Plan to house migrants at former Chicago school delayed amid community pushback; mayor says city is at ‘maximum capacity’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

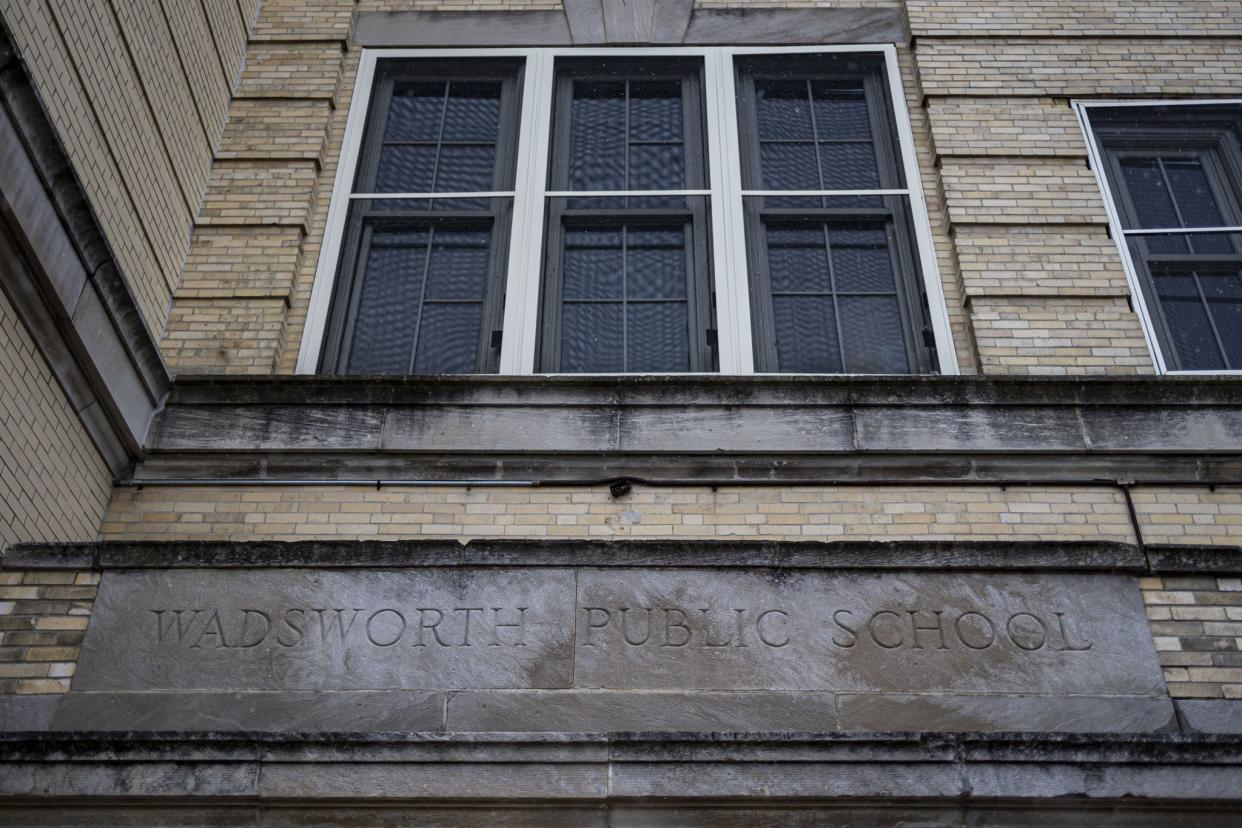

Outside a former South Side elementary school that was chosen to shelter migrants arriving in Chicago, a small group of protesters gathered Thursday morning clamoring for their needs to be taken care of first.

The plan for the building now appears to be in limbo and its opening delayed, according to the local alderman.

The Woodlawn residents said they opposed the transformation of the neighborhood’s shuttered Wadsworth Elementary School into temporary housing for migrants who have been bused to Chicago. The opponents argued their already-struggling community cannot take on another influx of those in need.

“While I’ll love to help immigrants and everybody else, I’ll like to help my own first,” said longtime Woodlawn resident Jean Clark.

The uproar comes after the city confirmed last week that the old school would be refurbished as a temporary shelter to help address the recent surge of migrants, about 4,000 of whom have arrived to Chicago since August — mostly on buses from Texas as part of Republican Gov. Greg Abbott’s controversial strategy to send migrants to “sanctuary cities” controlled by Democratic leaders, rather than expend his state’s resources. About 1,500 remain in the city’s care, Chicago officials said, though buses from border states are no longer arriving on a regular basis.

The city has decided to press pause on the Woodlawn shelter, Ald. Jeanette Taylor, 20th, told the Tribune Thursday evening. A meeting will be held next week with the mayor’s office, Taylor, constituents and Chicago police to determine the fate of the building.

Taylor said the opposition from the neighborhood should not be seen as anti-immigrant sentiment but rather as local residents feeling disrespected by the city’s plan to repurpose a school that the community had fought to keep open. While some residents oppose the shelter completely, others just want to make sure that there is safety in place to ensure the well-being of the migrants in a community they don’t know.

