'I get no respect': How Brian Jordan is the forgotten two-sport star

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Brian Jordan spent the prime of his life hunting hanging curveballs and unsuspecting wide receivers, barreling into second basemen like they were fullbacks and reading a quarterback’s eyes as if he were scrutinizing a pitcher fiddling with a grip in his glove.

Now, he writes children’s books.

Yet, even that pursuit crystallizes the drive, self-belief and fearlessness that enabled Jordan to stand unabashedly aside Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders as beacons of a fleeting and perhaps obsolete era of MLB and NFL crossover stars.

“I Told You I Can Play!”, Jordan’s literary debut, draws upon a childhood experience in which 8-year-old Brian is deemed too young to join a neighborhood football game with his brother and friends, all two or so years his senior.

An injury leaves the older boys no choice but to summon Brian onto the gridiron, whereupon he finds the end zone and his pride with equal rapidity.

“I held that ball up to my brother and said, ‘I told you I could play,’ ” Jordan remembers.

“I wanted to beat the older kids and show them up.”

Thursday, the NFL will commence its annual draft, a three-day pigskin bacchanal that will match 259 players with their new teams. There will be some All-Pros and Super Bowl heroes and perhaps Hall of Famers in the group.

But there will be nobody like Jackson, a Pro Bowler and All-Star Game MVP alike, perhaps the greatest athlete in modern U.S. sports history who, but for a hip injury, would have thoroughly married myth with reality.

There will be no one like Neon Deion, who played both sports with elan, once took a helicopter-private plane trek to compete for the Falcons and World Series-bound Braves on the same day and was talented enough to play both sides of the ball for the Dallas Cowboys.

And there will be no one like Jordan, who enjoyed a far better baseball career than Sanders and Jackson and played in almost as many NFL games as Jackson, yet accepts his spot in the pantheon of multi-sport greats.

“I tell people I’m the Rodney Dangerfield of two-sport athletes,” says Jordan, now 54, evoking the late comedian. “I get no respect.”

Yet examining Jordan’s body of work, 30 years after his tortured decision to walk away from the NFL and arguably the most charismatic team of that era, can tell us a lot about baseball and football.

It can tell us a lot about how we raise our athletes and how specialization robs them of a crucial hammer – leverage – that could be wielded on their behalf at every level.

And it tells us how control-hungry coaches may yet conspire to prevent another Bo, another Deion or even another Brian Jordan from blessing us with the full bounty of their gifts.

“I don’t think we’ll see another one,” Jordan soberly predicts.

Perhaps that’s because obstacles Jordan cleared have only grown higher.

Saying no

For the uninitiated: Brian Jordan could play.

Over 15 major league seasons – some of them part-time due to football obligations – Jordan hit 184 home runs, batted better than .300 three times, made an All-Star team, finished eighth in 1996 MVP voting and accumulated 33 Wins Above Replacement – putting him in a right field rent district that includes Shawn Green, Paul O’Neill and Nick Markakis.

In three NFL seasons, he was a Pro Bowl alternate, intercepted five passes his final two seasons and brought a physicality to the strong safety position that might look foreign in today’s more risk-conscious era.

That reality hatched from childhood dreams encouraged by his parents, who when Jordan was a first-grader urged him to write down his goals.

“That was my dream – to be different – to play two different professional sports," he says. "It came to fruition, through a lot of hard work and determination.”

And persistence.

Growing up in Baltimore as a three-sport star – yep, Jordan hooped in high school, too, but at 6 feet lacked the handle to consider a basketball career – he pursued his goals virtually unimpeded. As a running back and ballplayer at Milford Mill High School, Jordan had options – Cleveland drafted him in the 20th round of the baseball draft – but eyes for just one school: Maryland.

On a recruiting trip to College Park, a handful of upperclassmen sneaked him into a night club and Jordan sat at a booth, surrounded by offensive linemen and thought, “Oh God, I’m going to have a good career playing behind these guys.”

Yet when signing day arrived, coach Bobby Ross switched up: After previous assurances Jordan could play both sports in college, Ross asked that he skip baseball his freshman year.

It was a classic power play by a coach unwilling to share his athlete with another program. Jordan refused to capitulate.

“I looked at him and looked at my parents and said, ‘I can’t do that,’ ” Jordan recalls. “You’re talking about a major choice in a kid’s life. Me, I wanted to follow my dream and that was play two sports.

