When you introduce coaching, (the material implemented) goes up to about 95 percent,” Butler said.

In Mississippi, finding qualified literacy coaches was challenging.

“We had to train all the coaches, too,” Butler said. “In the first year we passed the law, we had 500 applicants for what we were hoping were 75 spots, and we barely filled 25 spots. That’s how thin the pool of people was.”

Today, there are about 80 trained coaches that work across the state, about half in Jackson Public Schools, the second largest and only urban district in the state, serving more than 12,000 students.

“When we provide professional learning development, our coaches are in schools the very next day or week to … see what that looks like in classrooms,” Crain said.

Teamwork is crucial, especially for veteran teachers who may have learned a different way of teaching reading, said Delane Lesh, assistant principal of Spann Elementary.

“To be a good teacher, you have to read, research and see the best practices out there that others are using and you can implement,” Lesh said.

One teacher who has been at Spann for nine years said that when she started, if kindergarteners "just knew their alphabets and some sounds, it was good enough.”

Now, it is as though kindergarten is first grade.

“They’re requiring more of the students and of us,” she said.

Building the plane 'as we're flying it'

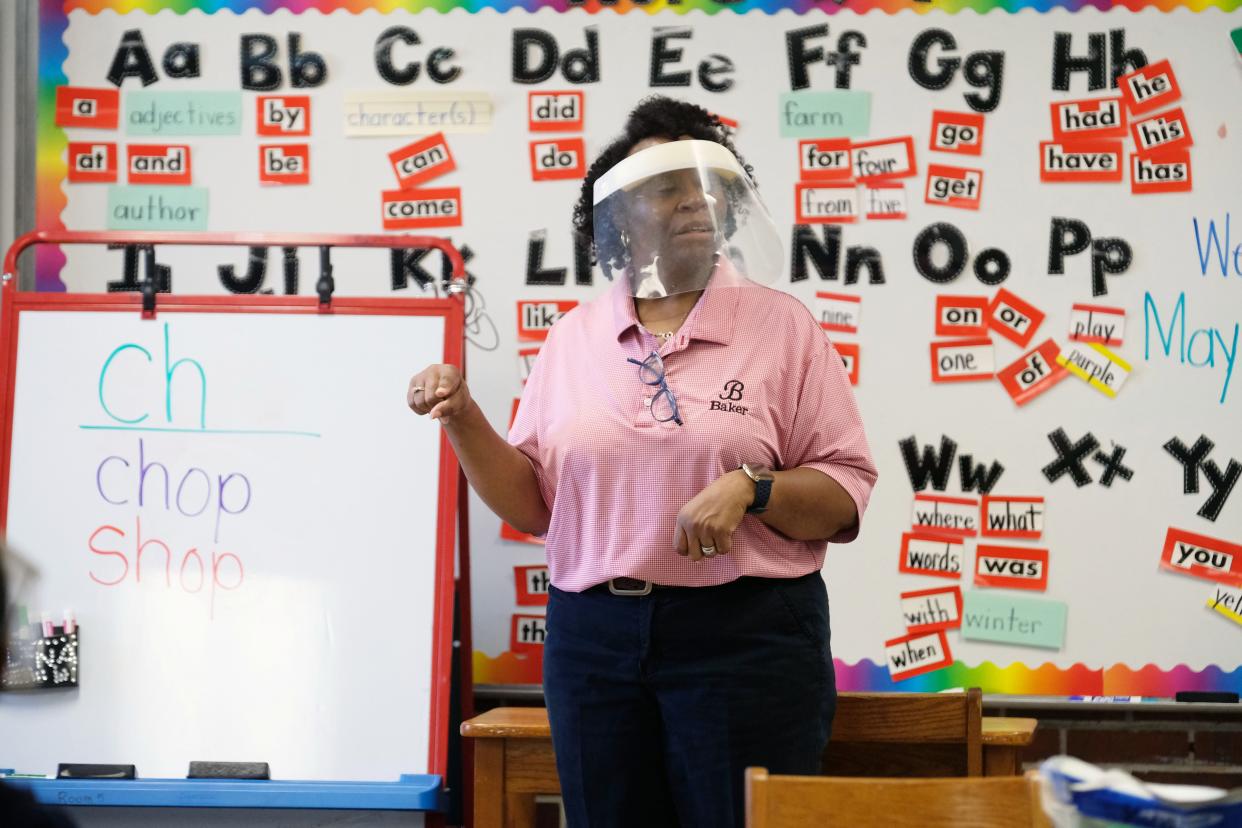

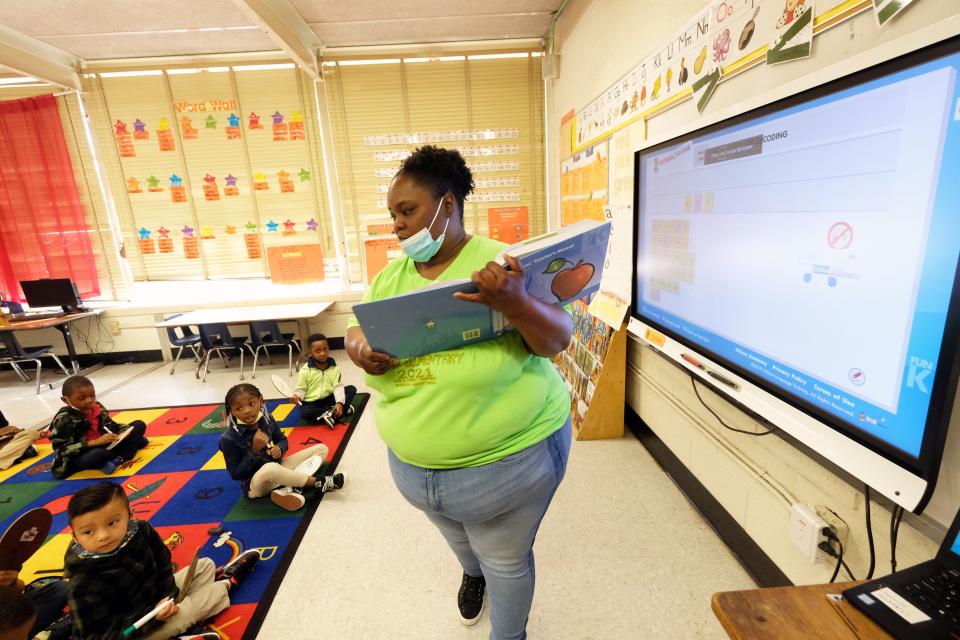

On a warm Friday at Baker Elementary School in Jackson, a gaggle of pre-kindergarten students read out morning announcements, their voices filling the red-and-white halls.

They close the announcements with the Baker creed: “I will listen. I will think. I will read. I will write.”

Camesha Hatchett has led the school of about 250 pre-kindergarten-through-5th grade students since 2019. All are economically disadvantaged; 97% are children of color. Lifting them up to their full potential is the driving idea behind the Literacy-Based Promotion Act.

