The productivity science behind biophilia is about much more than plants

Humans in the modern world spend a lot of time indoors.

Americans reportedly stay inside for up to 93% of their lifetimes when you combine the hours spent indoors and in transport, according the the Environmental Protection Agency.

Yet studies show that people who can experience nature and the elements are mentally and physically healthier than those who don’t.

There’s a reason for this: Biophilia.

The concept of biophilia, which refers to our “love of life or living systems,” states that humans have an inborn need for contact with nature and that this connection is essential to our health and wellbeing.

Exposure to nature has shown a positive impact on reducing recovery time for surgical patients. A study on children diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder showed taking children for walks in nature improved their ability to focus. An emerging treatment method in Japan called “forest medicine” showed improved blood pressure levels in patients after they spent a period of time surrounded by natural forests.

Biophilia can explain why people choose to vacation in the great outdoors, relax on a beach, or camp in a forest. It’s what makes an office worker opt to spend a lunch hour outside and stroll through a park, and what inspires a diner to prefer a restaurant with outdoor seating. It’s also the reason people will spend more money on a hotel room that has a view of nature.

Biophilic designs mimic nature or expose people to actual nature in some way.

In the workplace, biophilic interior design has been seen to reduce absenteeism and mental fatigue, promote emotional satisfaction, and increase productivity.

In other words, getting in touch with nature is good for a company’s bottom line, and may hold some clues about how to promote and maintain a robust economy.

Research says our relationship with nature is essential to our physical and mental health and overall wellbeing, which explains why biophilic design is such an important consideration for our interior environments.

But while most interior design professionals are familiar with the concept of biophilic design, many only recognize a limited few of the countless ways it can be implemented.

An understanding of biophilic design is often limited to adding greenery to a space, for example—which explains the growing popularity of sprawling green living walls, green roofs, and tastefully arranged potted plants in offices and retail spaces.

Living systems

If you Google “biophilic design,” you’ll see something like this:

It’s about much more than plants and greenery.

But plants are only the tip of the biophilic design iceberg, so to speak.

So, what is biophilic design beyond plants, greenery and naturescapes?

Let’s take a look at how biophilic design can be implemented where most working people spend up to a third of their waking hours: the office.

As stated earlier, biophilic design in the office can help lower employee’s stress levels, reduce mental fatigue and burnout, and promote a healthy environment. To illustrate the many ways biophilic design can be implemented, I created a biophilic model tailored to corporate interior designers, especially those who work in cities where access to nature may be limited. (My model is based on other popular ones, including the environmental design firm Terrapin Bright Green’s “14 patterns of biophilic design.”)

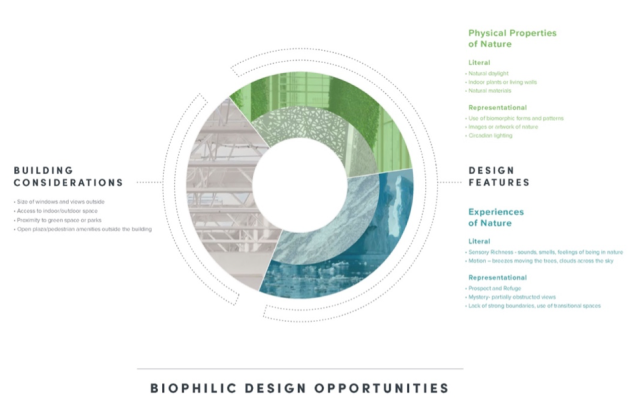

The two main opportunities for implementing biophilic design are “building considerations”—meaning building features that offer opportunities for biophilic design, and “design features”—replicating physical properties and/or experiences of nature in a literal or representational way.

These still only represent a small fraction of the many biophilic design strategies!

Bringing biophilia to work

Biophilic interior design reduces absenteeism and mental fatigue, promotes emotional satisfaction, and increases productivity. Interior designers who work on corporate renovation projects in cities tend to have little control over building considerations; we are not typically able to specify a window’s size, or a building’s orientation, because we’re working with an existing structure. But if a building is located next to a park or body of water, for example, designers can create elements that overlook natural landscapes, or in some way incorporate the natural surroundings. Another building consideration is indoor-outdoor space. While not necessarily easy to design in many major cities, biophilic design features can take the form of incorporating an outdoor terrace or roof patio. The goal is to create designs that encourage a building’s occupants to spend more time outdoors, for example by planting vegetation and gardens alongside seating and common areas to create places where people want to spend their time working or socializing.

You may read this and say to yourself, “Duh, why wouldn’t I feature the best view in a high-profile area such as a café or conference center? Why wouldn’t I design a terrace to be a destination for all employees? That’s just good design!”

And I agree—you are completely correct. But it is important to understand that these are good design decisions precisely because of their biophilic potential.

Does this indoor/outdoor space make you want to get to work?

Unlike with building considerations, interior designers have complete control over design features. Replicating the physical properties of nature has to do with the aesthetic qualities of nature, whereas our experiences of nature do not rely on aesthetics at all.

Biophilic designs that feature literal physical properties of nature include greenery and plants, natural daylight, engineered light that mimics natural daylight, raw natural materials such as wood and stone, water features, and live fire in fireplaces.

Representational physical properties of nature can take the form of displayed images of nature, a natural color palette, biomorphic shapes and patterns, and even circadian lighting. These design features are meant to recreate aesthetic qualities of nature without actually using the real thing.

Nature does not have right angles.

A different type of office cloud shows representational physical properties of nature.

An example of a “representational experience” of nature is when designers create opportunities for prospect and refuge. Natural environments that appeal to humans often offer simultaneous opportunities for prospect (the ability to have a distant view of a thing) and refuge (the ability to feel safe, usually by having one’s back protected).

This ability to “see without being seen” can be replicated in the interior environment through the strategic placement of booth seating or high-back chairs in an open environment, and provide comforting protection while still allowing a person to be engaged and aware of their surroundings.

Bonus biophilic feature: Obstructed views through perforated felt panels provide a representational experience of mystery and intrigue also felt in nature.

There’s been a shift in how corporations, public offices, and educational institutions have been thinking about the spaces we inhabit, spurred in large part most likely by the growing focus on wellness among the interior design industry.

The trend has had a notable impact on corporate design, as more business leaders are recognizing that promoting human health and wellbeing has a positive impact on the bottom line.

Design certifications like the WELL Building Standard and a number of industry best practices have started to promote physical activity, social interaction, new types of work environments, healthy foods, and new standards for our indoor environments, all as part of corporate interior design.

By promoting human health and wellbeing through design, biophilic design is another emerging strategy that indicates where the future of the design industry is headed. Connecting with nature shouldn’t be seen as an option when science proves how vital it is to our health and happiness.

While these formal practices of biophilic design are still new, people have started to realize that investing in human health is both good business, and good design.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: