A doctor explains 'the most surprising thing' about America's opioid crisis

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

This is part 3 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the big business behind opioids in the United States. Listen to the series here.

Opioid overdoses have taken tens of thousands of American lives over the last decade.

“The biggest thing here is everyone probably has in their mind the picture of who they think is overdosing,” said Dr. Ryan Marino, an emergency room physician and medical toxicologist. “And that’s reinforced by what our society teaches us about people that use drugs and movies and TV.”

Marino explained that “the people who overdose and who use drugs in general are not some bad element of society. They’re not always vagrants and people who are choosing, making bad choices, for lack of a better way to say it.”

“It’s really something that affects everyone,” Marino continued. “I’ve seen young kids. I’ve seen elderly people. I’ve seen people from the best families, people from the worst families. It’s really something that affects everyone, and I think that’s the most surprising thing.”

One of those deaths happened to Cheryl Juaire’s son, Corey. After he overdosed on heroin, Cheryl suffered a grief like never before.

“I cried a lot,” Juaire said. “I suffered in my grief a lot. I’m originally from Massachusetts, so we decided to move back home. My son was buried up here and I was flying up every three months, so it just made sense to come home. I joined a couple of groups on Facebook.

“And through that, one night, this mom reached out to me and she sent me a message and says, ‘I know this is last minute, but tomorrow night there are six of us moms going out to dinner and would love to have you come, and we’re all from Massachusetts.’”

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season three: The United States of Opioids: Behind a uniquely American crisis

She had found a place where other people understood the emotions she was feeling, and knew she wasn’t alone.

“There were seven of us and we pretty much closed that restaurant,” she said. “We laughed, we cried, we shared stories. We shared things that I thought at one point I wanted to die because the pain from my grief was so bad from losing my child. I wasn’t going to kill myself. I just didn’t want to live anymore with that pain. And I found out they all felt the same way. So I was like, ‘I guess this is normal.’”

“One of the things that we discussed at the table was over time, people forget our child,” Juaire said. “They forget their date of birth and their date of death. And with us, it’s something we’re never going to forget ever. And only we knew that and only we felt that way. So when I created the group, it was just for us seven and I said, ‘Okay, so you need to give me your child’s name, their date of birth, and date of death, because in this group we’ll never forget it and I’ll always make sure we remember.’”

‘The stigma is still alive’

Cheryl and her six friends were the founding members of Team Sharing, which has become a national organization with 16 state chapters to help grieving families who have lost someone to substance use disorder.

“There are so many people out there walking along like a zombie like I did, that for me, my goal is to reach out and have a chapter in every state,” Juaire said. “But the stigma is still alive.”

For parents who have lost a child to addiction, people often “look down on you,” Juaire explained.

“Your child died from an overdose? He must’ve been a bad kid,” she said. “You must’ve raised him wrong. You must’ve done something wrong. And that’s the mentality of thinking unless it’s touched them, unless they know somebody, they’re just going to be ignorant to it. Unless they come and say, ‘Tell me about that loss. What happened?’”

Juaire shared of one parent who lost his son to an overdose, but is telling everyone he died from a heart attack because of “complete denial.”

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season three: The United States of Opioids: Behind a uniquely American crisis

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

Transcript:

Adriana: You've probably heard it before. Drug addiction is a choice. Those with substance use disorder should be in jail. We shouldn't even consider decriminalization or harm reduction. These are just some of the common notions that are floated by everyday Americans when it comes to addiction. But what if these beliefs are actually doing more harm than good? This is the third and final episode of Illegal Tender season three. I'm Adriana Belmonte.

Ben Westoff: What's scary about fentanyl is that it's a drug most people don't want.

Adriana: Ben is a journalist and the author of Fentanyl, Inc.

BW: When it comes to drugs that are killing people like heroin and cocaine, the users tend to want this. But nowadays, young people who are buying drugs off the Internet, street level users, people of all ages and demographics are susceptible to fentanyl because they think they're getting other drugs.

BW: And the way that the singer Prince died was that he thought he was taking a legitimate pharmaceutical pill, an opioid for pain. But it was actually cut with fentanyl. That's the same with Tom Petty and the rapper Mac Miller. And so increasingly, we're finding fentanyl being cut into these black market, be it Oxycontin, Valium, or excuse me, Vicodin, Percocet. And so these pills look exactly like the real thing.