“It’s been a lot of work,” said Kelly Crain, assistant state literacy coordinator. Even with the parameters set down by the literacy act, “We say we’re building the plane as we’re flying it.”

After the act passed, Jackson Public Schools bought two English language arts curriculums: “Wit & Wisdom” and “Wilson Fundations.” Both teaching programs were created with science behind them, specifically research from linguists and psychologists on how the brain processes language.

The curriculums are reliant on using phonics both in texts and group discussions to improve reading fluency. For example, during a 30-minute Fundations lesson in a kindergarten class at Baker, the students were going through a lesson with a story about Fred the Frog.

First came decoding — the process of reading words in the text.

“There’s an adjective here, which describes something,” the teacher said. “How did he jump?”

“Quick!” responded the children.

“So Fred jumped over the twig, on the grass and over the moon,” the teacher continued, as the students repeated after her. “And now we have a trick word: dogs. What’s tricky about that?”

“It has the suffix 's’ at the end,” one girl said. “That means we’re talking about two or more!”

Next came encoding — the process of using letter-sound knowledge to write words.

Students tapped out sounds with their fingers, then wrote on their whiteboards to identify the long vowel sound in the word “go,” a digraph “ch” in the word “chunk,” and a blend “st” in the word “stop.”

“This is the application of the science of reading,” Crain said. “She’s not asking them to guess or skip a word. When they get to a word they don’t know, they use the skills learned in Fundations to say the sounds and get the word.”

As more states make the science of reading a policy priority, many are designed with these methods in mind.

Former Gov. Phil Bryant of Mississippi, who himself is dyslexic, was a key player in the 2013 changes. A Republican, he had the support of the conservative majority of the state Legislature.

“The concern was that too many kids were getting well into middle and high school, and still struggling to read,” said Butler, of the Barksdale Reading Institute.

