The preposterous story of Adam Vinatieri

Only a few weeks after the NFL hired him to find punters and placekickers worthy of a tryout with the World League of American Football, Doug Blevins realized he underestimated the interest he would receive.

A deluge of out-of-work kickers bombarded Blevins with so many highlight tapes that the hill of unwatched VHS cassettes cluttering his desk seemed to grow larger by the day.

Somewhere in that heaping pile was a tape sent by a self-taught 22-year-old kicker from South Dakota with big ambitions but a modest track record. In 1995, very little about Adam Vinatieri’s résumé suggested he had an NFL future, let alone that he’d one day be known as the league’s king of clutch kicks.

In four erratic seasons at Division II South Dakota State, Vinatieri showed off a powerful leg but missed as many field goals as he made. His inconsistency even got him benched for two games midway through his junior season in favor of a toe-kicking defensive lineman.

Vinatieri’s tape might have stayed buried on Blevins’ desk for months had the young kicker not called day after day to pester the kicking guru about watching it. One Saturday morning, Blevins finally relented and popped the tape in his machine. Much to his surprise, the clips of Vinatieri booming footballs through South Dakota’s howling winds and heavy snowfall left him more intrigued than he expected to be.

“The ball exploded off his foot,” Blevins recalled. “He’d hit the ball a mile, but he had no idea where it was going to go. He had the leg speed and the leg strength, but what he was missing was the mechanics. It was like he had a cannon attached to him, but he didn’t know how to load it or aim it.”

Hearing that Blevins saw potential in him and wanted to work with him was all the reassurance Vinatieri needed to continue his unlikely pursuit of an NFL gig. Blevins asked how long Vinatieri would need before he could get to Virginia.

“Give me two days,” Vinatieri replied.

When Vinatieri boarded his flight to Virginia, he knew Blevins only as a kicking coach who had consulted for the New York Jets the previous season. He had no idea there was anything unusual about Blevins until a short, stocky man rolled up to him at the airport arrivals lounge with his right hand outstretched.

Blevins told Vinatieri that he had been confined to a wheelchair his whole life because of cerebral palsy, that the condition had taken his legs but never affected his mind. That was how Vinatieri learned the fate of his floundering kicking career rested on a man who had never actually kicked a football before.

* * * * *

There’s no Adam Vinatieri without Doug Blevins, no Super Bowl-clinching kicks, no age-defying longevity and no record-setting, field-goal streak. In fact, were it not for Blevins’ guidance and influence, Vinatieri, 45, might be working as a heart surgeon right now instead of poised to break another of the NFL’s most significant records.

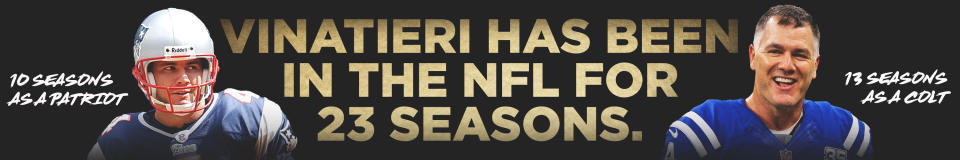

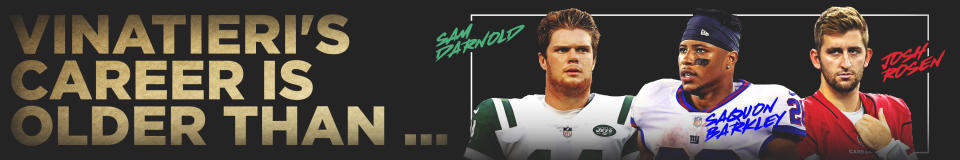

In Sunday’s game in Oakland, Vinatieri made two field goals and an extra point, which pushed him past retired kicker Morten Andersen as the NFL’s all-time leading scorer. That’s an unfathomable feat for anyone, let alone a kicker whose football career began so humbly.

Vinatieri didn’t attend punting or kicking camps growing up, nor did he receive private instruction from any kicking gurus. He began kicking only on a whim in fifth grade when his Pop Warner coach asked if anyone on the team felt comfortable giving it a try.