“This is not just about the migrants; this is about our Black and brown solidarity,” Taylor said, adding she works with the Spanish-speaking community and Latino constituents. “So this rhetoric of us against them is, no, this is a sanctuary for all. This should be us taking care of each other.”

The protesters said they worried the incoming migrants would drain the few resources available for their community, demanding the mayor instead divert funding from the shelter to create housing for the local homeless population or to other tools for stemming violence and poverty.

“The resources that they’re pouring into the building for the migrants, we don’t have those,” said Jennifer Maddox, a community leader who organized the rally. “So it’s unfair to say we’re going to provide all these resources for the immigrants but we disregard the people that are already here.”

Officials from Chicago and Illinois have struggled to secure housing and other resources for these migrants, with Mayor Lori Lightfoot recently asking the state for $54 million in additional emergency funding.

The city did not respond to inquiries on the status of the plans to house migrants at the former Wadsworth building, at 6420 S. University Ave. In a tweet Thursday, Lightfoot praised the announcement by President Joe Biden’s administration that it will expand immigration enforcement at the southern border, while she said Chicago was “at maximum capacity.”

“As a welcoming city, Chicago has a responsibility to treat asylum seekers with dignity and respect, which we have and will continue to do,” Lightfoot said. “However, like other cities across the country, we are at maximum capacity in housing and services. Thus, it would simply be inhumane for cities and states to continue sending migrants to Chicago.”

Maddox, who is running against Taylor for 20th Ward alderman, said she’s yet to hear a security plan for the Woodlawn shelter or a timeline of how long it would remain open or whether there could be background checks of migrants who would be housed there.

One by one, the residents behind her echoed her concerns.

“We are very disappointed in this decision that Mayor Lightfoot has made to place these migrants in our community without our permission,” said one protester who declined to give their full name. “Please withdraw your decision to put the migrants in our community; there’s plenty of room in Little Village for their people.”

Ald. Raymond Lopez, 15th, a frequent Lightfoot critic, said he was troubled by such comments because to him, it showed how Black residents were being pitted against asylum-seekers. He said there was no need to fight over scraps when the city still has an arsenal of federal COVID-19 stimulus dollars to help both communities.

“We are unnecessarily causing tension and friction between African Americans and Latinos,” Lopez said. “It was painful to watch … to see the amount of pain caused to Woodlawn and the amount of ignorance that it’s creating. … Democratic cities are absolutely helping prove the point that many of the big cities that say they are welcoming are welcoming in name only, as long as no one shows up.”

Ulysses Blakeley, one of the Woodlawn protesters, said the migrants should be placed in areas where they can easily access resources to establish their new lives.

“It is not that we don’t want to assist the immigrants,” Blakeley said. “I have immigrants in my family. I understand what the issues are. But you cannot unilaterally put down a large, very moderate immigrant group in a community without making some comprehensive plan to care for them.”

Baltazar Enriquez of the Little Village Community Council agreed with the concerns of the Woodlawn demonstrators, though he said some of their remarks against the shelter were not welcome.

“(The city is) once again isolating (asylum-seekers) in places where they can find little to no help,” Enriquez said in a phone interview.

The latest tension over the city’s new migrants comes as state officials have outlined the second phase in their migrant resettlement plan.

A letter sent to legislators from Illinois Department of Human Services Secretary Grace Hou said no sooner than Jan. 15, new arrivals and current asylum-seekers in hotels will be moved to temporary congregate housing facilities, which will have partitioned sleeping areas with up to 10 cots and individual lockers. They will get three meals a day, have access to restrooms and can stay up to 90 days. Family areas will be separate from those for single men and women.

A spokesperson for Hou said up to three congregate housing shelters will be set up in Cook County. The Woodlawn proposal is not one of them but rather a pending shelter operated by the city.

“IDHS aims to empower asylum seekers to make informed decisions about their futures for themselves, and the goal of (the new housing approach) is to support individuals in their journey to independence as quickly as possible,” Hou spokesman Patrick Laughlin wrote in a statement.

Chicago City Council Latino Caucus Chair Ald. Gilbert Villegas, 36th, did not take issue with the latest plan but knocked the mayor for what he said was a lack of communication with local aldermen and, by proxy, their residents — especially in a community like Woodlawn that is still hurting from decades of disinvestment.

“These are situations that are being pushed on us by border states,” Villegas said about the congregate living facility at Wadsworth. “It is a little tight and uncomfortable, but we’re trying to make it as humane as possible. … I just wished the (Lightfoot) administration would have communicated more.”

Villegas also called on the federal government to “act a little bit quicker” as cities like Chicago continue scrambling for resources. He said he has invited officials from the U.S. Department of Housing and Human Services to tour the city’s facilities in the coming weeks.

“There’s really no way to prepare for this,” Villegas said. “This is more of an example of flying a plane while you’re building it.”

Carlas Prince Gilbert, another resident of Woodlawn, said that she understands the importance of shelter and housing, but asked, “What is the plan to integrate them to the community?”

Tribune’s Gregory Pratt contributed.