‘We have to put our foot down’: Florida wildlife managers ban invasive reptiles

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission on Thursday signed off on banning the sale, ownership and breeding of tegus, iguanas and other invasive reptiles that have overrun native wildlife populations.

Many of the new rules — approved in a unanimous vote over pushback from reptile breeders and sellers — will be phased in over coming months to give businesses time to comply. The toughest measure — a total ban on commercial breeding in Florida of tegus, iguanas and prohibited snakes — won’t go into effect until June 2024. Pet owners will have 180 days to comply with new regulations mandating concrete enclosures for reptiles kept outdoors.

The rules represent the strictest crackdown from Florida wildlife managers yet on an exotic pet trade that scientists blame for the state’s worsening problem with invasive reptiles. The infamous Burmese python, which has largely wiped out small mammal population in the Everglades, is only one of many invasive species that pose a high risk of spreading across subtropical South Florida. Its sale and import in the state was blocked in 2010.

“We have to put our foot down. People want to move to Florida because of nature, because of our environment. The time has come to take a bold stand against these real threats to our environment,” said Rodney Barreto, FWC’s newly elected chairman.

In a board meeting on Thursday wildlife managers placed on FWC’s prohibited list all species of tegu lizards and the green iguana, as well as green anacondas, Nile monitor lizards and six species of pythons. Some species were previously on the conditional species list, which meant that breeding was allowed with permits. Now, tegus and iguanas are in the same category as pythons and Nile monitor lizards, which cannot be sold as pets. The rules also ban importation of these species.

After more than 5,500 survey responses and 4,000 written comments, FWC made some changes to the rules that were originally proposed last July. The agency expanded possession allowances for licensed trappers and let current tegu and green iguana pet owners keep their animals with a no-cost permit. Breeders and pet owners will have 180 days to comply with the new regulation after commissioners agreed to more time than the 90 days originally proposed.

FWC is targeting the exotic pet trade because most invasive fish and wildlife in Florida were established through the escape or intentional release of captive animals. They say there is evidence the 16 targeted species in the new legislation already have local populations or may become established and negatively impact Florida’s ecology, economy or human health and safety.

Another invasive spreads in Florida: A red-headed lizard with an appetite for butterflies

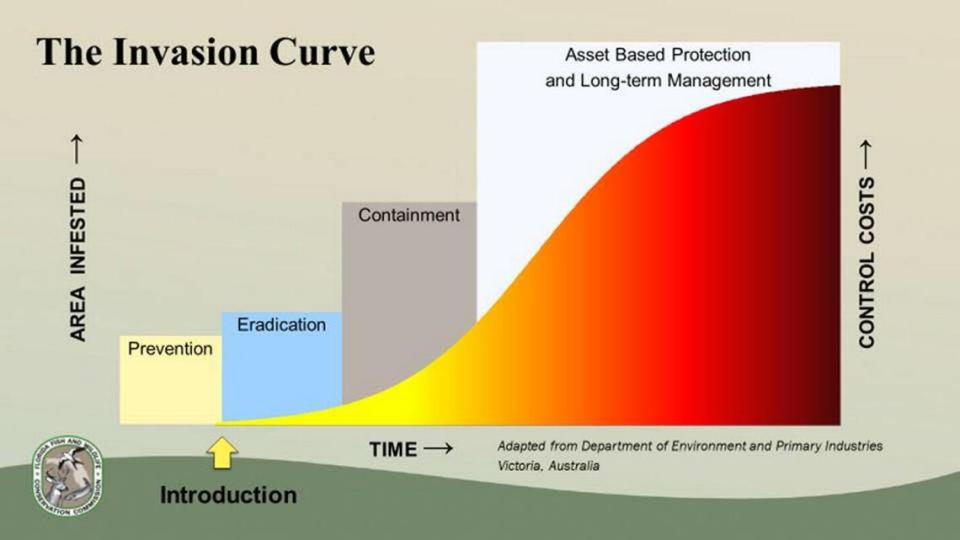

FWC said the exotic species pose a significant threat to Florida’s fragile ecosystems like the Everglades, and that current regulations are no longer effective in managing their expansion and damage. With more than $10 million spent annually on invasive species, joint efforts by FWC and other state and federal agencies are nowhere near controlling some of the more widespread invaders.

“The global movement of products and people, the increased demand in the global market for exotic animals and the ease to acquire them has increased the potential for non-native fish and wildlife to escape or be released and ultimately cause impacts. Invasive fish and wildlife are considered the second most significant threat to biodiversity, after habitat loss,” FWC said in a presentation during the meeting.

Reptile breeders and pet owners said the new regulation is unfair, not based on science and ineffective in addressing the problem caused by invasive reptiles that are already established.

“The proposed rules are far from reasonable and they won’t help resolve the problem the state has with invasive species,” said Phil Goss, president of the national U.S. Association of Reptile Keepers. He said the new regulation targets breeders and enthusiasts who are responsible reptile owners.

Ariel Collins, an economist who spoke against the rules, said FWC’s Statement of Estimated Regulatory Costs, an analysis of how much the adoption of new rules could cost affected parties, didn’t accurately estimate losses to the exotic pet trade. He said the agency didn’t take into account businesses that sell pet food, caging, lighting and other services to reptile keepers.

During three hours of public comments, several reptile breeders said current regulations, including the conditional species permitting mechanism, could be used to control iguana and tegu breeding. They said that prohibiting these species may create a black market for sought-after lizards and snakes.

Some breeders said most of their clients are not in Florida, and that they breed specialty morph lizards with unique colors that are in high demand and aren’t as likely to survive in the wild because of genetic mutations.

Pete Brandre, owner of Incredible Pets in Melbourne, said the majority of tegus and iguanas produced in Florida are morphs which are more sensitive to the sun due to their lack of pigmentation. They also have vision problems, which reduces their chances of surviving and reproducing in the wild, he said.

“And their value is so high that nobody will release them,” Bandre said, adding that these morphs are worth thousands of dollars.

Pet owners and enthusiasts called into the meeting to comment on their love for their reptile pets. A caller called Jasmine said her pet lizards helped her deal with bipolar disorder.

“They are more than just pets to me, they are like my sons and daughters,” she said.

But pets just like those have escaped or been released repeatedly in the state, leading to widespread problems and declines in native species. The ubiquitous green iguana, for instance, has exploded in population and done widespread damage to landscaping, shorting out power to communities and undermined drainage canal banks.

During the meeting, commissioners said several times that pet owners don’t need to get rid of their pets right now as they will be allowed to keep them for the life of their animals by obtaining a no-cost permit. They also amended the rules to give pet owners and breeders 180 days instead of 90 days to comply with new regulations such as stricter specifications for where reptiles are kept.

“The floors of outdoor enclosures shall be of concrete or masonry block construction at least two (2) inches in thickness. Sides shall be constructed of concrete at least eight (8) inches in thickness, with a minimum height of four (4) feet above the floor of the enclosure,” said one of the rules.

FWC said Florida has the most invasive reptile species in the U.S. because of its welcoming subtropical climate and plentiful food availability, multiple ports of entry and vibrant trade in exotic animals. Commercial breeding for sale and pet ownership play a significant role in raising the odds that an invasive species will become established because it increases the number of animals that can potentially escape or be intentionally released, FWC said.

Ecological impacts can include feeding on native species, as is the case with Burmese pythons eating small mammals like marsh rabbits, raccoons and even small deer, as well as competition with native animals for food. Habitat alteration, which iguanas have been documented to cause in Florida, can also affect native species.