“The University of Richmond allowed me to do that.”

Richmond? The Division I-AA school seemed like a precipitous drop from the Atlantic Coast Conference. And Jordan arrived on campus with expectations he’d dominate.

When a senior-heavy roster of running backs relegated him to the sidelines, Jordan volunteered to switch to defense. The defensive coordinator was thrilled, the head coach unmoved.

Jordan would be redshirted, an indignation for an athlete with places to go.

“I went into the head coach’s office,” Jordan recalls, “and said, ‘Look, I’m not going to be here five years. I’m either going to be in the NFL or playing baseball.’ "

True enough. The Cardinals drafted Jordan with the 30th overall pick in 1988; Jordan signed with the Cardinals but stipulated he’d play his redshirt junior football season at Richmond.

Another year of laying the wood to Division I-AA opponents earned Jordan a Senior Bowl invite, and a chance to convert his pre-draft third-round grade to something better.

Mission nearly accomplished: Jordan left a strong impression in practices with the Dan Reeves-led Denver Broncos staff that coached his North squad, and might have played his way into the first round.

But during the game, while attempting to tackle Miami running back Cleveland Gary, Jordan got caught between the ballcarrier and a teammate, and suffered a dislocated ankle and broken fibula.

The Broncos drafted Hall of Famer Steve Atwater; Jordan underwent surgery under the watch of the mortified Cardinals, fell to the Buffalo Bills in the seventh round and astounded their doctors when he was able to run by minicamp, three months after his injury.

The Bills were just beginning a run of six consecutive division titles and soon, four straight Super Bowl losses. After a productive preseason, Jordan thought he’d made the team when, on cutdown day, there were no knocks on his door.

Yet he was eventually summoned from the training room to see coach Marv Levy, who had an offer, not a guarantee: Go on injured reserve for the entire year.

It was time to say no again, this time to a future Hall of Fame coach.

“My heart just sank,” says Jordan, who was not yet fully recovered from his injury, “and I looked at him and said, ‘After going through what I did, only to be on injured reserve …’”

The Falcons snapped him up on waivers before he could even get back home, a transaction with lifetime implications.

2 legit

Atlanta, shall we say, was not Buffalo.

Jordan parachuted from a veteran camp led by Bruce Smith and Cornelius Bennett to what would be three years of controlled chaos.

