Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America and the Importance of Dialogue Across Divides

The lighter clicks as his mother fans it beneath a heroin-filled spoon. His 5-year-old belly growls. A foster mother’s fist thunks against the sink as she thrusts his hand into the garbage disposal’s spinning teeth. An officer’s fist crunches into his nose at a residential community for at-risk boys. Clank go the handcuffs around 11-year-old wrists—the work of a truancy officer who correctly identified him as a runaway, but never asked why.

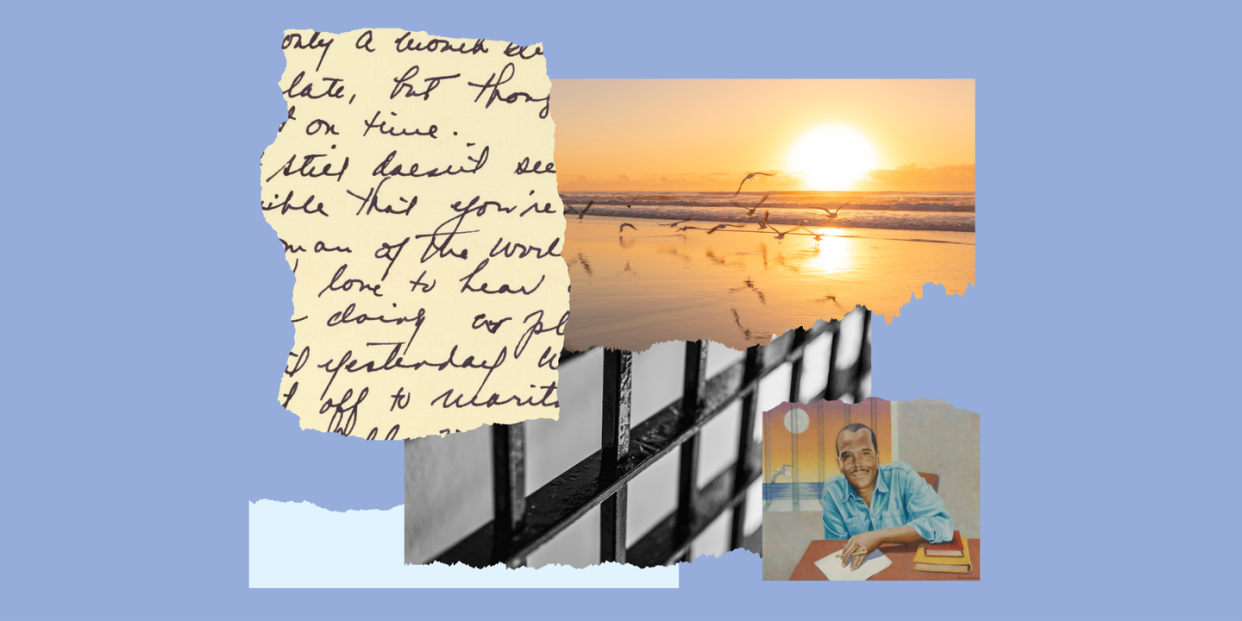

This is the soundtrack to a splintered life.

In That Bird Has My Wings, Jarvis Jay Masters’s debut memoir, readers are thrust into painful scenes familiar to too many Black American boys born into addiction and poverty. His story reads as a blueprint for the incarceration pipeline: The small child siphoned off from the most basic forms of care becomes the young man who seeks safety and shelter through the promise of crime—and is punished accordingly. This is where the story, as it has for many, could have easily ended.

Instead, Masters transforms himself again.

How does one shift from being a convicted felon serving a sentence on death row, an identity framed by familial neglect and state abuse, to a Buddhist thinker mentored by revered spiritual teacher Pema Chödrön, to a celebrated writer endorsed by Oprah? Clues to Masters’s extraordinary trajectory can be found in a poem that won PEN America’s Prison Writing Awards in 2005.

Masters’s poem “Recipe for Prison Pruno” braids together, line by line, two disparate sets of instructions: a recipe for brewing moonshine alcohol in prison interwoven with his own death sentence, rendered in the presiding judge’s voice. The form itself is a literary revelation, marking the cruel inventiveness Masters was forced to develop first as a foster child, then ward of the state, and, later, an inmate at many carceral institutions. The poem mimics the way trauma sneakily intertwines itself with desperate methods of warped control and relief, and how living under systemic duress buries one’s soft-hearted center under the sharp edges of survival.

I have hereon set my hand as Judge of this Superior Court,

with a spoon, skim off the mash,

and I have caused the seal of this Court to be affixed thereto.

pour the remaining portion into two 18 oz. cups.

May God have mercy on your soul.

Though the poem offers no respite or resolution of its own, it is through the act of braiding that Masters creates a symbolic reclamation. Masters has pulled apart, then pieced together, the narrative threads impressed upon him. He has taken the words into his own hands. He has begun to reassemble the splintered self.

And then, he offers the result to the world. —Caits Meissner and Nicole Shawan Junior

NICOLE SHAWAN JUNIOR, Deputy Director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America:

That a death sentence can be uttered in a single breath, in one sentence, and take up only half a poem—a sole thread in a literary braid—but carry an unbearable weight crushes me. As I reread each line, I imagine the juxtaposed scenes: Masters in the courtroom, devastated at hearing the court’s sentence, thrown against Masters’s quiet focus in a California prison cell, step by step brewing a liquid antidote. I wonder if my cousin Duval, incarcerated for over a decade after pleading to life in prison to escape South Carolina’s death penalty, knows the same recipe. Has he made it?