Adriana: As a medical toxicologist, Ryan Marino sees this in his everyday work. When was it that you saw fentanyl was becoming a major issue?

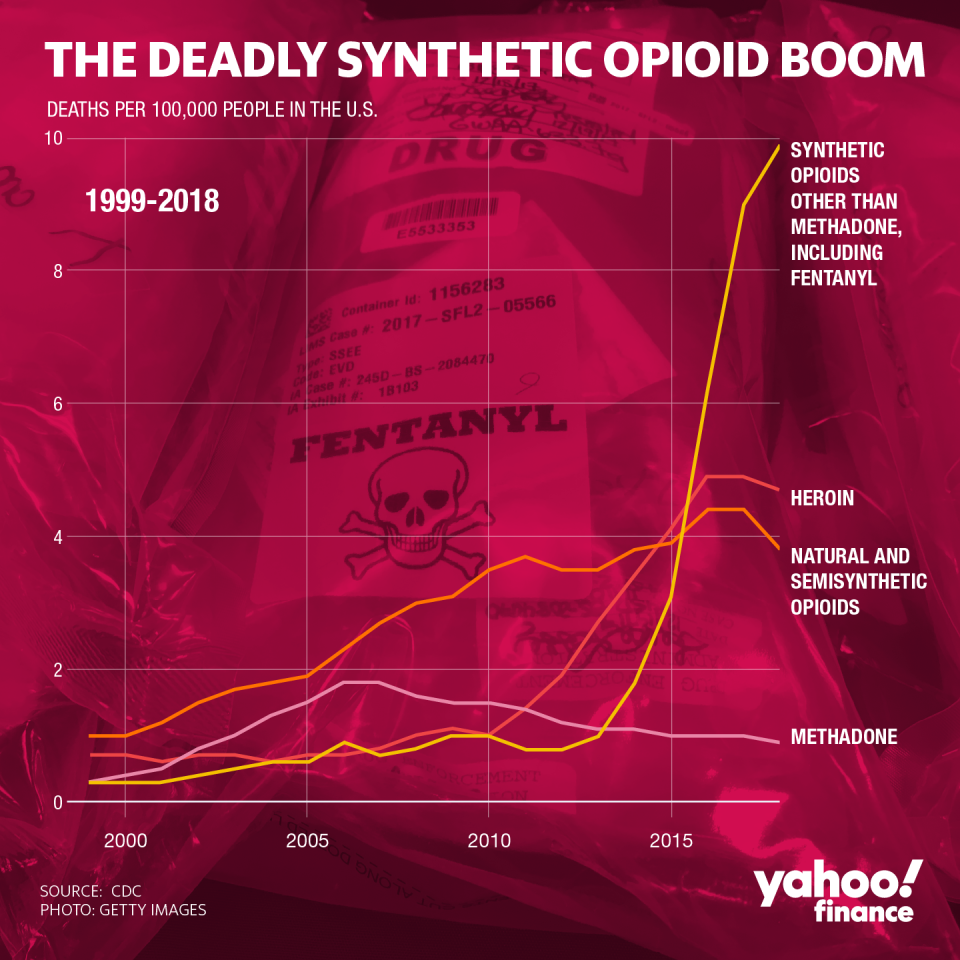

Ryan Marino: Probably around like 2015 or so. It started showing up more and more and kind of by, I think around 2017, where I was at the time in western Pennsylvania, it was pretty much all fentanyl in what was sold as street heroin, and kind of the other synthetics have replaced what was previously heroin being sold on the street, but primarily fentanyl.

Adriana: I'm curious, I often see a lot of times just in the media, they kind of go back and forth between referring to this as a fentanyl crisis, a fentanyl epidemic, opioid crisis, opioid epidemic. What is the right term that should be used to describe what's going on right now around the country?

RM: Yeah. Opioids get a lot of attention and the opioid epidemic is kind of the buzz phrase everyone hears, but I refer to it as an overdose crisis, because I think the real crisis is just that people are overdosing. The rates of opioid use have not really gone up that significantly within the past few years. The rates of prescription opioid and heroin use both went up in the '90s and early 2000s, but the overdoses we're seeing are the problem that are killing people.

Adriana: As Ryan said, America is in the middle of an overdose crisis that's affecting American families and communities at large. But this crisis hasn't always been easy to identify. For parents or family members, it's often difficult to see the initial signs of substance use disorder.

Adriana: At the time she lost her son Cory, Cheryl Juaire didn't understand the magnitude of the overdose crisis that was at hand.