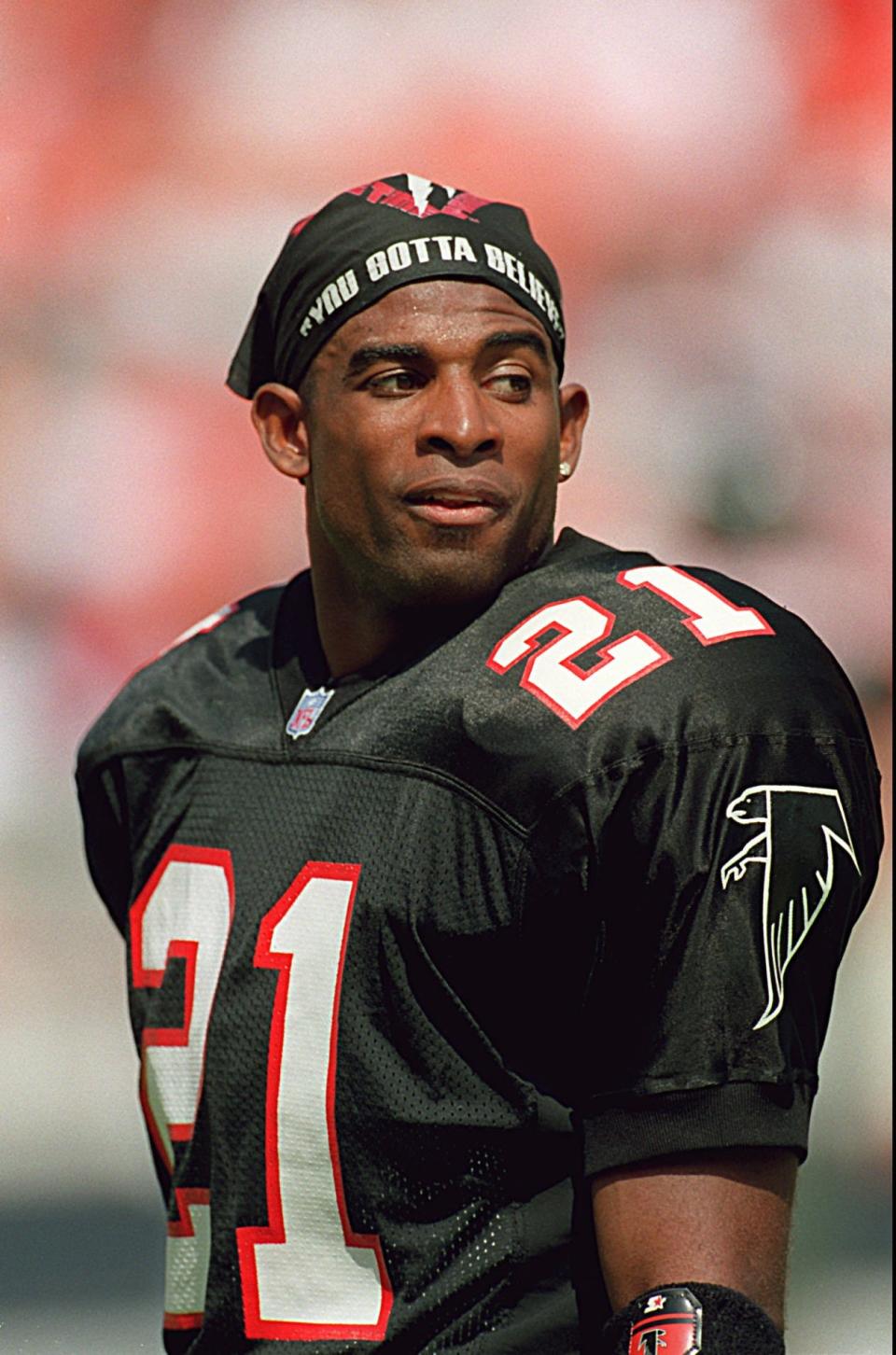

Sanders, drafted fifth overall in the ’89 draft, peppered practices with incessant trash talk, pitting defensive backs against receivers. Coach Jim Hanifan was fired after an 0-4 start. Jordan, finally mended, would be activated for the final four games of the ’89 season, setting the stage for two productive seasons and one unforgettable ride.

Coach Jerry Glanville’s arrival in 1990 brought a coach clad in black, matching the team’s new uniforms, and the squad would soon become an indelible slice of ‘90s pop culture.

Little was sacred, from Glanville mockingly calling Jordan "Baseball" in the film room, to the defense designating a “Homie of the Week,” a player who whiffed badly on a tackle in a game and thus would have to wear a practice jersey patterned after Damon Wayans’ “Homie The Clown” character on the nascent Fox network’s "In Living Color."

The Falcons went just 5-11 in Glanville’s first season, but four days after losing their 1991 opener, came an unexpected defining moment: MC Hammer’s release of 2 Legit 2 Quit, the title track of the Oakland rapper’s fourth album.

It soon became a Falcons anthem, a rallying cry for a team that would win eight of its last 11 and claim the first playoff berth since 1982.

In November, Hammer’s video for the song dropped, featuring a panoply of sports stars including Glanville, Sanders and Andre Rison, who welcomed Hammer to their sidelines. Heavyweight champ Evander Holyfield would join him. Fulton County Stadium was suddenly star central.

Sanders’ high-stepping after interceptions soon gave way to the Falcons aiming to reach the end zone after every pick – a lateral-fest that tossed risk aside in favor of fun. After closing a playoff game in that fashion, ABC analyst Dan Dierdorf called it one of the "stupidest plays I've seen in a long time," the swagger too astonishing for the VHS era.

“It was crazy, man,” says Jordan. “It became an Atlanta community football team. Everybody loved us. That’s the way we played the game. People thought we were reckless, but sometimes reckless works.

“I was the humble guy in the corner just admiring everything. I didn’t speak up too much when the celebrities came through.”

He just balled, developing a symbiotic relationship with Neon Deion: Sanders, Jordan said, promised to shut down half the field, and Jordan would make all of his tackles.

They won at New Orleans in a wild-card game before losing to eventual Super Bowl champion Washington. Soon, the sugar high of that season would wear off.

Jordan’s part-time minor league stints in the Cardinals system had gone well – he posted a .342 OBP at Class AAA in 1991 – and his rookie contract with the Falcons expired. As Jordan debuted in the majors in April 1992, he waited – and waited – for Glanville and personnel director Ken Herock to call.