Intervening with struggling students

Despite Mississippi's improvements, the rising tide does not lift all boats. Some students still struggle to read.

So with the 2013 literacy act, there is also a focus on intervening with struggling students immediately, or holding back those who could not pass the third-grade assessment. Labeled a “retention law,” it was some time before this part of the act gained bipartisan support. It gave the impression students would be held back en masse, or that particular communities of children would be singled out. By including a “good cause exemption” to ensure that special education students were not unjustly penalized by benchmark testing standards, it gained support.

“Many of my colleagues and allies who associate themselves with the Democratic Party were in favor of this, provided it did not put the burden totally on nine-year-olds,” Butler said.

Kindergarten-through-3rd grade students are now screened for reading proficiency three times a year. There are six approved screening tests in the state of Mississippi, down from a mishmash of 117 tests when the act was first passed.

When students test poorly, parents or guardians are notified and individual reading plans can be created. Specialized instruction is then provided.

At Spann, "intervention time" was implemented to help struggling third-grade students get ready for testing. The idea is not to single them out, but to give them needed time to get one-on-one assistance with so-called "interventionists," who may be retired teachers or other support specialists.

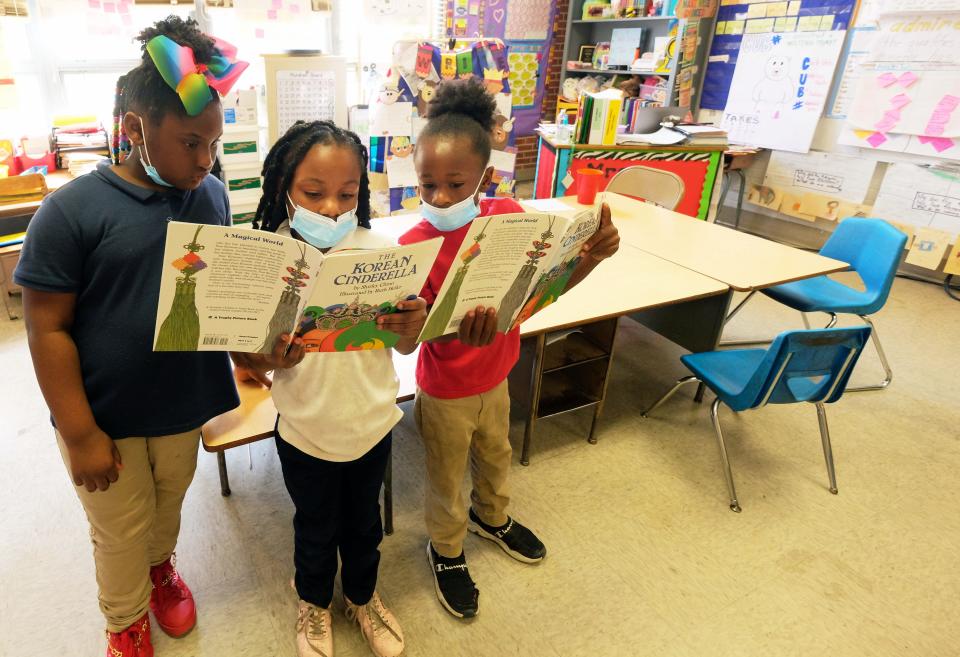

During one recent "intervention time," students were given a passage to read and then a list of questions about it. They were instructed to highlight any textual evidence they found to support their answer.

“You’ve got your thinking cap on?” the interventionist asked. “I left it at home,” one boy responded.

Barksdale is working with the state to develop a pathway to get intervention that follows the students into higher grades.

“We’ve so long been the underdogs, the impetus was on us to change,” one interventionist said. “There’s nowhere to go but up.”

Not on the same page

Wisconsin has had little success getting off the ground, much less going up.

The state has a dire need for teachers; the University of Wisconsin-Madison even pays for tuition and fees for teacher education students who agree to work in the state for several years. But there's little agreement on what qualifies a teacher to impart reading to youngsters.

In 2014, a Fundamentals of Reading Test was created for people applying for teaching licenses in Wisconsin — one of the key recommendations from the old Read to Lead task force. The premise: It's impossible to teach reading if someone isn't particularly good at it themselves.

But the test has skeptics.

“One high-stakes test does not determine competency,” said Myers, who is a proponent of allowing educators to submit a portfolio rather than one be-all and end-all exam.

