'The perfect target'? Movement to ban books from schools brings vitriol toward librarians

When Amanda Jones saw that her local library board in Livingston, Louisiana, would be discussing “book content” at a meeting in July, she knew she had to speak up. Conservative activists in the state had called for removing certain young adult nonfiction books from children’s shelves, and Jones, a middle-school librarian, worried they were gaining traction in her community.

The titles in question, including “Dating and Sex: A Guide for the 21st Century Teen Boy,” aim to teach young readers about topics such as reproductive health and romantic relationships, sometimes through illustrations of genitalia or people having intercourse. Most of them also include LGBTQ characters or themes.

Jones told the board she was a librarian, without naming her school, speaking about the detrimental effects of relocating books from the children who might need them the most. More than 15 other community members similarly warned against such restrictions. A much smaller number of speakers testified in favor of moving the books to the adult section. The board ultimately decided to keep the books where they were.

Jones thought – or, at least, hoped – that would settle things. Then images started appearing on social media. One identified her as a school librarian, her face circled in red. “After advocating teaching anal sex to 11-year-olds I had to change my name on Facebook,” she said another read. Some commenters called Jones a “pervert”; one, a “sick pig.” A few concluded that Jones needed to be fired or slapped.

Jones, the only self-identified librarian to testify at the July meeting, said her district recently received requests from the same activists for her disciplinary records and email history, as well as a list of every book in the campus library. “Now they’re attacking me at school for speaking out at a public library meeting,” said Jones, who was the School Librarian Journal’s 2021 national librarian of the year and is president of the Louisiana Association of School Librarians.

“These people like to pick the strongest link in the room and attach to that person and hope they can take them down so that everyone else will be quiet,” she said. “I was the perfect target.” Jones recently sued two of the activists for defamation and said she’s committed to staying on the job.

Librarians, in schools and communities, remain widely popular, viewed as some of society’s most trustworthy members, recent polling shows. But they have become targets of a new front in the culture wars over what and how to teach children about race and sex. A vocal minority has denounced them as woke social justice warriors with a radical agenda to indoctrinate children or as pedophiles with a perverted mission to “groom” children into victims of sexual abuse.

Rates of harassment against educators, including librarians, have risen, coinciding with a record-high number of book-banning efforts. The American Library Association tracked 729 challenges to library, school and university materials and services in 2021, the most since the organization began documenting them two decades ago. Amid the outrage, some librarians have been fired; others have quit. Many others remain dedicated to their jobs, but they aren’t sure how much more they can take, several told USA TODAY.

Observers fear the viral – and visceral – nature of the accusations, combined with this year's election cycle, signals an even more hostile climate this school year. The tensions extend to regular public libraries, too, over those librarians’ attempts to provide a broad range of reading material. Some worry the hostility will continue to push librarians, existing and prospective, out of the field. The number of school librarians has plummeted over the past decade, partly because of budget cuts, a trend that only became more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

'We are war moms': Moms for Liberty dominates school board politics across US

Challenges to books and librarians have been coordinated over the past year.

Moms for Liberty, a group of parents’ rights activists with chapters across the country, has an offshoot initiative called Moms for Libraries. The campaign seeks to get books with conservative perspectives into public school libraries, such as former Trump administration Cabinet member Ben Carson’s “Why America Matters.”

Other challenges go a step further. Staff at public libraries have been accused of infringing upon parents’ rights, and legislation in a few states would subject them to criminal charges for stocking certain books.

In Jamestown, Michigan, voters chose this month to defund the local public library amid controversy over LGBTQ-themed books. In Victoria, Texas, government officials threatened to evict the public library from its building this month unless it removed certain materials. And in several high-profile incidents this summer, activists affiliated with the extremist group Proud Boys disrupted Drag Queen Story Hour events at libraries.

“When we’re asked for help finding materials, we gladly give it,” said Martha Hickson, a school librarian in New Jersey who was harassed and questioned after refusing to remove controversial books from her library’s collection. “Sometimes we’re being asked to provide the ammunition for the gun that’s going to be aimed at us.”

