Op-Ed: What King would say to Black Lives Matter activists today

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In his ”I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of “the marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community,” and reminded the nation that Black people could “never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.”

Instead of seeing Black people as the enemies of democracy — contemporary critics of Black Lives Matter call the activists terrorists — King understood them as the friends of liberty. He particularly understood the need to renew the vision and energy of the movement by embracing Black youth.

King worked throughout his career with younger people, whether he was trading fierce but friendly barbs about Black power with Stokely Carmichael, applauding the courageous activism of John Lewis, or encouraging young gang members to lay down their guns in exchange for the more powerful weapon of love. King was in regular contact with members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and while they shared a broad vision of social justice, they clashed on methods and style.

King was reared in a leadership culture in the church full of patriarchy and hierarchy. While there was often consultation and conversation with members of the church community, decisions were usually made unilaterally by the male religious head.

The SNCC’s guiding spirit was an amazing female leader named Ella Baker. Baker’s philosophy was driven by the belief that movements produce leaders, not the other way around, and that didn’t necessarily comport too well with the Black church’s charismatic authoritarianism.

There were the usual tensions between younger and older leaders, some of a more serious nature — King often swooped down in a town after the local work had been done, often by SNCC, taking with him the cameras and glory for labor the younger folk had contributed to but rarely got credit for. Beyond these tensions, however, King and what were essentially the Black Lives Matter activists of their day forged progress together, with the aim of changing the world and making it safer and saner for Black people.

As we celebrate King’s legacy, we should remember that today’s young Black activists who challenge the status quo are humanitarian leaders deeply invested in Black freedom and justice and making America a truly democratic society.

They are patriots and heroes because they are willing to risk life and limb for the building up, not tearing down, of America. Their disappointment with the nation, their rage against its lethal limits and fatal failures, is but love turned inside out.

Unlike white supremacists and domestic insurrectionists, they are trying to make America reaffirm its principles, its beliefs, its ambitions and its fundamental commitment to democracy for all.

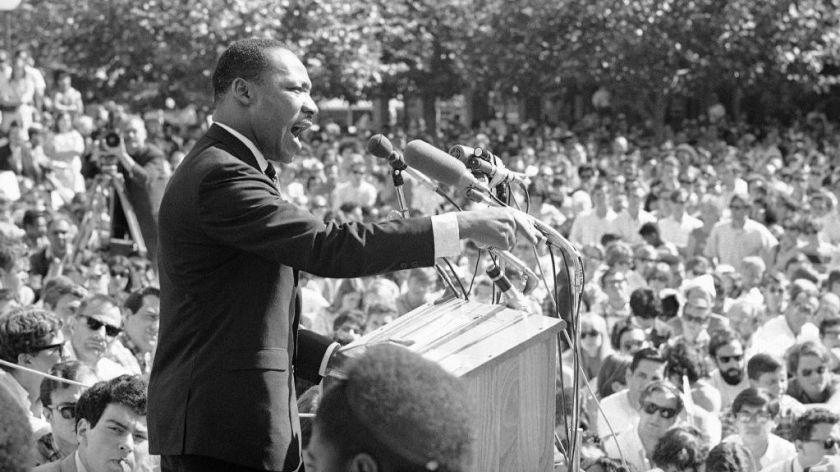

As King reminded America on that sunny day in August 1963, these principles cannot be realized if Black people do not continue to confront police misconduct and abuse. King understood then that the official power of the state to punish and murder Black people was fatal for a democracy. He also understood that too often law enforcement joined ranks with white supremacist forces to execute domestic terror that was protected by a badge and a gun.

In our day, the stakes of Black protest against racial injustice are heightened by the fact that more than a few members of law enforcement were directly involved in the recent Capitol insurrection. The tentacles of white supremacy stretch ominously into American policing. The ultimate paradox may be that many white followers of the 45th president rail against the very police forces that have historically had a hand in white supremacy’s deadly rampages against the Black people, who are its truest victims.

The bitter resistance of many white people to organizations like the FBI might be better understood coming from the mouths of Black people, even King himself, whom the agency deliberately chose not to warn when there were credible threats to his life.

Perhaps King’s greatest value to our present moment is to remind us that Black people have been willing to defend this country at every moment even when their lives didn’t matter to the people they protected. King’s nonviolent valor seems lost on white insurrectionists. It may be the height of irony that angry white people who benefitted most from American democracy are now willing to destroy it.

This article is adapted from a sermon delivered at the Washington National Cathedral on Sunday.

Michael Eric Dyson is a professor of African American Studies at Vanderbilt University and an author, most recently, of “Long Time Coming: Reckoning With Race in America.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.