“There were three kids who volunteered, and Adam was one of them,” said his father, Paul Vinatieri. “They all took a shot at kicking, and Adam was the best. That’s how he got started.”

Vinatieri handled kicking and punting duties for Rapid City Central High School, but by no means was he a traditional specialist. He was also an option-style quarterback and a linebacker who delighted in driving opposing ball carriers into the turf. When he dreamed about playing professional football, he always envisioned himself as the next John Elway or Mike Singletary, not the next Jan Stenerud or Ray Guy.

Too small to play quarterback or linebacker beyond high school, Vinatieri accepted a partial scholarship to punt and kick at South Dakota State. He endeared himself to South Dakota State coach Mike Daly by serving as the team’s third-string quarterback and by enduring all the same conditioning drills and weightlifting routines the rest of his teammates did.

While Vinatieri hit a couple of 51-yard field goals at South Dakota State and set a school record by averaging 43.5 yards per punt as a senior, his accuracy was not nearly as impressive as his leg strength. He missed so many field goals and extra points early in his junior season that Daly actually held a team-wide audition to find a new kicker to replace Vinatieri.

“We ended up going with a defensive lineman named Jim Remme, a square-toed, straight-on kicker,” Daly said. “He took over for two games, but then he missed his first few field goals and we put Vinnie back in.”

Vinatieri regained his groove the latter half of his junior season, but then he hit only four of 13 field goals as a senior. The gusty, snowy South Dakota weather contributed to Vinatieri’s woes, as did the challenge of handling both punting and kicking and never having a kicking coach to help him improve his technique.

“We couldn’t help him with the little things, so he had to learn through trial and error,” Daly said. “As we were going through drills with the offense and defense, he’d go over to the other field and just kick by himself. He understood we couldn’t coach him very much. I’d go over to watch him and he’d very respectfully tell me, ‘Now don’t really tell me much.’ ”

Even though no NFL coaches or scouts he contacted about Vinatieri showed a shred of interest, Daly still had an inkling his kicker possessed the talent and perseverance to play professional football. As a result, Daly plucked Vinatieri’s No. 7 jersey out of the dirty laundry hamper after his final college game so he’d have a keepsake in case his long-shot premonition came true.

* * * * *

For awhile it looked like Daly should have left his memento in the laundry bin. Vinatieri returned to his parents’ house after graduation and worked odd jobs while trying to figure out if he could keep pursuing kicking or if it was time to apply to medical school.

The turning point was Blevins’ invitation to come train with him in Virginia. Instead of relying on trial and error to achieve the consistency he lacked, Vinatieri suddenly could tap into the mind of a man who had studied the art of kicking for decades.

Relentless in his desire to make a living working in football despite his handicap, Blevins kept statistics for a local Pop Warner team as a kid and served as a student assistant for his high school team. When he noticed his high school’s kickers weren’t very proficient, he wrote a letter to Dallas Cowboys kicking coach Ben Agajanian seeking advice on how he could help them improve.

That experience taught Blevins that coaching kickers might be his most realistic path toward a career in football. Few coaches knew much about the mechanics of kicking a football, so Blevins believed he could make himself valuable if he made that his specialty.

In high school, Blevins studied video of NFL kickers, combed through every instruction manual he could find and began a regular correspondence with Agajanian. He noted similarities in the techniques of the most successful kickers, from the number of steps they took in their approach, to the way they squared their bodies, to where they put their plant foot.

Blevins put his theories into practice, first as a student assistant and later as a private kicking coach and NFL consultant. He has worked with dozens of college and NFL kickers and punters over the course of his career, but he has yet to find anyone more eager to learn than Vinatieri.

A couple weeks into their time working together, Blevins got up before dawn and discovered Vinatieri’s pickup truck parked in his driveway. Vinatieri was sleeping in the bed of the truck, and all of his belongings were still packed up inside.

“He had told me that he had a place to live, but he really didn’t,” Blevins said. “I realized then that he would do whatever he needed to do to get to the NFL, and that included sleeping in his vehicle.”

After Blevins helped Vinatieri find a tiny apartment and a bartending job, their focus returned to the practice field. They kicked four or five days a week for months, ending each practice session with a 47-yard field goal attempt to win the Super Bowl.