Cheryl Juaire: He was going in and out of detoxes, rehabs, and all that. And again, he was doing it with his brother, so I thought ... I mean, they would joke when they were going into a detox like, "How many girls are we going to pick up?", you know what I mean? So I thought it was a joke. And I would tell them, "Both of yous, knock it off. Fix whatever you got to fix when you go in there and come out."

CJ: So with the jail, he did some time in jail. And then he had a daughter and it was a really rocky relationship with this girl. And I said, while I was in Florida, I said, "You know what, Cory, just come on down and spend a week. Get a week's vacation." He had to jump through hoops to get the judge to sign off because he was on probation and he was living in halfway house. So the day before he was to come down, I called and called and called him all day long. Left messages. I wanted to make sure he had a ride to the airport. And I just knew that I knew that something was wrong. His oldest brother is a police officer, so he went and did a wellness check. He didn't do it, because it was in a different town. He called them and asked them to do a wellness check, and then he called me and told me that he had, Cory was dead. From an overdose. And that was the hardest call I've ever had in my life, especially from my son, another son.

CJ: So the day after, we flew back, because now I have to go bury my son, and we went to the apartment and there were needles all over the place. Did he die of ... He had been clean for a while, but I wasn't living up here, so I don't know. Some times I wonder, did he do it intentionally because he was really sad and messed up, that I've learned more since he's been gone. Or was it like his last hurrah because he was coming down to Florida and he couldn't take it on the airplane? I could beat myself up for the rest of my life, but I choose not to. My son is in heaven. He gives me signs all the time. And that's what happened there.

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season three: The United States of Opioids: Behind a uniquely American crisis

Adriana: Back in 2011, the most commonly used drug was cocaine. That has since changed dramatically. Sheryl had no idea that this was the beginning of what's become today's opioid crisis. Yet she knew that she didn't want Cory's death to become just another figure of data.

CJ: I cried a lot. I suffered in my grief a lot. I'm originally from Massachusetts, so we decided to move back home. My son was buried up here and I was flying up every three months, so it just made sense just to come home, we just wanted to come home. So we did that. And I joined a couple of groups on Facebook. And through that, one night, this mom reached out to me and she sent me a message and she says, "I know this is last minute, but tomorrow night there's six of us moms," know what that even meant, "going out to dinner and would love to have you come. And we're all from Massachusetts." So I said, "Okay. I'll show up."

CJ: So anyways, long story short, I showed up. There were seven of us and we pretty much closed that restaurant. We laughed, we cried, we shared stories. We shared things that I thought at one point I wanted to die because the pain from my grief was so bad from losing my child. I wasn't going to kill myself, I just didn't want to live anymore with that pain. And I found out they all felt the same way. So I was like, "Then I guess it's normal."

CJ: Well, one of the things that we discussed at that table was over time, people forget our child. They forget their date of birth and their date of death. And with us, it's something we're never going to forget ever. And only we knew that and only we felt that way. So when I created the group, it was just for us seven and I said, "Okay, so you need to give me your child's name, their date of birth and date of death, because in this group we'll never forget it and I'll always make sure we remember." Well, long story short, it started with just us seven and then just grew and grew and grew because of the epidemic and we now have a national organization and we have 16 state chapters. We have a chapter for siblings all from child loss.

Adriana; A big part of Sheryl's work is trying to eliminate the stigma that comes with having a friend or family member struggling with substance use disorder.

CJ: The whole concept behind team sharing is we're grief support. And there are so many people out there walking along like a zombie like I did that for me, my goal is to reach out and have a chapter in every state. But the stigma is still alive, like down south. There's a lot of people that are in complete denial. There's somebody we just recently found out who just lost their son in Massachusetts, and he won't come forward and tell anybody how he passed. They said he died from a heart attack, which he may have, but we know it was caused from his use of drugs.

CJ: So there's still the stigma, but there's the people that are just, they're going to have pain. When you lose a child, and it doesn't matter how you lose your child, when you lose a child, there's no greater pain in this world. And we all know that.

Adriana: Why do you think that there is this stigma still, particularly in the south towards losing somebody to substance use disorder?

