A pipe dream, or a possibility? Water experts debate 1,500-mile aqueduct from Cajun Country to Lake Powell.

Two hundred miles north of New Orleans, in the heart of swampy Cajun Country, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1963 cut a rogue arm of the Mississippi River in half with giant levees to keep the main river intact and flowing to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Old River Control Structure, as it was dubbed, is also the linchpin of massive but delicate locks and pulsed flows that feed the largest bottomland hardwood forests and wetlands in the United States, outstripping Florida’s better known Okefenokee Swamp.

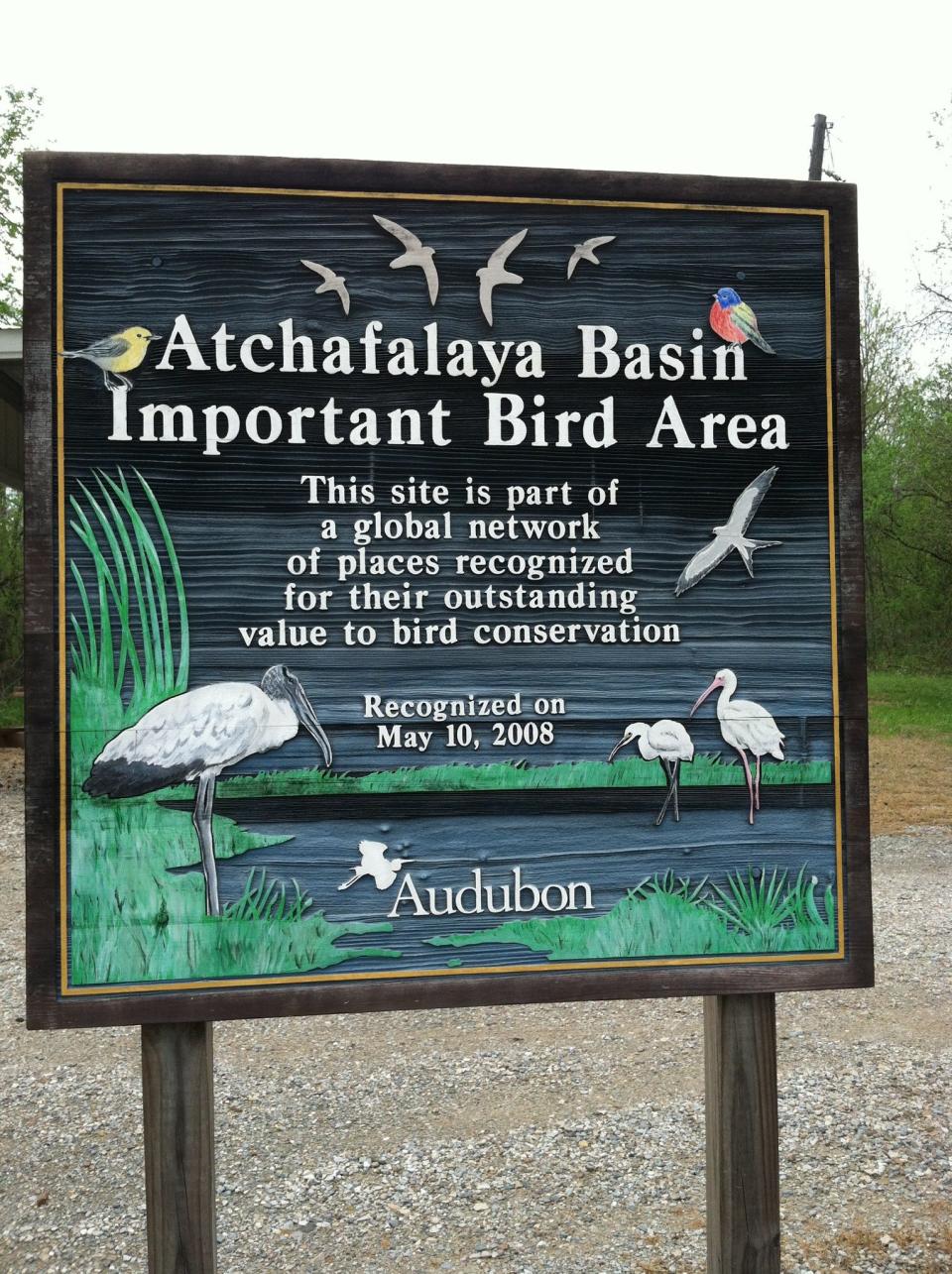

Clouds of birds – hundreds of species – live in or travel through Louisiana’s rich Atchafalaya forests each year, said National Audubon Society Delta Conservation Director Erik Johnson. They include gawky pink roseate spoonbills, tiny bright yellow warblers, known as swamp candles because of their bright glow in the humid, green woods, and more.