Further, a loophole makes the exam not nearly as high-stakes as it seems, said Chan Stroman, an attorney and phonics-based instruction advocate based in Madison.

“As soon as the (FoRT) was enacted in 2014, there was immediate and successful activity (by the teachers union) to undercut that requirement,” Stroman said. “Now any teacher can become licensed on an emergency license — the equivalent of a temporary license that gets renewed every year.”

Even with the loophole, the shortage of qualified teachers remains.

“There simply aren't enough expert teachers to meet the needs of all of the kids who have difficulty with learning to read,” said Debra Zarling, president of the Wisconsin State Reading Association.

What gets taught to teachers even before they try for a license is another issue. In schools of education — where future teachers are trained — some instructors fully support explicit phonics instruction, others still lean toward the whole language approach, or treat them equally.

“Teaching more phonics, which is one of the things that's often being promoted, doesn’t result in better readers,” Zarling contends. “I believe it definitely needs to be taught. But the teacher also needs to be able to adjust it based on the needs of their kids.”

That's anathema to educators who are all-in on phonics. And in fact, Wisconsin’s Department of Public Instruction endorsed “explicit and systematic phonics instruction” in 2020.

Beyond that, once in the classroom, Wisconsin requires teachers to have access to a qualified literacy specialist to help them. But although it is in the books, that does not mean it is being followed, Zarling said.

“Many districts just put a name on the line when they're asked if that person has the qualifications, but they don't necessarily act in that capacity,” Zarling said.

It's the law, but is it followed?

Another proposal from the Read to Lead task force was screening for reading readiness.

Under current law, schools must assess students annually from pre-kindergarten to second grade using a three-tiered early literacy screening program. Typical of the schism in Wisconsin, the state branches of Decoding Dyslexia and the International Dyslexia Association were in favor of the law; the state reading association was against it.

“We don't have a problem identifying kids who have struggles, what we have is a problem providing the support that they need,” Zarling said.

It is unclear how many school districts follow the law and intervene with students who need it.

“It is certainly clear that the DPI has no interest in monitoring it,” Stroman said. “DPI is not catching students who are at risk of reading failure and basically telling parents to wait to fail.”

Wisconsin is in the minority of states that still does not require screening or intervention for dyslexia. There is also no requirement in Wisconsin that parents be notified about such intervention.

“My daughter was getting actual intervention and we were told she was just getting extra help,” said Katie Kasubaski, leader of Decoding Dyslexia Wisconsin. The family was not part of the process.

Even in Mississippi, doubts linger

For all the progress in Mississippi, there are still challenges — and people who wonder if the gains are a mirage.

Spann Elementary went from an "F" to a "B" on the state's report card since the literacy act went into effect. But it's not the norm.

“Going from an F to a B (is uncommon) in Jackson,” one interventionist said. “Jackson is really struggling.”

That's true for schools and students. Despite trying to catch lagging students early, Mississippi has a higher retention rate — not advancing kids to the next grade — than any other state, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education.

In 2018-19, 8% of all K-3 students in Mississippi were held back, up from just over 6% the previous year. The pandemic put a pause on this, meaning that third graders in Mississippi during 2020-21 that failed the benchmark test would not be held back.

The retention rate is a point of contention in Mississippi — even though it was a key promise of the literacy act legislation. Parents are concerned because grade retention is correlated with negative outcomes of education, such as dropping out as they age through the system. And with a high rate of turnover among Mississippi’s teachers and students, there are still not enough trained staff to work with the children who need help.

Ginny Strauf from Meridian, Miss., whose daughter is dyslexic, chose to homeschool rather than leave her daughter without a path forward.

“They said there was nothing they could do with her,” Strauf said. “At that point, I pulled her out. I don’t see the schools getting any better.”

After a few months, she thought about re-enrolling her daughter in school, and during that time, teachers told Strauf that because her student had an individualized education plan, she would not need to take the third grade benchmark test.

In other words, due to a "good cause" exemption, her daughter would not be counted in the state's data. Strauf now believes that Mississippi's celebrated gains may lack context.

“Only good readers take the test,” Strauf said.

Lelah Byron produced this story while serving as a research assistant to Sarah Carr during Carr's 2021-22 O'Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication. Marquette University and administrators of the program played no role in the reporting, editing or presentation of this story. Carr, a former Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter who is now an independent journalist, contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Could Wisconsin educators learn from Mississippi's reading reforms?