An orphaned teen is stuck in London. Will her aunt, uncle be able to get her to Charlotte?

If you didn’t know any of the backstory, it’d be easy to walk into 16-year-old Pramiti Taranikanti’s bedroom and assume she has been living a pretty good, pretty stable, pretty happy life in south Charlotte.

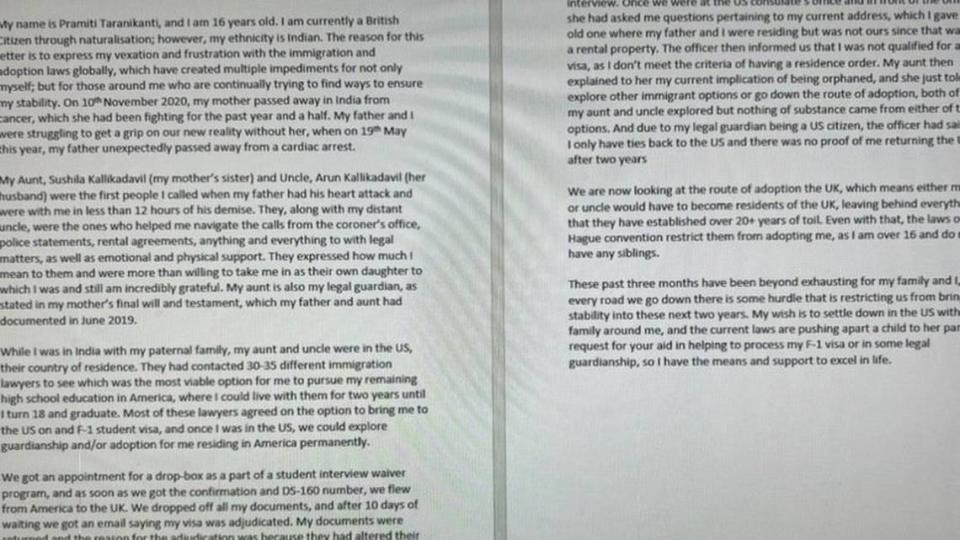

There are photos of a smiling middle-aged couple — her parents — hanging in opposite corners of the room. Two guitars — one electric, one acoustic — lean up against the wall near the closet. And on the desk by the window, a letter dated July 11 opens with a congratulatory tone: “I would like to take this opportunity to welcome your family to Providence Day School. ...”

Get Pramiti’s aunt and uncle to fill in the blanks, though, and the illusion of stability and contentedness in the teen’s life quickly evaporates.

The pictures in the corners, they explain, serve more as memorials than mementos; Pramiti’s parents died a year and a half apart, her mother in November 2020 after a long battle with cancer and her father of sudden cardiac arrest just this past May. The guitars, which doubled as stress-busters when she was grieving her mom’s death, haven’t been regularly played by Pramiti in months.

As for her acceptance to Providence Day? She’s since been forced to withdraw — a development that, in the overall scheme of things, would seem rather minor.

That is, until Arun Kallikadavil and Sushila Rayaprolu explain the overall scheme of things.

Pramiti’s parents, Satyamani Rayaprolu (Sushila’s sister) and Srikanth Taranikanti, left specific instructions stating that, in the event of their deaths, they wanted Sushila and Arun to become Pramiti’s guardians. So, shortly after her dad’s death, Sushila and Arun started getting a spare bedroom ready for their orphaned niece.

Yet four months later, it remains empty.

Pramiti is currently stuck 4,000 miles away, in London, and in spite of the fact that her aunt and uncle spent the summer trying to cut through bureaucratic red tape to bring Pramiti to Charlotte, so far, all they have to show for it are a big pile of her shipped-over belongings.

And a mountain of frustration.

“Every time (we talk to her) she asks the question, ‘When am I coming home?’ And it breaks us apart,” Arun says. “I’ve never felt this helpless in life.”

‘I need you here right now!’

Pramiti’s mom was a fighter.

She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2017 and treated successfully in 2018, had a recurrence in January 2019, then told by doctors there was nothing more they could do early the following spring. Not long after that, she entered hospice care and was transported from the U.K. to India, because she wanted to live out the final days of her life with her parents.

Those days turned into months, then — even as the cancer spread to her brain and her liver — more than a year.