Instead, the Cardinals pounced.

They offered him a guaranteed $2.4 million over three years – with a $1.7 million signing bonus – but the contract was ironclad: No football.

“I can’t tell you how tough it was, man,” says Jordan. “I was so mad at the Falcons for dragging their feet because I was not yet ready to hang up my football cleats. I was just learning how to be a really good football player.

“It was frustrating. To give up the game of football that I loved more than baseball at the time. But I knew my body was going to take a pounding.”

Turns out he bounced at the right time – the Falcons went 6-10 the next two seasons under Glanville, who along with Herock made a slightly more egregious move than freezing out Jordan that off-season – trading backup QB Brett Favre to Green Bay.

A ride like no other

Perhaps, had he devoted himself to one sport, Jordan would have been a superstar, Batman rather than everyone’s Robin.

Yet he had one heck of a view riding shotgun, from the Falcons to successful big league stints with the Cardinals, Braves, Dodgers and Rangers.

Jordan essentially had to learn how to hit at the big league level, with Ozzie Smith chastising him for “not learning anything” in the minor leagues. Yet he’d soon provide lineup protection for legends, from Chipper Jones in Atlanta – “He’d pick a pitch out and not miss and I’d be like, ‘How can you be so good?’” recalls Jordan – to the wildest home run chase in baseball history.

You want pressure? Try taking batting practice right behind Mark McGwire in 1998, when crowds jammed ballparks early to see Big Mac’s power display – and then having to hit behind him in the lineup a couple hours later.

“You had to perform,” said Jordan, who shared that role with Ray Lankford, “or he wouldn’t get a pitch to hit.”

Jordan hit 25 home runs, with a .902 OPS, as McGwire belted 70 in a run that he later admitted was enhanced by performance-enhancing drugs. While McGwire and Sammy Sosa’s home-run chase boosted baseball’s post-strike landscape, Jordan got word the record wouldn’t stand for long.

“I remember exactly when all this was over, Barry Bonds told me, ‘You know what, I’m gonna break that record next year.’ So you knew what he was going to do. He certainly broke the record.”

Bonds was off by a little bit, hitting 73 home runs in 2001, by which time Jordan was back in Atlanta with the Braves, an All-Star appearance under his belt and roots firmly laid down.

He’d finish his career a Brave in 2006 at 39, nearly two decades after embarking on his gambit. He contributes to the Braves’ broadcasts on Bally Sports and, in addition to his children’s books, works with local schools on childhood literacy efforts.

Jordan grossed more than $50 million in his major league career and in hindsight, realizes how solidarity comes far easier to ballplayers, who never lack for veteran union leadership, than their NFL brethren, whose average career was three years in his era.

“The camaraderie and family atmosphere as far as the MLB Players’ Association vs. the NFLPA, it was totally different,” says Jordan, who endured baseball's 1994-95 strike, when veterans did not cross the picket line and a salary cap was averted. “Football is more of a selfish sport whereas baseball, we’re going to stick together to the end. There’s going to be a selfish interest of players when that (NFL) window is so small.

“When guys don’t stick together, it definitely made it harder.”

Jordan’s interest was piqued when Kyler Murray, now the Arizona Cardinals’ quarterback, won the 2018 Heisman Trophy while under contract with the Oakland Athletics. Yet Jordan understands why Murray went one way, what with the guaranteed money the NFL affords quarterbacks, and the intense demands of the position making an offseason second-sport “hobby,” as Bo Jackson put it, less realistic.

Murray was spotted last month at a Phoenix Suns game wearing an A’s cap, fueling speculation he still has eyes for baseball. Jordan can relate: Two years after walking away from the Falcons, the Raiders offered him a two-year contract to return to football. The Cardinals responded by extending his contract through his arbitration years.

Leaving the door ajar was always good business for Jordan. He hopes the dual-sport opening isn’t closed for good.

“Those opportunities are not here anymore to a lot of these athletes,” he says. “A lot of coaches just want you to play one sport. Parents are putting all their eggs into one sport. That’s not the way to do it.

“When I talk to kids I say, keep your options open. When you’re older, you’ll figure out which one you really love.

“But throughout the time, give yourself a choice.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 2021 NFL draft: How Brian Jordan is the forgotten two-sport star