CJ: Because I think people look down on you. Your child died from an overdose? He must've been a bad kid. You must've raised him wrong. You must've done something wrong. And that's the mentality of thinking unless it's touched them, really touched them, unless they know somebody, they're just going to be ignorant to it. Unless they come and say, "Tell me about that loss. What happened?" And when we can educate them, that's when it will change things. But the ones who have been in the throes of addiction, the ones who have lost their children to addiction, we all know and we all get it.

Adriana: You've been in recovery for 18 years. And in that span of time, what is it actually like being in recovery? What does it entail? You go to meetings frequently and you've also become, I think you said social worker essentially-

Andrew Burki: Yeah. I went to college for that.

Editor’s Note: After the time that this podcast was recorded, Andrew Burki was arrested on three counts of sexual assault, aggravated assault on a domestic violence victim, and possession of a firearm magazine capable of holding more bullets than allowed under New Jersey state law.

Adriana: Yeah. So what has it been like in those 18 years for you since?

AB: I mean, it's pretty great. But you just stabilize after a period. Like the beginning's so hard. The beginning's so difficult because you don't really have a frame of reference.

Adriana: Is there a lot of temptations?

AB: At the beginning. Because you don't ... and this is why it's so important that you have all these support services at the beginning. Now it's not at all. I'm just a normal run of the mill American that happens to not drink and not use. It's not even like ... It's a major part of my life and what I do and my identity, but it's not the entirety of my identity. There's so many other things that I am. I'm a social worker. I'm a husband to my wife. I'm a father to my son. I'm a son to my parents. I have an adult child to adult parent relationship. And our relationship has changed significantly. They used to pay money to fly me away from them. I now pay money to fly their grandchildren to them. It's really, it's improved significantly over the course of being in recovery.

AB: But I think the main thing that's so important is that we can and do recover. Given proper support, we can and do recover and this is a very common misconception, because it's in every single ... You know, the drama around people with substance use disorders is in the relapse, right? So you never have, like in pop culture, movies, TV shows, whatever, we always relapse. That's all they ever show. I mean, that's the stuff that drives me crazy. They never just are like, "Here's a storyline. Here's a person. They had a substance use disorder. They got it under control, they entered recovery and they're just living their life. Just doing regular," and that's what it is. Being in recovery is owning a house, paying taxes, dropping your kid off at preschool. It's vastly less dramatic. It's calm. There's a fair amount of vacationing and travel involved because you don't have to spend so much money on drugs.

Adriana: Andrew and Cheryl have different but personal experiences with substance use disorder. It's easy to have images in mind of who uses and who doesn't. But through our reporting of this story, we've learned that those assumptions aren't really true. We asked Ryan what he's noticed in his years working in the emergency room.

RM: The biggest thing here is that everyone probably has in their mind kind of the picture of who they think is overdosing, and that's kind of reinforced by what our society teaches us about people that use drugs and kind of like movies and TV. And the people who overdose and who use drugs in general are not some sort of bad element of society. They're not always just like vagrants and people who are choosing, making bad choices for lack of a better way to say it. It's really something that affects everyone. I've seen young kids, I've seen elderly people. I've seen people from the best families, people from the worst families. It is really something that affects everyone and I think that's kind of the most surprising thing. And what sticks with me is just the surprise from people, family or friends who just had no idea that their 65 year old grandmother had been using opioids, or their teenager had been using opioids until it's too late.

Adriana: Dr. Marino is a very vocal voice on Twitter, often debunking the many myths and misconceptions that come with opioids, particularly fentanyl. One common misconception is that fentanyl can be ingested simply by touching it.

RM: And so, we do know a lot about fentanyl. This isn't something new to us. And so people worry a lot that this is contaminating public places, you can touch it, it can go through your skin, it can get into the air. And we know from experience that that isn't the case. Fentanyl is very predictable and the only way to get toxic from it or to have an overdose is really by injecting, snorting, intentionally using drugs.

Adriana: I just want to clarify here because again, this is often falsely passed around that you can ingest fentanyl just by touching it and you cannot, correct?

RM: For all intents and purposes, no.

Adriana: Okay.

RM: Just casually touching fentanyl, even a large quantity of fentanyl someone bought off the street would not absorb through the skin in any significant fashion and would not cause an overdose. I think for the most part, these are people who just have bad information. They've heard that fentanyl is killing hundreds of thousands of Americans and they're at a scene where someone had probably a significant overdose, they see some powder, it gets on them. It's a very serious thing, especially if you're seeing someone who either died or is on the brink of death, you're hearing that fentanyl is killing all these people, you're hearing that it's super potent.