She set a goal of hanging on until Pramiti turned 16 but fell six months shy, finally succumbing on Nov. 10, 2020, after she was spoon-fed her last meal by Pramiti and Sushila.

Just over three weeks later, urged on by Pramiti’s father, her aunt and uncle took the Naturalization Oath of Allegiance to the U.S., after having lived here for almost 20 years as Indian citizens. (“‘She would want that,’” Arun remembers his brother-in-law telling them.) Because the Indian constitution forbids dual citizenship, on the same day, they surrendered their Indian passports.

Right after that, at Christmastime, Pramiti came to Charlotte to visit her aunt and uncle, at which point they expressed interest in traveling to London to celebrate her 16th birthday on May 1. But when an unexpected opportunity arose in late April for Arun and Sushila to travel back to India to visit his parents, whom they hadn’t seen since before the pandemic, they tabled the idea of visiting Pramiti and her father in the U.K. until the summer.

Just 18 days after Pramiti’s birthday, Arun received a frantic call from Pramiti. “‘He’s not breathing!’” Arun recalls her shouting. “‘I need you here right now!’”

By the time emergency personnel arrived, he was gone.

The next week and a half or so was a blur of shock, grief and paperwork across countries, as it proved to be a logistical nightmare of sorts getting Pramiti’s father’s body from the U.K. to India so he could be given the traditional Hindu funeral rites.

That was nothing, though, compared to the headaches to come.

‘No matter what, I will be with them’

It seemed like a foregone conclusion to Pramiti that she would wind up with her aunt and uncle.

“We were incredibly close growing up,” she says, via a video call from London. “At least once if not twice a week we would call at length for at least an hour or so. We would just talk about everything and anything. They were like my best friends.

“I mean, I think deep down in the back of my mind, I was like, ‘No matter what, I will be with them.’”

And there are alternate scenarios in which she would be, already, at this point.

For instance, if Pramiti’s father had died when she was 15 (or if she was a big sister), there would have been a smoother path for Arun and Sushila to adopt their niece. However, for Pramiti to be eligible for adoption via the Hague Convention process, she would have needed to be younger than 16 at the time the petition to adopt was filed. (From 16 to 17, it’s possible — if you have a younger sibling; but Pramiti is an only child.)

Furthermore, if Arun and Sushila had held off on obtaining their citizenship in the United States, it might also have been a nonissue. India’s adoption laws are not as restrictive.

As a result of their U.S. citizenship, though, by the end of May it had become clear that adoption was off the table.

The focus shifted to simply trying to get her to Charlotte by any legal means possible, before the start of the new school year. But at every turn, it seemed, Arun and Sushila’s efforts to bring their niece here on a more permanent basis were blocked by the U.S.’s inflexible immigration laws.

To make a very long story short, they would come to learn that their best chance was to bring Pramiti over on an F-1 visa, which allows international citizens to enter the country as full-time students. Although there is a 12-month cap on stays for foreigners studying at a public high school, there is no limit at private schools like Providence Day, the school that admitted Pramiti and issued her the documentation required for a non-immigrant student visa application.

The family felt confident that it would sail through.

Arun, in fact, flew to the U.K. in late July in anticipation of returning with her. But her application wasn’t addressed as quickly as they’d hoped, and in early August he had to get back on a plane — without her.

‘Why are we depriving the child?’

A week later, the U.S. Embassy in London notified the family that a visa had been denied.

Sushila flew back across the Atlantic the following week and took Pramiti to a follow-up appointment with a consular officer, who told them the visa was refused because they didn’t show Pramiti had strong ties back to the U.K. In other words, the concern was that she would stay in the U.S. after graduating from high school, and on paper at least, the government wanted to prevent that from happening.

So — and again, a very long story made very short — Arun and Sushila submitted 180 pages of documents that they felt showed she would return to the U.K. once she graduated from Providence Day and applied for the F-1 visa, again.

It was denied, again.

“Today’s decision cannot be appealed. However, you may reapply at any time,” a consular officer wrote in an August letter, which the family shared with The Charlotte Observer. “If you choose to reapply, you should be prepared to provide information that was not presented in your original application, or to demonstrate that your circumstances have changed since that application.”

Arun shakes his head in disgust as he talks about it.