So as excited as librarians may be to reunite with students in person, they begin the semester with “a little trepidation – like, am I going to be personally attacked?” said Kathy Lester, president of the American Association of School Librarians. “Some of the things that people are saying really are so hurtful because we would fiercely protect our students.”

‘I’m kind of at the end of my rope’

Book challenges and library controversies are nothing new, but never before has the backlash gained this kind of traction or led to such personal attacks, librarians said.

"I have not seen anything like this in my lifetime," said Becky Calzada, district library coordinator in Leander, Texas. "There are problems being created where they didn't exist."

After a Texas lawmaker distributed a list of 850 books last fall that he wanted reviewed for possible removal from campus shelves, Calzada and two other school librarians in the state co-founded a group called the FReadom Fighters with the idea of pushing back against such efforts in campus libraries.

Districts across Texas have been navigating book challenges, in some cases deciding to skim certain titles off their collections. In Calzada’s own district, a group of parents succeeded last winter in securing the removal of nearly a dozen books from high schoolers’ optional-reading lists.

Most of the clashes are taking place in conservative areas, like in the roughly dozen states where lawmakers have recently considered or passed legislation restricting librarians, some by limiting or tracking what children search for in school library databases. But incidents are bubbling up in blue states, too.

Book bans are on the rise: What are the most banned books and why?

Hickson is a veteran school librarian in New Jersey. Like Jones, she says she was singled out – in her case last fall, for stocking and defending books including “Gender Queer: A Memoir” and “Lawn Boy,” both of which feature LGBTQ relationships. As with Jones, she was labeled a pedophile and a groomer. And similar to Jones' case, public-records requests were filed seeking information such as her library’s entire purchasing history.

“The best way to describe (what I felt) would be mortified,” said Hickson, who added that she received hate mail and was the subject of pranks by students in favor of prohibiting the books. “Those kinds of allegations can be career-ending for an educator.”

One day last October, after weeks of harassment, she ended up at the school nurse’s office crying, with searing pains in her stomach, she says. Her blood pressure, usually in a normal range, was through the roof; she could barely breathe, let alone talk. Hickson, 62, was eventually diagnosed with an ulcer, took medical leave and began seeing a therapist twice a week.

Hickson returned to school last winter, and while scores of community members rose to her defense last school year, she worries that they’ve since lost their momentum. “I go back to school in three weeks and I’m dreading it,” she said this month. “I truly, truly love my work, but I’m kind of at the end of my rope.”

More: Texas mom’s campaign to ban LGBTQ library books divided her town – and her family

Have librarians gone overboard?

Critics say librarians have gone too far in their efforts to be inclusive.

Michael Lunsford runs Citizens for a New Louisiana, a government watchdog nonprofit, and is one of the activists who has called out Jones and other library leaders. He’s named as a defendant in Jones’ suit.

Before that July library board meeting, Lunsford said, he learned that books about sex were available in the children’s section of the public library in Lafayette. Appalled, he began submitting requests that they be removed or relocated; eventually, he was informed that the director had already decided to move one in particular to the adult section.

Lunsford agreed it was a good solution. He was shocked when the library in Livingston, more than 100 miles east, refused to do the same.

Lunsford said the push to move the books had little to do with the fact that they had LGBTQ content. Rather, it was that they included graphic images of naked people, including of them having sex and masturbating. Children “shouldn’t be able to find (that book) sitting next to ‘The Cat in the Hat,’” said Lunsford, who declined to comment on the lawsuit. The books, classified as young adult, however, were in a section aimed at 12- to 18-year-olds.

He attributed some of the problem to libraries’ reliance on review journals when determining what books to add to their collections – a practice that has gained attention in conservative circles.

Susan Anderson, library director in Redondo Beach, California, recently analyzed the political leanings of books featured in review journals and found a clear bias toward books by progressive authors.

Anderson said she makes a concerted effort to include books that are bestsellers, including many by right-leaning writers that haven’t been reviewed in the standard journals.

“It’s much easier to defend keeping (a certain book in) if you can honestly say you collect materials from a wide range of viewpoints,” Anderson said.

