There are nearly 9,000 craft breweries in the US – but big beer dominates

Like most of the country’s nearly 9,000 breweries, the Wichita Brewing company would like more Americans to drink its beer. That’s been an unexpectedly difficult hurdle for the Kansas company.

While craft beer drinkers in Kansas, Oklahoma, Missouri and Wyoming can enjoy Wichita beer, the brewery has been trying for a year to sell its beverages in Minneapolis. Its inability to do so is thanks to post-Prohibition state laws that force most breweries to rely on a limited number of distributors to get their products into stores, bars and restaurants.

Most of those distributors are tied to brewing giants Anheuser-Busch InBev or Molson Coors and take on only a handful of small, independent breweries, so craft brewers are forced to pitch their brands to the few wholesalers willing to consider them.

It’s a similar story for small breweries trying to grow in other parts of the US. The bottleneck, which has been exacerbated by the acceleration of new alcohol laws since 2012, means many small brewers can sell their beer only in their own brewpubs, since most states prevent brewers from distributing beyond their neighborhood – if they’re allowed to distribute it at all.

“Say you’re a small brewery and you want to sell beers to bars within a few blocks,” said Jeremy Horn, co-owner of Wichita Brewing company and president of the Kansas Craft Brewers Guild. “You can self-distribute up to a certain amount, but the wholesalers will fight hard even with that to prevent even one toe from getting over the line. It’s 100% self-preservation.”

While Anheuser-Busch, Molson Coors, Constellation and other mega-companies have snapped up scores of craft breweries over the past decade, acquisitions have slowed since Constellation’s disastrous $1bn purchase – and subsequent sale for a fraction of that price – of craft brewery darling Ballast Point.

But now, consolidation within the distribution industry arguably is having an even greater effect on beer drinking in the United States. The country has far more breweries than ever before – 8,800, up from about 1,800 in 2010, a stunning fivefold increase in just over a decade – but most craft beer is limited to the region where it’s brewed.

Just four firms dominate 78.6% of the market for beer sold in grocery stores in the US, according to an investigation by the Guardian and Food and Water Watch published in July, based on an analysis of sales data: Anheuser Busch (41.6%), Molson Coors (24.3%), Constellation Brands (8.9%) and Heineken NV (3.8%).

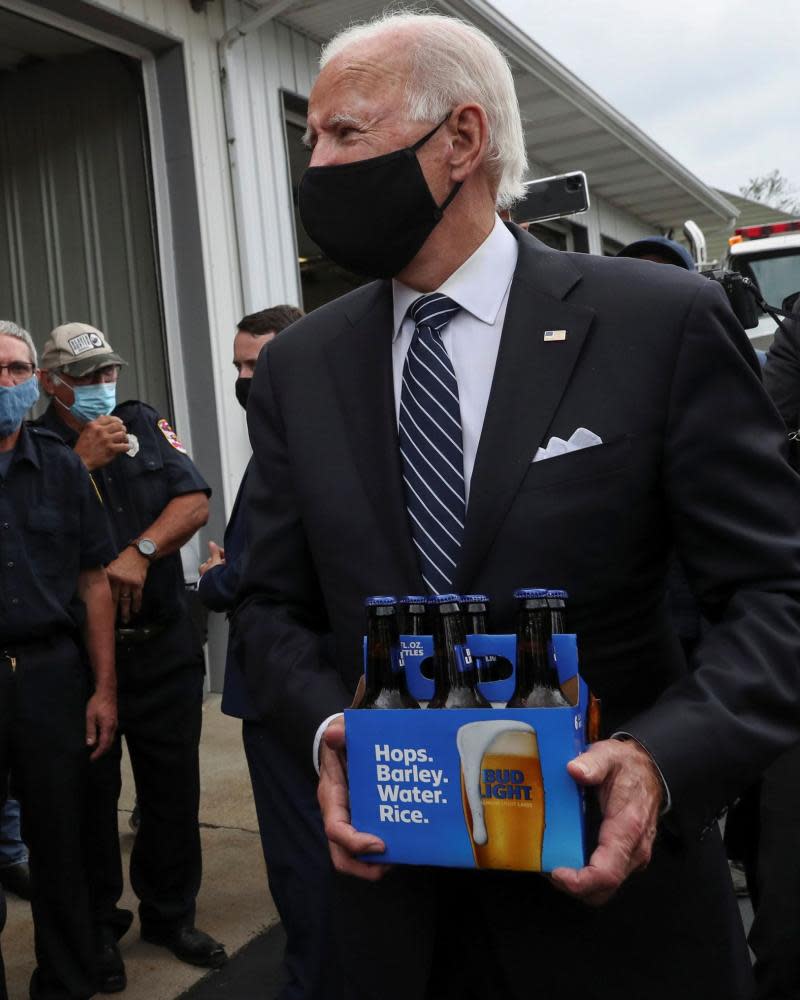

Earlier this year Joe Biden in July ordered a review of beverage distribution, including beer, “to protect the vibrancy of the American markets for beer, wine, and spirits, and to improve market access for smaller, independent and new operations”.

“It’s challenging for a lot of small brewers to get access to market when there’s this choke point, when your only option is to go with a distributor that already has 2,000 brands,” said Bart Watson, chief economist for the Brewers Association. “It makes it difficult for small breweries to grow. When you control the taps, you can control your own destiny. But it’s difficult to scale up.”