He calls the requirements to meet the threshold “stupid.” The government would count owned property as a tie, he says, and her parents bequeathed some to her — but she can’t legally own it until she’s 18. It would count a college acceptance, but she can’t enroll at a college in the U.K. this prematurely. And for obvious and very sad reasons, Pramiti isn’t able to prove that she has family ties that would bring her back.

“So we are in limbo,” Arun says.

“Why?” Sushila says, as her voice starts to break. “Why are we depriving the child of the simplest thing that she’s asking of? I will understand that if there are no other means, nothing. But we are here. My sister thought that I will take care of her, and I’m unable to do that. ... You know? What am I going to answer to my sister? That, ‘Oh, I can’t take care of your child?’ Only because I have these impediments? Or these laws that are coming in the way of me to take care of the child?

“That’s the worst feeling for anyone to have.”

‘Not left with any other options’

No one in the family feels anywhere near settled.

Pramiti has been staying with the family of her best friend, and every day she feels like an imposition. Sushila, a high school math teacher for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, says she has been in discussions with the district about some sort of long-term leave of absence. A decision is pending.

If CMS will hold her job for her, she plans to relocate to London temporarily so Pramiti can live with her — although that creates a whole set of new challenges, since Sushila is not a U.K. resident and would have to get creative to legally inhabit an apartment there. (Sushila could stay six months on a U.S. passport, but any longer would require her to obtain a work permit.)

If CMS won’t hold her job for her ... she may have no choice but to quit.

Arun, meanwhile, is employed as head of commercial banking data at Wells Fargo and couldn’t easily find an equivalent position in England. Even if they could, they don’t want to leave their son, Ashray, a junior at UNC Chapel Hill, all by himself in the U.S.

The stress has been all-consuming. Arun and Sushila both say they haven’t slept more than about three hours a night since May.

In fact, they’ve become so irritated, discouraged and exhausted by the whole process, Arun says, that they’ve fantasized about bringing her into the country through the Electronic System for Travel Authorization system, and just not abiding by the limits. (Known as “ESTA,” it’s part of the U.S.’s Visa Waiver Program and is generally valid for multiple business or pleasure visits — a “reasonable” amount of them, up to 90 days at a time — over the course of two years.)

“I was telling Sushila the other day, ‘Maybe we just should do that,’” he says. “Because we are not left with any other options. ‘Maybe we should just do that.’ I mean, that’s how frustrated we are.”

He then clarifies. “We won’t. But it’s a feeling.”

Asked who he feels most let down by, Arun doesn’t hesitate. “Our country. Our laws,” he says. “And more importantly and unfortunately, someone who was doing their job based on a checklist and not applying some amount of empathy and compassion. I get the checklist. It’s important. But —”

He shakes his head again, throws up his hands, and sighs.

Yet despite their anger and their disappointment, despite the fact that every day seems to bring another piece of vexing news, or another dead end, they haven’t given up.

‘When is this all gonna end?’

Since July, Arun says, they’ve been in contact with an immigration specialist in North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis’s office who has monitored their case and been in communication with the U.S. Department of State on their behalf. It hasn’t yet helped much. (A spokesperson for Tillis confirmed Wednesday by email that the senator’s office has been in contact with the family, but declined comment “due to confidentiality rules regarding constituent casework.”)

Still, Arun and Sushila cling to hope that his office, or Tillis himself, eventually might be able to help get Pramiti here.

In lieu of that, they’re still hopeful that they’ll soon find an immigration lawyer who comes up with an idea for a solution that the other 30-plus they’ve consulted have not. Or, that maybe the Change.org petition they started can make a difference; it’s at just over 8,000 signatures, but they dream of it eventually reaching 100,000, which they think will get them noticed.

They’re also still, of course, talking to their niece every day. Still trying to give her all the love and support she needs, like her parents would, if they were still here.

And though she’s really still just a kid — as you can tell by the stuffed animals arranged at the head of the bed in the room her aunt and uncle someday hope she’ll finally move into — Pramiti sounds pretty grown-up when she says things like this:

“The overwhelming thought right now, I guess, is just frustration and kind of desperation, as well. ’Cause it’s like, ‘When is this all gonna end?’ I mean, there’s no secret that I’ve been through a lot over these past few years, and so have the people surrounding me. And I’m just wondering, ‘When will life stop testing us and putting us in these impossible situations that we can’t seem to get out of?’

“I pray every day, and I hope — hope that something will work out.”