School librarians say that’s precisely what they’re trying to do.

Every year, Debra Quarles, head librarian at Shaker Heights Middle School in Cleveland, carefully curates a recommended reading list for students. Students at Shaker Heights Middle have diverse interests and maturity levels, and that diversity is something Quarles embraces as a librarian.

But it also puts her to the test, particularly when it comes to reading recommendations: “While I’m dealing with trying to find this nice middle ground, I have parents who say, ‘No, this is way too mature,’ and then I have parents who say: ‘You know, you really aren’t pushing kids enough. They need to have more authenticity.’”

These days, Quarles is extra-careful when she compiles the reading list, making sure to provide alternatives for parents who want them and not to go overboard in pursuit of diversity. For example, she recently reviewed the cover art for books she was considering for the list and realized none featured white males. She replaced one of the titles with a book about a white boy who likes to cook.

In her 25-year career as a librarian, Quarles has dealt with only four formal book challenges, and the discussions for all of them remained civil. But Quarles isn’t sure how long that will last – especially in a conservative-leaning swing state like Ohio.

“For those of us who are already in librarianship, how long do we want to keep doing this?” Quarles said. “When is the fight going to come and sit on my doorstep?”

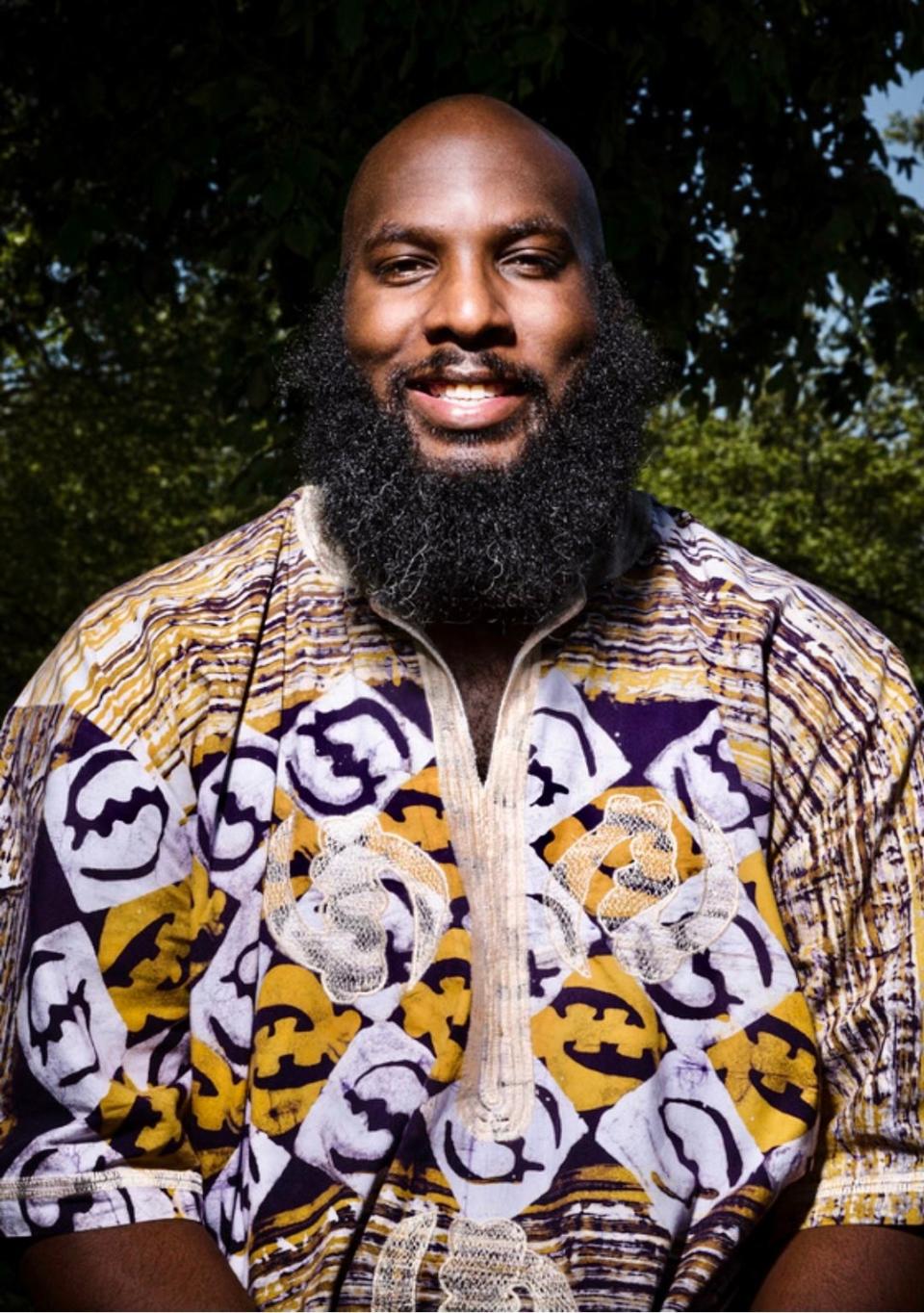

It’s librarians’ responsibility as educators and public servants “to make sure that we are serving every student, parent, guardian, educator, community member with opportunities galore,” said Christopher Stewart, a librarian at a public high school in Washington, D.C.

Stewart said debates over who’s most in need of those opportunities, and what that opportunity looks like, are productive in that they’re forcing librarians to wrestle with that responsibility and what it means in this era. “It’s an uncomfortable space to navigate, but it’s also necessary,” he said.

School librarians dwindling

The political pressures threaten not only to have a chilling effect on library collections but also on whether librarians stick with the profession.

“Is it causing librarians to question themselves? Yup, because they see what’s happening,” said Calzada, the school librarian in Texas, who helps peers navigate book restrictions. “It just takes one thing to decide ‘I can’t take it anymore.’”