This summer, as seven states and Mexico push to meet a Tuesday deadline to agree on plans to shore up the Colorado River and its shriveling reservoirs, retired engineer Don Siefkes of San Leandro, California, wrote a letter to The Desert Sun of the USA TODAY Network with what he said was a solution to the West's water woes: Build an aqueduct from the Old River Control Structure to Lake Powell, 1,489 miles west, to refill the Colorado River system with Mississippi River water.

A BODY IN A BARREL, GHOST TOWNS, A CRASHED B-29: What other secrets are buried in Lake Mead?

“Citizens of Louisiana and Mississippi south of the Old River Control Structure don’t need all that water. All it does is cause flooding and massive tax expenditures to repair and strengthen dikes,” wrote Siefkes. "New Orleans has a problem with that much water anyway, so let’s divert 250,000 gallons/second to Lake Powell, which currently has a shortage of 5.5 trillion gallons. This would take 254 days to fill.”

The letter and others with an array of ideas generated huge interest from readers around the country – and debate about whether the concepts are technically feasible, politically possible or environmentally wise. Seeking answers, The Desert Sun consulted water experts, conservation groups and government officials.

Engineers said the pipeline idea is technically feasible. But water experts said it would likely take at least 30 years to clear legal hurdles. And biologists and environmental attorneys said New Orleans and the Louisiana coast, along with the interior swamplands, need every drop of muddy Mississippi water.

The massive river, with tributaries from Montana to Ohio, is a national artery for shipping goods out to sea. And contrary to Siefkes' claims, experts said, the silty river flows provide sediment critical to shore up the rapidly disappearing Louisiana coast and barrier islands chewed to bits by hurricanes and sea rise. Scientists estimate a football field's worth of Louisiana coast is lost every 60 to 90 minutes. Major projects to restore the coast and save brown pelicans and other endangered species are now underway, and Mississippi sediment delivery is at the heart of them.

Siphon off a big portion, and “you’d be swapping one ecological catastrophe for another,” said Audubon’s Johnson.

'My water, your water. My state, your state'

Nonetheless, Siefkes’ trans-basin pipeline proposal went viral, receiving nearly half a million views. It’s one of dozens of letters the newspaper has received proposing or vehemently opposing schemes to fix the crashing Colorado River system, which provides water to nearly 40 million people and farms in seven western states.

Fueled by Google and other search engines, more than 3.2 million people have read the letters, an unprecedented number for the regional publication's opinion content.

Many saw Siefkes' idea and others like it as sheer theft by a region that needs to fix its own woes.

CLIMATE POINT: Subscribe to USA TODAY’s free weekly newsletter on climate change, the environment and the weather

“Let's be really clear here. As a resident of Wisconsin, a state that borders the (Mississippi) river, let me say: This is never gonna happen,” wrote Margaret Melville. “What states in the Southwest have failed to do is curtail growth and agriculture that is, of course, water-driven."

But desert defenders pushed back. John Neely of Palm Desert, California, responded: "All of these river cities who refuse to give us their water can stop snowbirding to the desert to use our water. The snowbirds commonly stay here for at least six months. Do they thank us for using our water? No. Do they pay extra for using our water? No. They’re all such hypocrites. My water, your water. My state, your state. Last time I heard, we are still the United States of America."

Haul icebergs south? Manufacture rain?

Yahoo, Reddit and ceaseless headlines about a 22-year megadrought and killer flash floods, not to mention dead bodies showing up on Lake Mead’s newly exposed shoreline, have galvanized reader interest this summer.

But grand ideas for guaranteeing water for the arid West have been floated for decades. Haul icebergs from the Arctic to a new southern California port. Run a giant hose from the Columbia River along the bottom of the Pacific Ocean to refill Diamond Valley Reservoir. Grab hydrogen and oxygen from the air and make artificial rain.

'WE'RE GETTING FURTHER AND FURTHER BEHIND': Climate change exposes growing gap between weather we've planned for – and what's coming

As zany as the ideas may sound, could any work, and if so, what would be the costs?

Experts say there’s a proverbial snowball’s chance in August of most of these schemes being implemented. Physically, some could be achieved. This is the country that built the Hoover Dam, and where Los Angeles suburbs were created by taking water from Owens Lake. From winter lettuce in grocery stores to the golf courses of the Sun Belt, the West’s explosive growth over the past century rests on aqueducts, canals and drainage systems.