RM: There's a lot of social, kind of societal beliefs around fentanyl and I think those kind of contribute to probably more like a panic attack or something kind of similar to the placebo effect, which there is actually a negative placebo effect called the nocebo effect where if you believe something is going to be so detrimental to you, you can actually have symptoms as well. It's never been described that any of these people have ever tested positive for fentanyl or have had actual symptoms of an actual opioid overdose.

Adriana: What kind of consequences do these myths and misconceptions have as a result on people who are actually addicted to fentanyl?

RM: I think probably the two biggest consequences, first of all, these myths kind of snowball and give credence to themselves where this become kind of like a self fulfilling prophecy where if you've heard 100 stories of people just dropping down from being in the same room as fentanyl, then it's going to make you think if you're in the same room as fentanyl, you're going to drop down. But in terms of for people who use drugs, these are very harmful because people are very wary to go respond to an overdose. People will not want to touch someone who has overdosed. It really contributes to kind of the stigma that these people face and how they're treated very terribly, but even more importantly now, it's leading to people not getting resuscitated and people are probably dying. And I've seen even healthcare workers who have been too scared or not wanting to respond to an overdose in the appropriate way because of these myths.

Adriana: I tried to put myself in Ryan's shoes here for a minute. What's it like to have these people, countless patients coming in and needing to be saved from an overdose? What does a doctor say to them after such a dramatic event? We asked him what the right way to approach this is.

RM: Everyone responds to an overdose differently and I think one of the things that I've seen a lot throughout my career is just a lot of times people want to kind of use it as like a teaching moment, kind of tell someone, "Look, you almost died." And I do think that it is kind of a moment to try to talk to someone, but you have to go about it in a careful way, and telling someone that their family's mad at them or they made a big mistake is really not the way to communicate with someone who's in a very vulnerable position. It is a great opportunity to kind of try to engage someone, see if they want to get plugged in to recovery for, if it's opioids or whatever other drugs they're using. And I think a lot of times, this is not offered and that's kind of another way that the system I would say has dropped the ball on this issue is we have very good medicines and other options for getting people off of opioids and treating addiction, and these have been around for decades, and they're just not available.

RM: And probably the best example of this is Buprenorphine, which is a great medicine for treating opioid addiction like long term and has great success rates, has been well studied. There's a very large body of evidence supporting its use. It's a federally restricted medication and approximately only 5% of eligible prescribers, which is doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants across the country are actually able to prescribe this medication just because the federal government has restricted its use, because it's associated with addiction and drug use and we've kind of had a long history of bad laws that make treatments for those kind of people hard to access or just not available.

Adriana: You've talked a lot about stigmas here. What is the one that bothers you the most?

AB: The whole conversation around stigma bothers me the most about stigma, because stigma is ... We have a serious problem with stigma, but what we really have a problem with is we have a problem with ... We have an empathy gap. That's what we have. The fact that there's people that are like, "You should lock them up. Well, it's their choice. If they die, that's on them." That lack of empathy is the most detrimental component to our society.

Adriana: Andrew told us a story of someone who had a different background than his and the obstacles they overcame to get the care they needed.

AB: There's this kid, Reno Harmon out of Philadelphia. Experienced, I mean, just horrific trauma. He's like, you know, 12 years old. Watches his 11 year old best friend get shot through the throat, bleed out and die in front of him. On a basketball court. He is from this socioeconomically disadvantaged minority population. The whole deck is stacked against him. At 15 when I started getting into trouble, like my parents were coming in and cleaning it up. At 15 when he got in trouble, they put him in adult prison as a 15 year old. Adult prison. They offered him 20 years in prison as a 15 year old, and thank god his mom is amazing. She just like marched in there and was like, "20 years is not, that's not a plea deal for a 15 year old. What are you guys talking about?"

AB: He's from this very rough area, very rough background. Rampant gun violence all over who gets to sell drugs where to whom. But he gets diverted over to this recovery high school. Now he's in recovery. He came out and spoke at the Mobilize Recovery event in Nevada. Graduated high school early. College in a trade program. He went out and did this story for YouTube. And he's amazing. He's amazing. And his life has fundamentally changed simply because he had access to care.

Adriana: We've heard of the calls to decriminalize drugs, and then we've also heard people say these people should just be sent to prison, they're taking drugs, they know what they're doing. Where is the middle ground for helping people with addiction? Just based on your experiences? Are there any other approaches that you would say could potentially work?