As it is, just 26 states have explicit policies requiring that every school employ at least one school librarian, according to Debra Kachel, who teaches school librarians-in-training at Antioch University Seattle, and most of them are no longer enforced. Kachel and Keith Curry Lance, a Colorado-based school library consultant, have been studying trends in the field over the past decade and through the pandemic. In the 2020-21 school year, they found, 30% of the country’s school districts didn’t have a single school librarian.

Their research also revealed that the number of school librarians has been shrinking for years: Over the past decade, the number of librarians has plummeted by 20%. The number of universities offering master’s degrees in library science has dropped, too.

Texas: School district pulls over 40 books, including the Bible, from shelves

Fights over book collections could persuade school leaders to deprioritize or cut library budgets, including for potentially controversial books, experts said, which would build on a shift made because of COVID-19.

Data from Kachel and Lance show that of the districts that lost librarians during the pandemic, half gained new teachers, and one-third gained administrators.

School librarians “know they are devalued. They’re saying, ‘I can’t stay in this role because I don’t know if I’m going to have a job next year,’” Kachel said. “So we do see a lot of librarians leaving, maybe taking classroom positions or just getting out of education altogether.”

And when librarians leave, she said, seldom are they replaced.

The declining numbers hurt disadvantaged students most. A body of research suggests librarians have a strong influence on student achievement – schools that have them have higher graduation rates than those who don’t, for example. Yet low-income schools and those with high concentrations of students of color tend to lack access to librarians, according to studies by Kachel and Lance.

One of their analyses found that majority Hispanic schools are twice as likely as those that are majority white to lack a school librarian. And majority Black districts were almost twice as likely as other districts to report pandemic-related librarian losses.

Advocates say the rising number of book challenges underscores the need for school librarians – people who are trained in the vetting and selection of materials who can speak to concerned parents about the decision-making process.

“Librarians are almost digging deeper and reestablishing what drew them to this in the first place,” said Nicolle Davies, assistant commissioner of the Colorado State Library. “It’s a really challenging time to do the work we do. But it’s also more important than ever to do the work we do.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Book bans in schools have landed librarians in activists' crosshairs