The bigger obstacles are fiscal, legal, environmental and most of all, political.

"The engineering is feasible. Absolutely. You could build a pipeline from the Mississippi or Missouri Rivers. Would it be expensive? Yes. Do we have the political will? Absolutely not," said Meena Westford, executive director of Colorado River resource policy for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. "I think that, societally, we want to be more flexible. We want to have more sustainable infrastructure. So moving water that far away to supplement the Colorado River, I don't think is viable."

She added, "But it's doable. You could do it."

In fact, she and others noted, many such ideas have been studied since the 1940s. Most recently, in 2012, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation produced a report laying out a potentially grim future for the Colorado River, and had experts evaluate 14 big ideas commonly touted as potential solutions.

The concepts fell into a few large categories: Pipe Mississippi or Missouri River water to the eastern side of the Rockies or to Lake Powell on the Arizona-Utah border, bring icebergs in bags, on container ships or via trucks to Southern California, pump water from the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest to California via a subterranean pipeline on the floor of the Pacific Ocean, or replenish the headwaters of the Green River, the main stem of the Colorado River, with water from tributaries.

A DISASTROUS 'MEGAFLOOD' IN SUNNY AND DRY CALIFORNIA? It's happened before.

While they didn’t outright reject the concepts, the experts laid out multi-billion-dollar price tags, including ever-higher fuel and power costs to pump water up mountains or over other geographic obstacles. They also concluded environmental and permitting reviews would take decades.

"To my mind, the overriding fatal flaw for large import schemes is the time required to become operational. A multi-state pipeline could easily require decades before it delivers a drop of water," said Michael Cohen, senior researcher with the Pacific Institute. He said the most pragmatic approach would only pump Midwest water to the metro Denver area, to substitute for imports to the Front Range on the east side of the Rockies, avoiding "staggering" costs to pump water over the Continental Divide.

But Denver officials have expressed skepticism, because Missouri or Mississippi water is of inferior quality to pure mountain water.

US can't 'engineer our way out' of drought

Not mentioned was the great granddaddy of all schemes for reallocating water, known as the North American Water and Power Authority Plan.

Developed in 1964 by engineer Ralph Parsons and his California-based Parsons Corporation, the plan would provide 75 million acre-feet of water to arid areas in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. An acre-foot is enough water to serve about two households for a year, so it could supply water to 150 million customers.

The total projected cost of the plan in 1975 was $100 billion – or nearly $570 billion in today's dollars, comparable to the Interstate Highway System. The project would require more than 300 new dams, canals, pipelines, tunnels and pumping stations. Its largest dam would be 1,700 feet tall, more than twice the height of Hoover Dam.

Parsons said the plan would replenish the upper Missouri and Mississippi rivers during dry spells, increase hydropower along the Columbia River and stabilize the Great Lakes. He proposed using nuclear explosions to excavate the system's trenches and underground water storage reservoirs.

TAPS HAVE RUN DRY IN A MAJOR MEXICO CITY FOR MONTHS: A similar water crisis looms in the U.S. too, experts say.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, prodded by members of Congress from Western states, studied the massive proposal. Ultimately the rising environmental movement squelched it – the project would destroy vast wildlife habitats in Canada and the American West, submerge wild rivers in Idaho and Montana, and require the relocation of hundreds of thousands of people.

Environmental writer Marc Reisner said the plan was one of "brutal magnificence" and "unprecedented destructiveness." Historian Ted Steinberg said it summed up "the sheer arrogance and imperial ambitions of the modern hydraulic West."

In China, the massive South-to-North Water Diversion Project is the largest such project ever undertaken. Inspired by Mao Zedong, who in 1952 observed, "The south has plenty of water and the north lacks it, so if possible why not borrow some?" and planned for completion in 2050, it will divert 44.8 billion cubic meters of water annually to major cities and agricultural and industrial centers in the parched north.

When finished, the $62 billion project will link China’s four main rivers and requires construction of three lengthy diversion routes, one using as its base the 1,100-mile long Hangzhou-to-Beijing canal, which dates from the 7th century AD.

Meanwhile, watershed states in the U.S., and even counties have taken action to prevent such schemes.

The Great Lakes Compact, signed by President George W. Bush in 2008, bans large water exports outside of the area without the approval of all eight states bordering them and input from Ontario and Quebec.

Other legal constraints include the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Protection Act and various state environmental laws, said Brent Newman, senior policy director for the National Audubon Society's Delta state programs. A Mississippi pipeline to Lake Powell would need to cut across four states, he and Johnson said, including hundreds of miles of wetlands in Louisiana and west Texas.