AB: So this is the big problem. There's a big push on harm reduction right now, which is first of all, it's a very broad term. Technically, I'm obviously not a fan of it as a person in recovery and as a person who's formerly incarcerated, but jail is harm reduction from a societal standpoint. That's why people want us sent to jail. I don't think it's an effective solution. There is actually a lot of research to support the fact that it's not an effective solution. The bottom line is you should, anyone should want people to get help, even if they don't care about the people at all. Even if you're just a soulless monster and you don't care about your fellow Americans at all, you should still want them to get help, because if we go to jail and are not treated during the course of our experience there, at some point we're coming out. And I'm either going to come out with a treated or untreated substance use disorder.

AB: And then the other thing is it's just super expensive. I mean, you're spending like $75,000 per person per year to incarcerate and some states are astronomical. You guys just had, what, $330,000 per year to incarcerate an adult in New York. We could support someone for 20 years with a very expensive front end intensive treatment. And nobody needs 20 years of support. People need a five year long continuum of care. And that's what people do that have resources. You don't have all these celebrities coming out and being like, "Just celebrated 20 years" or 25 years in recovery, "It's the cornerstone of my entire career. My whole life is built on it. This is why I'm an A list musician," or whatever, "It's because I made this fundamental change in my life."

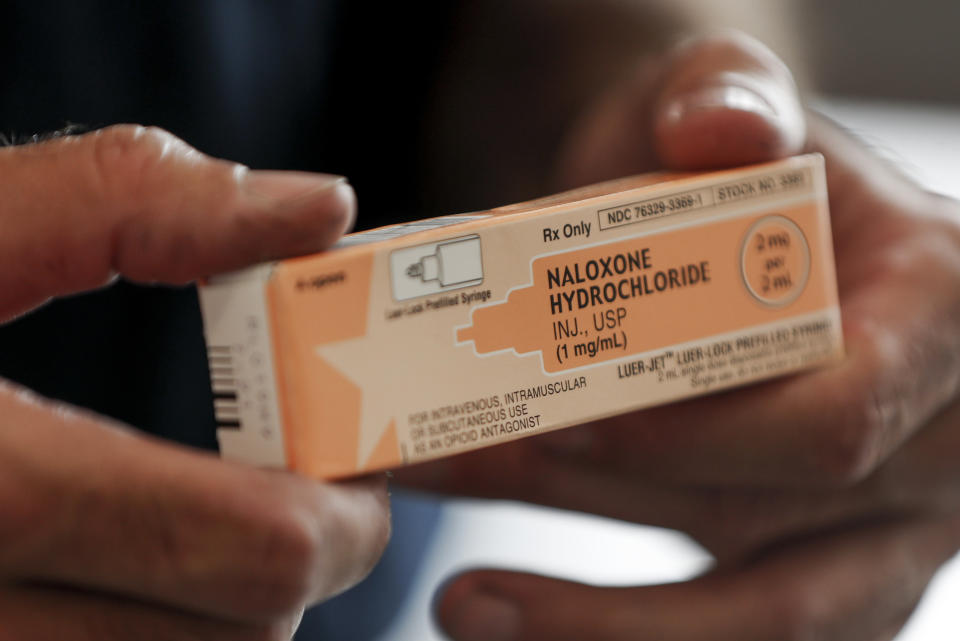

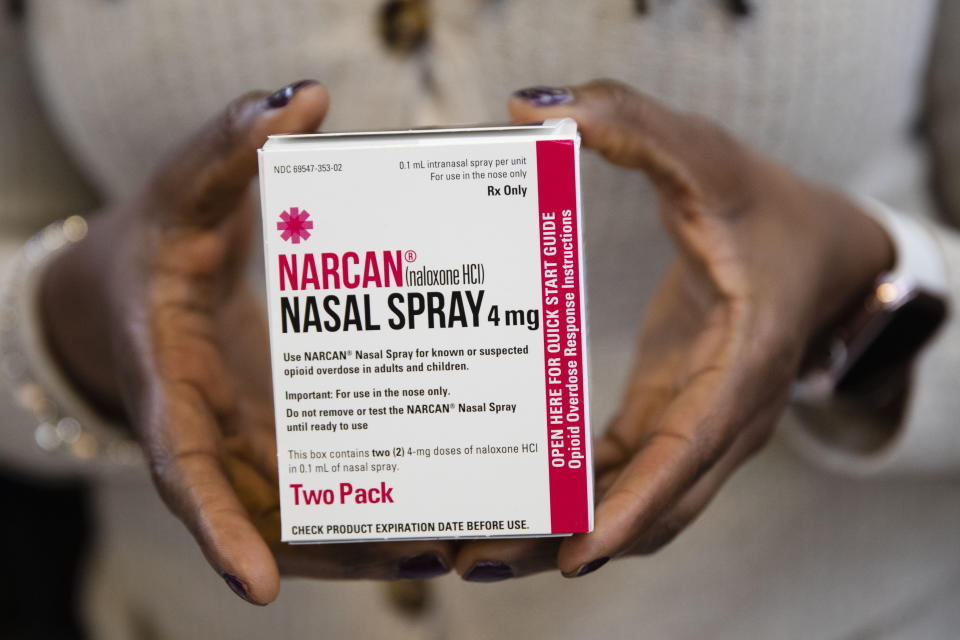

AB: And it's like I wonder if they have something that other people don't have. And it turns out that yes, they do, and it's a lot of money. That's what is making the difference. And it's the same for people like me, it's the same for people like my wife that had the deck stacked in their favor, that had access to all these systems. So when we talk about harm reduction in the US, harm reduction in the US needs a lot more funding. Safe injection sites is a big one right now. First of all, leaving aside the fact that safe injection sites should be operated out of hospitals by nurses and doctors, not like a bunch of volunteers in a warehouse with some donated NARCAN, just from a safety standpoint, it's about the wraparound services.

AB: So in other countries, in Canada and Switzerland, places like that, you go to somewhere that is providing this service and every single day they're like, "Do you need help? We'll get you help right now. I know you're just trying to get high, but let's talk about how wildly dysfunctional your life is right now and how we can help you." In the US, we're not providing any of those wraparound services and harm reduction without wraparound services is just hospice care for the poor. And that's really what we're talking about rolling out at scale here.