By the following spring, Vinatieri was a different kicker. At last, he could properly load and aim his cannon of a leg. His hip-shoulder alignment was perfect, his leg swing was free and easy and he positioned his plant foot exactly the same way every time.

When Blevins sent Vinatieri to Atlanta to try out for the World League’s Amsterdam Admirals, special teams coach Al Tanara came away stunned that an NFL team hadn’t snapped him up already.

“It sounded like a shotgun went off when he kicked the ball,” Tanara said. “It wasn’t much of a question who our kicker was going to be. The other guys were good, but they weren’t as long or as accurate as he was.”

Vinatieri hit nine of 10 field goals for Amsterdam in 1996 and also served as the team’s primary punter that season. He returned home in June to a dream come true: An invitation to training camp from an NFL team.

* * * * *

The New England Patriots didn’t enter the 1996 offseason desperate to find a kicker. They still had Matt Bahr, who was 40 years old but also coming off a solid season in which he hit 16 of 23 field goals, including a career-best 55-yarder.

Bahr might have held onto his job for another year had New England special teams coach Mike Sweatman not watched Vinatieri kick at a camp Blevins held just before World League players left for Europe. Sweatman left that camp impressed enough with Vinatieri that he requested the young kicker’s game tape throughout the 1996 World League season.

“He had a good technique and he drove straight through the ball,” Sweatman said. “And if you spent any time around him, you knew he was a great kid.”

At Sweatman’s recommendation, Bill Parcells invited Vinatieri to training camp to serve as competition for Bahr, but the New England coach had no intention of jettisoning his trusted veteran and entrusting kicking to a rookie. The Patriots only envisioned Vinatieri competing to take over kickoff duties from Bahr, who no longer had the leg strength to consistently reach the end zone.

New England’s plans for Vinatieri accelerated in a hurry when he excelled in practice and hit four of six field goals in exhibition play. Rather than burn two roster spots on kickers or risk losing Vinatieri to another team, Parcells called Bahr into his office late in training camp and told the 18-year veteran he was being released.

“I thought we kicked similarly in training camp, but he was the younger guy,” Bahr said. “Knowing Parcells, he was probably looking not only for the current year but also future years. He probably saw that my best years were behind me and his were in front of him.”

The day Vinatieri learned he had survived New England’s final roster cut, one of his first calls was to Blevins.

“There was a kicker in New England released today,” Vinatieri shouted into the phone, “and by God it wasn’t me!”

A few days later, Vinatieri showed up at Blevins’ apartment with a copy of his new contract and a list of people who had told him he wasn’t good enough to make the NFL.

“He faxed copies of his contract to every person on his list,” Blevins said with a chuckle. “I tell you, I laughed so hard I about cried. It was hilarious.”

Vinatieri’s hubris almost came back to bite him two games into his rookie season when he missed three of the four field goals he attempted in Buffalo. Parcells made it clear to Vinatieri that another performance like that would not be tolerated, but the young kicker redeemed himself in the ensuing weeks before winning over his coach for good by running down Dallas running back Herschel Walker from behind on a long kickoff return.

While all the milestone moments in Vinatieri’s career have been special for Blevins to watch, none will top the final play of Super Bowl XXXVI. Vinatieri sealed New England’s upset victory over the St. Louis Rams by drilling a game-winning 48-yard field goal, just 1 yard longer than the ones they used to practice back in Virginia.

As that kick split the uprights, Blevins was watching from a sports bar in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he was scheduled to give a speech the following day. The short, stocky man in the wheelchair wept uncontrollably as his former pupil jumped up and down, raised his arms in victory and hugged every teammate in sight.

“Here I am watching the Super Bowl, crying, snot flying out of my nose,” Blevins said. “That bartender and those waitresses had to think I was nuts.”

Blevins’ ex-wife tried to explain that he was Vinatieri’s coach, but nobody at the bar appeared to take her seriously.

The story of a disabled coach transforming an unwanted kicker into a Super Bowl hero was just too preposterous to be true.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Jeff Eisenberg is a writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email him at jeisenb@oath.com or follow him on Twitter!

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Red Sox snub former star for pregame Series ceremony

• Tim Brown: Dodgers headed for disappointment again?

• Jeff Passan: The 15 minutes that may have swung the World Series