How do Black boys, children, born into addiction, poverty, and systemic oppression like Masters and Duval make it? How can we handle the unfathomable load?

In Nichiren Buddhism, Daisaku Ikeda instructs that “the Lotus Sutra teaches of the great hidden treasure of the heart, as vast as the universe itself, which dispels any feelings of powerlessness. It teaches a dynamic way of living in which we breathe the immense life of the universe itself. It teaches the great adventure of self-reformation.”

Through his Buddhist journey, and the writing that followed, Masters has crafted meaningful art out of a life of pain that offers us all, touched by incarceration or not, valuable insight into how we can shape our own narrative, and even create our own joy. He shows that hidden within each and every human being is a limitless treasure of good and power, and when tapped, we can find peace with our parts, and reclaim our whole.

It’s this mystic truth and a journey not dissimilar to Masters’s that led me to my role as deputy director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America.

Though I have never suffered the despair of death row or life in prison, like Masters, I learned early to disassociate from my environmental conditions by splintering myself. Back then, Daddy was always on a mission for crack and Mama was always at a job, working to make the ends that Daddy stole meet. Every night at home alone, I pulled covers up to my neck, pushed my head under a pillow, and hid from the crackheads I expected would break into our home, rob me, or worse. When my fear got the best of me, I’d tiptoe into the living room to check the window furthermost to the right, its iron burglar bars the only boundary between our apartment and the fire escape. Some nights I spent hours checking that no one lurked beyond that metal barrier.

These childhood memories, formed by addiction, poverty, and neglect, propelled me onto my own path: a former career prosecutor, a current felon convicted of fraud and sentenced to probation’s iron grip, a published writer and Nichiren Buddhism neophyte. At PEN America, I do the work of celebrating and amplifying justice-involved writers like Masters because I know the power made available by the written word and spirituality. It’s the same power that stitched me back together, that saved me whole.

Nicole Shawan Junior (they/them) is deputy director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America. They founded Roots. Wounds. Words.—an organization that provides BIPOC-led and -centered literary arts pedagogy, publication, and performance opportunities. Junior’s writing appears in The Sentences That Create Us, Guernica, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. They served as editor-in-chief of Black Femme Collective.

CAITS MEISSNER, Director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America:

Long before I became director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America, I had been sneaking Masters’s “Recipe For Prison Pruno” into prisons and jails. Though I knew that the ingredients to make prison hooch were no secret—and easy enough to find out in the unit, on the yard—I also understood the poem’s description would be considered contraband by the powers that be. My small risk was worth the lesson in literary craft for my students, but moreover, it was a powerful example of how one can repurpose what harms ourselves and others into potent medicine. It also reminded me that imagination, knowledge, and clarity of mind are mighty threats to systems of oppression. Perhaps there is nowhere in America where a poem, a page, a memoir is more dangerous than in prison.

PEN America, a 100-year-old nonprofit that celebrates and defends free expression, started the Prison and Justice Writing program on the heels of the Attica uprising. It was shaped by the conviction that writing is a legitimate form of power. For more than 50 years, our programs have evolved, offering free resources, mentorship, and public platforms to incarcerated writers across the country. We collaborate with many who share Masters’s soul-determination. Like Masters, many writers in prison are recording their stories by any means necessary, with an outdated typewriter, a pencil, or the flimsy ink filler of a pen (the only utensil permitted to Masters on death row). Incarcerated writers face a myriad of barriers to expression—lack of internet access, prohibitively expensive phone systems, the reliance on physical mail in a digital world, censorship, and punitive retaliation, to name a few.

And yet, there are plenty of incarcerated writers willing to take the bold risks necessary to have their voices heard and communed with, to teach about the resilience of the human spirit, about the conditions and consequences of a punitive system that has spiraled out of control. PEN America’s recently published book The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison, reaching 75,000 people in prison for free with funding from the Mellon Foundation, is a compilation of contributors from the invisibilized community of justice-involved writers, truth tellers, and creatives that Masters shares.

As PEN America marks its centennial, it is encouraging to see a significant increase in the number of published works written by non-celebrity incarcerated writers entering the mainstream. As a result of this trend, writers behind the walls have been able to directly communicate with those of us on this side. We, in turn, are able to sit with, discern, and understand the complexity of guilt and innocence, past and present, the fragmented parts versus the whole. It is at this meeting point where dialogue is opened across divides, stigmas are disrupted, and new possibilities are imagined. This important conversation is only available because incarcerated writers like Jarvis Jay Masters, despite the perils of their condition, scratch out the narratives of their lives, welcome us to commune with their most vulnerable parts, and, in so doing, help us access the treasure we all hold within.

Caits Meissner is director of Prison and Justice Writing at PEN America, where she edited The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison (Haymarket Books). Meissner’s poems, comics, essays, and curation have appeared in The Creative Independent, The Rumpus, and Harper’s Bazaar among others.

You Might Also Like