AB: And just think about it rationally for a second. If you're a homeless 16 year old girl who's addicted to heroin and you're prostituting yourself to support your substance use disorder because you're 16, you dropped out of high school, you don't have a lot of marketable skills. And you go to something like this, that's great. They're less likely to overdose. I mean, they're less likely to overdose if they're using fentanyl testing strips and things like that, but if they overdose, there's someone there that is going to provide reversal medication so that it's not a fatal overdose, so they're less likely to die. But you haven't addressed any of the underlying problems. They're still homeless. They're still prostituting themselves. You still have to commit crimes to get money to buy drugs. And this is why it's so important that if we're going to do harm reduction in this country, which I'm for, I support harm reduction, we need to pump a lot of resources in.

AB: Are we getting you access to housing? Are we getting you access to education? What are we doing to help you? Because that child should have the option of saying, "I need help," and we should get them into detox where they will immediately not be homeless and they will immediately not be prostituting themselves. Like that night, those issues are resolved.

Adriana: There's still a lot of work to be done. And if there's anything this story has shown is that there's no one clear cause or one clear solution to this American overdose crisis. At the end of the day, this crisis is about people. It's easy to begin thinking of these huge numbers and problems as insurmountable and difficult to solve. But every number lost was actually a person. I asked Cheryl where her family is at now, nine years after Cory's passing.

Adriana: So you said that your oldest son is a police officer and then what about your other son?

CJ: My other son, he used to do drugs with Cory and after Cory passed, he did them worse for a couple of years. I thought I was going to lose him. And then he got into recovery. He went to Teen Challenge. Stayed there a couple of years, and then they hired him and he worked there a couple of years and then he relapsed. So right now, that's where he's at. It's not good, but that's where he's at. A lot of families I have come to know have lost two children or have one that's in active addiction. We have a mom who lost five in our group in Massachusetts. Five children. It knows no boundaries.

Adriana: Illegal Tender is made by Yahoo Finance at our studios in New York City. This episode was written and hosted by me, Adriana Belmonte. Illegal Tender was created, edited, and produced by Alex Sugg. Thank you to Ben Westoff, Ryan Marino, Andrew Burki, and Cheryl Juaire for contributing to this story. Westoff's book, Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic is available now from Grove Atlantic. If you enjoyed this podcast, head over to Apple Podcasts and leave us a five star rating and review it for the show. Until next time, thank you for listening to Illegal Tender.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

Adriana is an editor and reporter at Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.