Even when a craft brewer can find a distributor, that doesn’t necessarily solve distribution problems, said Wyndee Forrest, president of the Nevada Craft Brewers Association and owner of CraftHaus Brewery in Las Vegas. “A distributor will go and collect brands just to prevent a competitor from getting it, but there’s nothing saying they need to distribute your brand,” she said. “I absolutely do prefer having a distributor, but if a brewery is just starting out and being forced to use a distributor that doesn’t represent them, that’s not a level playing field.”

In California, distribution is dominated by Reyes, the country’s largest beer distributor and a Molson Coors partner. Reyes does business in California as Harbor Distributing and did not respond to interview requests.

After Molson and Coors merged about 15 years ago, the company cut ties with several California wholesalers, including Mussetter distributing near Sacramento. Mussetter and some of the other companies spent a couple of years fighting the decision in court but eventually gave up because of the cost, said general manager Jason Mussetter.

It’s extremely difficult at this point to start the next New Belgium or Sierra Nevada

Trey Malone, professor

Mussetter started over from scratch in 2009 as a craft beer distributor and now carries about 55 brands. “We didn’t have anything to lose at that point,” Mussetter said. “We needed a portfolio.”

But even smaller distributors like Mussetter can’t handle the exponential growth in the brewing industry. “Long gone are the days when you could just walk up to a distributor and say, ‘Hey, I have a beer I’d like you to sell,’” he said. “You have almost 9,000 breweries now across the United States. There’s a limited amount of shelf space, a limited number of draft handles.”

Between the competition, consolidation and distribution challenges, don’t expect to find some of your favorite beers outside the brewpub down the street. The craft beer industry has split into two main branches: brands such as Goose Island (AB InBev) and Lagunitas (Heineken) that are owned by big companies and tiny brewers that don’t even distribute to the next town over.

While small breweries sometimes find success partnering with nearby bars, stores and restaurants, the competition for broader distribution is fiercer than it’s ever been. Retail opportunities haven’t changed much in the past few decades, said Paul Pisano, general counsel and senior vice-president for industry affairs with the National Beer Wholesalers Association.

“The 60 ft of the beer aisle at the Safeway today was 60 ft five years ago and 60 ft five years before that,” he said.

The explosion in American breweries “hides the fact that beer consumption is declining”, said Trey Malone, an assistant professor in the Michigan State University agricultural, food and resource economics department. “I think craft beer over time will become more synonymous with hyperlocalism. Most of those small breweries are basically bars that make their own beer. It’s like we’re going back to the 1800s.”

Few of those hyperlocal brewers should expect to grow much, Malone added. “It’s extremely difficult at this point to start the next New Belgium or Sierra Nevada.”

Sierra Nevada remains an outlier in the industry. The California-based brewery sold its first beer in 1980 and has remained family-owned as most of its competitors have disappeared or been bought by conglomerates. It partners with about 400 distributors nationally and has a second brewery in North Carolina.

Will there be another Sierra Nevada? That’s going to be tough in a country with almost 9,000 beer brands, said Joe Whitney, the brewery’s chief commercial officer. “We’ve been national for 16 or 17 years, a good long time,” he said. “It wasn’t easy by any means, but it’s harder now. There are times when I have trouble finding our beer on the shelves, and I can see it in my sleep.”

Most craft breweries produce fewer than 1,000 barrels each year, according to the Brewers Association, a craft brewery industry group. Some have been more successful navigating the tricky industry: Wichita Brewing produced 5,000 barrels last year, Horn said.

Tiny breweries, many of them owned by Bipoc brewers, have set up in almost every town in the country. Azadi Brewing company in Chicago produces fewer than 200 barrels a year, while Connecticut-based Other Desi Beer company produces 120 barrels and California’s Los Brewjos produces about 300.

Related: The illusion of choice: five stats that expose America’s food monopoly crisis

Both Azadi and Other Desi brew beers infused with Indian spices. Los Brewjos, founded by a group of Latino brewers, focuses on Latin American flavors. Beer drinkers are lucky to have thousands of innovative options, said Azadi co-founder and CEO Bhavik Modi.

“We live in an era when there are infinite niches,” he said. “Having a lot of breweries experimenting with those niches is really impactful.”

At Los Brewjos’ Los Angeles-area taproom, the Latin American flavors are paired with cumbia and rock en español, said Agustin Ruelas, the president and co-founder.

“We play a lot of music we listened to growing up, and a lot of people feel comfortable with that because they grew up with it too,” he said. “We don’t hide the fact that we’re Latino and we want to represent our culture in some way.”

Culture also is paving the path for another Los Angeles-area craft brewery, Crowns & Hops, one of only a few dozen Black-owned breweries across the nation. Owners Teo Hunter and Beny Ashburn plan to open a taproom in Inglewood next year, and their beer can already be found at Inglewood’s new SoFi stadium and such stores as Whole Foods.

The company is crowdfunding ownership shares and has raised more than $470,000. People of color deserve good beer and rarely see it, Hunter said during a break from shopping for bathroom tiles for the new taproom.

“As Black and brown communities, big beer companies have always targeted us with the worst products,” he said. “You’d never see a king or a queen with a crown with a 40-ounce. They’d want the best from their community.”