Neighbors wanted to keep open space. The airport wanted industry. What happened?

Neighbors in the area have been resisting since the winter. Now, they’ve got most of what they wanted. But some are still uneasy about what the future of open space in South Boise looks like.

For months, Ada County residents along the city’s south border have been concerned that the Boise Airport’s plans to develop land it owns would mean the end of a wide expanse of sagebrush that abuts their neighborhood.

City officials heard their concerns and changed their proposal, so that much of that land will stay open space. For now.

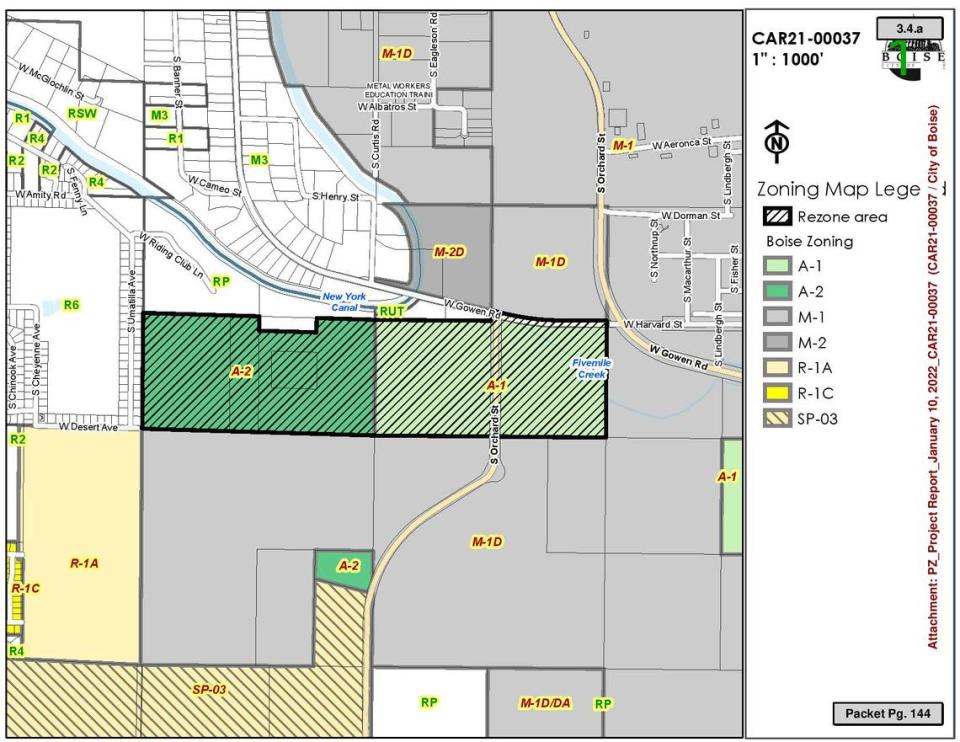

The city-run Boise Airport owns 153 acres east of South Umatilla Avenue southwest of the airport. Originally, the airport requested rezoning its entirety for industrial use. But the land is split between two zoning designations.

The eastern 75.5 acres are zoned A-1, meaning open space as a holding zone until development happens. The western 77.5 acres, closest to the neighbors’ houses, are zoned A-2, which is “intended for permanent open space,” according to Boise’s zoning code. That’s the portion neighbors objected to.

On Tuesday night, the neighbors got their way. The Boise City Council voted unanimously to approve a partial rezone of the area in question, allowing industrial development on the eastern portion, closest to the airport, and keeping the western portion as open space.

“We have to do this kind of stuff somewhere,” said Council Member Patrick Bageant. “The alternative is more sprawl into the desert.”

Boise’s last sagebrush steppe?

Neighbors who attended Tuesday’s meeting said they appreciated that the city had heard their concerns but still were unsure of what potential projects could be built in the rezoned area.

“I would feel better if I knew what kind of industrial development we’re putting in there,” one neighbor said. Other neighbors raised concerns about potential health impacts from future industrial use. The closest homes are about a half mile from where the industrial uses will be, according to the city.

Though the western segment of land that neighbors were most concerned about was left alone Tuesday, several neighbors still directed their comments at what advocates for the area say may be the last sagebrush steppe left in the city.

Estee Lafrenz, the president of the South Cole Neighborhood Association, said the area may be home to slickspot peppergrass, which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Lafrenz said her neighborhood wanted a development agreement, which would limit the scope of future development in the area, for the parcels that would become light industrial.

“Please city of Boise, protect our land,” Lafrenz said.

Shiva Rajbhandari, a student at Boise High running for the school district’s board of trustees, spoke at Tuesday’s public hearing, calling the sagebrush steppe ecosystems a “carbon sink.”

In response, Boise Airport Director Rebecca Hupp said “there is not endangered species on this parcel,” while also noting that the eastern portions of land had previously been farmed. She added that having airport development close to the airport itself would help the city meet its sustainability goals.

Neighbor formed Boise Open Space Alliance

Gregg Russell, who lives on South Umatilla Avenue with a vast backyard view of the Foothills, formed the Boise Open Space Alliance. The nonprofit distributed blue signs to neighbors that said “SAVE BOISE OPEN SPACE FROM DEVELOPMENT.” Russell organized his neighbors to fight and protect the land they consider precious.

Their top argument was that “permanent open space” shouldn’t be considered for a rezoning. Many neighbors, who live just barely outside city limits, have said they moved there specifically for the open space and natural beauty.

Members of the Western Riding Club ride horses in the area. Some neighbors think the southern parts of Boise should have more parks and land to roam without buildings around. Others have been worried about traffic, noise, pollution, safety and declining property values if industrial buildings are built.

The snag is that Boise’s land use map, which guides future development, designates all 153 acres for industrial use.

Though the airport did not give particulars for what kinds of development could occur on the eastern parcels, Hupp said that “we do not envision a trucking operation” that would require refueling onsite. The area would likely have warehouses or light manufacturing, she said.

The city picked Boise’s Adler Industrial as its preferred developer of the land if it was rezoned. In response to the city’s request for information, Adler projected it could draw $3.3 million annually in property tax revenue. Adler also touted that the city could benefit from economic growth, job creation and revenue streams that would help pay for the airport’s expansion.

City officials have said zoning can change any time and land isn’t protected unless easements, deed restrictions or other more legally binding agreements are involved.

The four “permanent open space” parcels were annexed into Boise in 2005. They took on the zoning that was most similar to their zoning when they were part of unincorporated Ada County. It stuck for 17 years.

What will happen to the land being left alone?

Some neighbors are still concerned for the long term.

The city is working on rewriting its zoning code for the first time since 1966. That means any property could be assigned a new zoning designation. Neighbors fear all the work put into this fight might be wiped away if the new zoning allows for future development.

The 77.5 “permanent open space” acres would be zoned as O-2, which is “intended for larger land areas for municipal development such as parks, schools, operations and other public, institutional, civic, and community uses,” according to a draft of the city’s new code. Land to the east and south is projected for industrial use.

The city’s proposed zoning code also has an O-3 designation, which is for “very limited residential development” and is also designed to “protect sensitive environmental resources,” according to a draft of the zoning ordinance.

On Tuesday, Lafrenz noted that parcels of park space in Boise’s Foothills are, in the zoning draft, expected to become O-3, whereas the land west of the airport is marked as O-2.

“Future development could destroy natural habitat lands for endangered species and risk habitat for other native plants and animals,” Lafrenz said.