Parents Not So Thrilled About Most K-12 COVID Recovery Plans

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

After more than a year in which the majority of students attended school fully or partially remotely, districts nationwide are contemplating how to meet children’s present academic and social needs and prepare them for the 2021-22 academic year. A slew of policies and practices are on the table for the summer and coming year, bolstered by funding from the American Rescue Plan.

One crystal-clear lesson from the ongoing crisis of school hesitancy has been just how influential parents are in determining their children’s educational pathways. Education leaders must factor in parents’ perspectives, or reopening can be a flop — students won’t show up. So we asked the Understanding America Study‘s nationally representative sample of approximately 1,500 K-12 parents how they feel about a range of practices and policies under consideration. Many of the results are surprising.

Parents’ enthusiasm for in-person summer school, tutoring or pods is limited

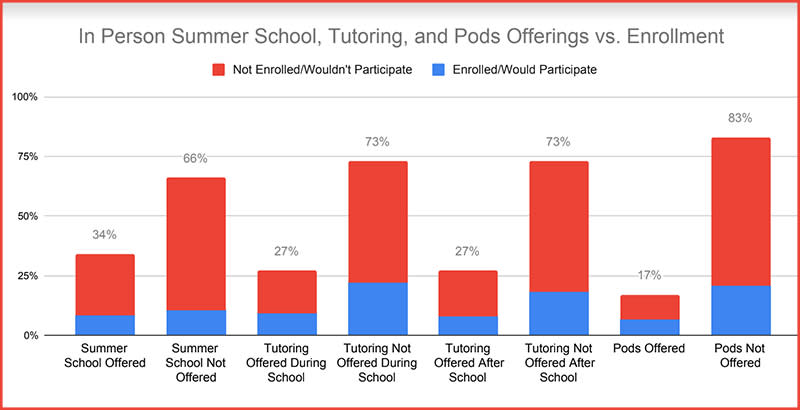

Among the top in-person interventions that researchers are recommending and districts are considering, summer school, in-person tutoring during and after school, and learning pods are high on the list. We asked parents whether their school currently offers each of the four interventions, whether their child is or will be participating if the school is offering, and if the child would participate if offered.

For in-person summer school, as of the end of May, a third of parents (34 percent) report their child’s schools were offering, a quarter of those whose schools had offered had enrolled (25 percent) and just 16 percent of those whose schools were not offering in-person summer school say they would participate if offered.

Related: Learning Hubs: A Shovel-Ready Strategy for Spending New Federal Relief Funds

The picture is similar for during- and after-school tutoring held in person. Roughly a quarter of parents say their school offers in-person tutoring (27 percent both during and after), and of that quarter of parents, 34 percent of their children participate during school, 29 percent after. Among those who don’t currently have the opportunity, 30 percent of parents say they would enroll their child for during-school tutoring, 25 percent after-school.

In-person pod use is also low, with 17 percent of parents reporting their child’s school offers pods. Of those, 38 percent of students are participating. If offered, 25 percent of parents say they would enroll their child in a pod.

Though proportions of parents indicating interest in in-person summer school, tutoring and pods are likely higher than pre-pandemic, they still indicate a limited audience for each now, when districts are pouring resources into these types of interventions.

Parents do not support more instructional time or most other policies under consideration

We also asked parents about their support for a range of policies meant to address negative learning effects of the pandemic, including increasing instructional time, and changing grading and grade-level promotion policies. The only policy with majority parent support was providing students the option to repeat the 2020-21 grade level, with 64 percent supporting or strongly supporting. However, this policy had significantly less support among Black (51 percent) and Hispanic (58 percent) parents than white (70 percent), less support (25 percent) among parents at the lowest-income level (less than $25,000 a year) versus the highest (greater than $150,000, 78 percent), and among parents with less education (60 percent among those with a high school diploma or less) versus 71 percent of those with at least a bachelor’s degree.

Only a minority of parents supported other policies we suggested on the survey, including use of pass/fail rather than A-F letter grades (29 percent), longer school year/shorter summer vacation (23 percent) and longer school days (19 percent). The least popular option was to promote students to the next grade even if they don’t meet the requirements (15 percent).

Parents want to continue to harness technology — including for tutoring

One area where we did find substantial support was for various technology-related policies. Though most parents do not favor tutoring overall, remote tutoring scored high in the survey, with 82 percent of parents supporting or strongly supporting. This is consistent across subgroups. Parents also want to use remote means for parent-teacher conferences (80 percent) and for students to communicate with their teachers (e.g. email, 75 percent). They want to use online platforms like Canvas or Google Classrooms to store, organize and distribute class materials (73 percent) and pivot to remote school when the weather is bad or schools need to be closed for another reason (73 percent). The majority also want students to be able to submit assignments (63 percent) and read (59 percent) online. Half of parents support allowing students to work on their own time, without a teacher physically present (50 percent).

Implications

First, the good — parents feel several features of remote education are useful and should remain part of their children’s K-12 education. There was particularly wide support for remote tutoring, relevant given policymakers’ preferences and research evidence in support of tutoring as a key solution for helping students to get back on track emotionally and academically post-pandemic. Widespread device dissemination through the past year, as well as increases in internet access and quality provided for under the American Rescue Plan, greatly enable remote tutoring and other online features parents like.

Then, the challenges — many of the results suggest ambivalence among parents about the COVID-19 recovery agenda, echoing that found among teachers. There is especially tepid support for increased learning time, for which research evidence demonstrating effectiveness is uncertain. There is also limited unmet desire for in-person tutoring and other in-person remediation policies popular in the research-and-policy crowd. Summer school, tutoring and pods may be effective in research settings, but they won’t work in person at scale unless people participate. This may mean helping parents understand the benefits for their children, or it may mean that parents and children are simply too exhausted and need the summer off to recover.

What these results make clear is that education leaders need to talk to parents to figure out what programs and policies they would support and participate in before simply creating COVID-19-relief programs using rescue plan dollars. Otherwise, participation may be far too weak to really move the needle on students’ academic and social/emotional needs.

Anna Rosefsky Saavedra is a research scientist at the University of Southern California Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research. Morgan Polikoff is an associate professor of education at the USC Rossier School of Education. He studies standards, assessment, curriculum and accountability policy.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation Grants No. 2037179 and 2120194. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.