THE U.S. IS MAKING A BIG DOWN PAYMENT ON CLIMATE CHANGE: Here's what needs to come next.

Large amounts of fossil fuel energy needed to pump water over the Rockies would increase the very climate change that’s exacerbating the 1,200-year drought afflicting the Colorado River in the first place, said Newman, who in his previous job helped the state of Colorado design a long-term water conservation plan. At comment sessions on Colorado's plan, he said, long-distance pipelines were constantly suggested by the public.

"Sometimes there is a propensity in areas like Louisiana or the Southwest, where we've had such success in our engineering marvels, to engineer our way out of everything," Newman said. "I don't think that drought, especially in the era of climate change, is something we can engineer our way out of."

'Arizona really, really wants oceanfront'

But big water infrastructure projects aren't just of interest to the general public.

Arizona, which holds "junior" rights to Colorado River water, meaning it has already been forced to make cuts and might be legally required to make far larger reductions, wants to build a bi-national desalination plant at the Sea of Cortez, which separates Baja California from the Mexican mainland. The resulting fresh water would be piped north to the thirsty state.

Such major infrastructure “is an absolute necessity,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, who said he “represents the governor on all things Colorado River.”

Arizona's legislature allocated $1 billion in its last session for water augmentation projects like a possible desalination plant, and state officials are in discussions with Mexican officials about the idea, said Buschatzke.

The state also set aside funds in 2018 to study possible imports from the Missouri or Mississippi Rivers, but to date, the study hasn’t been done, he said.

Others said the costs of an Arizona-Mexico desalination plant would also likely prove infeasible.

"The desalination plant Arizona has scoped out would be by far the largest ever in North America," said Jennifer Pitt, National Audubon Society's Colorado River program director.

Pitt, who was a technical adviser on BLM's 2012 report, decried ceaseless pipeline proposals. "Nebraska wants to build a canal to pull water from the South Platte River in Colorado, and downstream, Colorado wants to take water from the Missouri River and pull it back across Nebraska. It boggles the mind. I can't even imagine what it would all cost."

'CLEAR THE LAKE IS IN TROUBLE': Great Salt Lake breaks record low level for the second time in a year amid drought

Westford, of Southern California's Metropolitan Water District, agreed. "Arizona really, really wants oceanfront," she chuckled.

But Westford and her colleague Brad Coffey contend desalination is needed in the Golden State. Despite the recent defeat of a major plant in Huntington Beach, after the California Coastal Commission said it was too environmentally damaging, "ocean desalination can't be off the table," said Coffey, a water resources manager.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom also touted desalination in a drought resilience plan he announced last week, though in brackish inland areas. All three officials said the construction of a 45-mile Delta Water Project tunnel to keep supply flowing from the middle of the state to thirsty cities in the south is vital. That project, which also faces heavy headwinds from environmentalists, would cost an estimated $12 billion.

Coffey said the project isn't really a pipeline, but more "a bypass for ... an aging 60-year-old" system.

Is this the time for a national water policy?

So what are the solutions to the arid West's dilemma, as climate change heats up and water resources dry up due to reduced snowmelt and rainfall?

Global water scarcity expert Jay Famiglietti said it's time for a national water policy, not to figure out where to lay down hundreds of pipes but to look comprehensively at the intertwining of agriculture and the lion's share of water it uses.

For him, that includes setting aside at least portions of the so-called "Law of the River," a complicated, century-old set of legal agreements that guarantees farmers in Southern California the largest share of water.

"Should we move the water to where the food is grown, or is it maybe time to think about moving the food production to the water?" said Famiglietti, a University of Saskatchewan hydrology professor who tracks water basins worldwide via NASA satellite data,

In southeastern California, officials at the Imperial Irrigation District, which is entitled to by far the largest share of Colorado River water, say any move to strip their rights would result in legal challenges that could last years. General Manager Henry Martinez also warned that cutting water to Imperial Valley farmers and nearby Yuma County, Arizona, could lead to a food crisis as well as a water crisis.

Martinez, an engineer who oversaw the construction of pipelines in the Sierra Nevada for Southern California Edison, agrees a 1,500-mile pipeline from the Mississippi could physically be built.

But, he said, the days of mega-pipelines in the U.S. are likely over due to lack of environmental and political will.

Janet Wilson is senior environment reporter for The Desert Sun, and co-authors USA TODAY's Climate Point newsletter. She can be reached at jwilson@gannett.com or @janetwilson66 on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Climate change has dried the West. Could a pipeline be the answer?