Mike Davis, 'City of Quartz' author who chronicled the forces that shaped L.A., dies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When it was first published in 1990, Mike Davis' "City of Quartz" hardly seemed a candidate for bestseller status.

There was its author, for starters. Davis was a Marxist urban scholar whose primary contribution to the public discourse at the time consisted of a little-read book about the history of labor in the U.S., along with dispatches on related subjects in the LA Weekly and the New Left Review.

There was also the book itself. Released by the lefty publishing house Verso, it was 462 dense, unsparing pages about the ways in which powerful interests in Los Angeles — namely, real estate developers, aided and abetted by politicians and the Police Department — had ruthlessly molded the landscape of the city to their whim, principally at the expense of the working class and people of color, all while promoting myths about backyard living.

"City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles" was almost irrationally ambitious. The book contained a kitchen sink's worth of subject matter covering the design of corporate superblocks, cul-de-sac NIMBY-ism and the ongoing faceoff between the cultures of boosterism and noir, buttressed by copious footnotes and references to Marxist theorists such as Antonio Gramsci and Herbert Marcuse. And its cover? A looming image of the Metropolitan Detention Center in downtown Los Angeles by photographer Robert Morrow.

Yet "City of Quartz" quickly materialized on bestseller lists when it debuted. As reporter Susan Moffat wrote in The Times in 1994, Davis' work "managed to turn local zoning battles into revolutionary high drama."

It also turned Davis into a public intellectual. His visions of the city's "spatial apartheid," as described in "City of Quartz," had initially been chided as apocalyptic by some critics. But the 1992 uprisings, which left swaths of L.A. in cinders, showed that his analysis had been prescient.

Decades later, in a 2020 podcast interview with Los Angeles critic and scholar David Kipen, Davis still seemed a bit baffled by his work's success. "I was utterly shocked that anybody bothered to read this book," he said.

"City of Quartz" wasn't just read, however. It was devoured.

"When you judge the work of somebody, it’s what the work itself did, the ways it makes us think differently," said historian William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. "Equally important: How many ships did it launch? And 'City of Quartz' launched so many ships — whether it’s dissertations or conferences or articles."

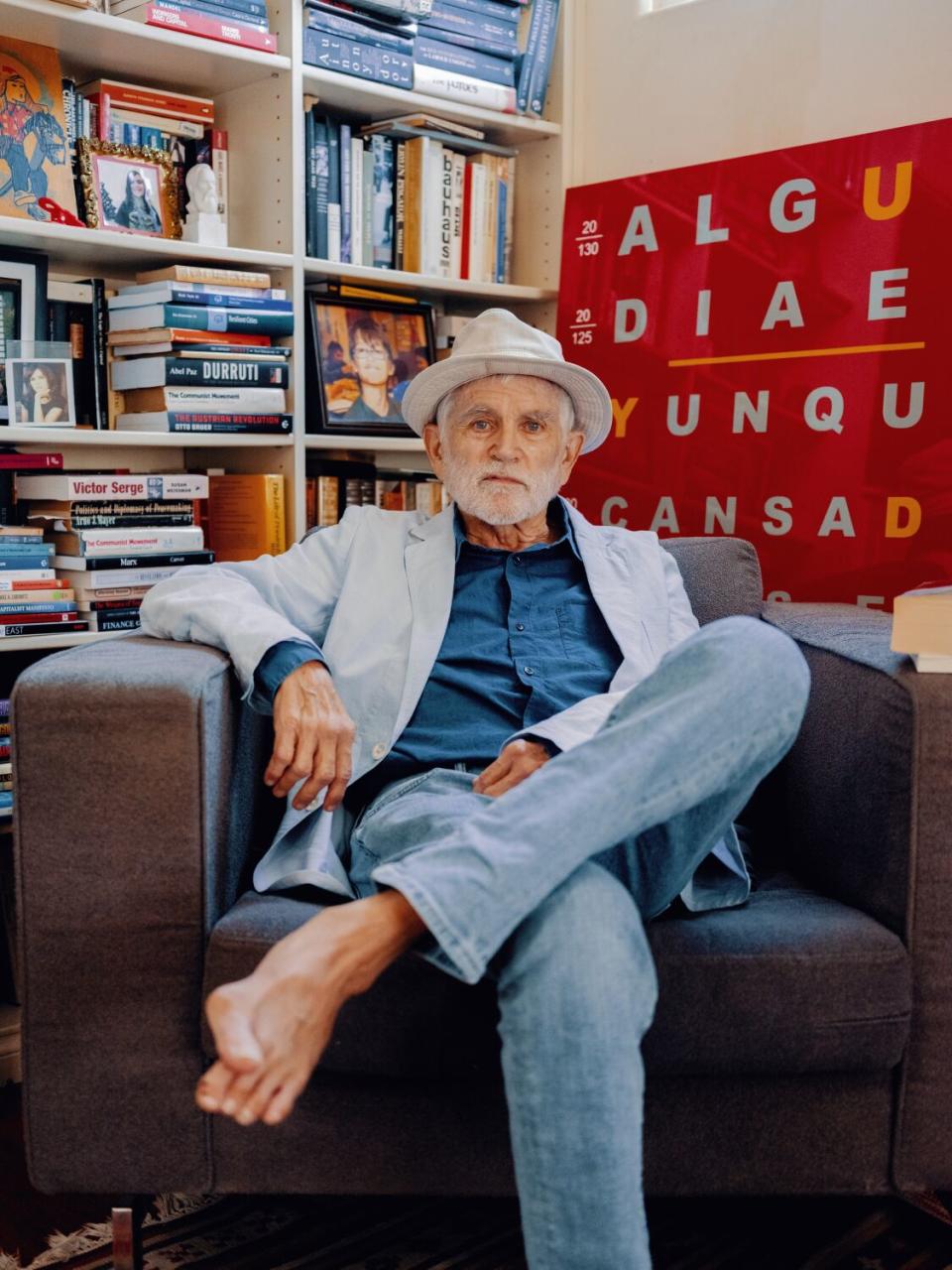

Davis, a writer whose work exposed L.A.'s social fractures and disquieted its most ardent boosters, and whose mark on the intellectual history of Southern California remains indelible, died Tuesday at his home in San Diego from complications related to esophageal cancer, according to his daughter and literary agent Róisín Davis. He was 76.

In an interview with Times reporter Sam Dean in July, he accepted his terminal diagnosis but said he had hoped for a more dramatic ending. "If I have a regret," he said, "it’s not dying in battle or at a barricade as I’ve always romantically imagined — you know, fighting."

Davis is survived by his fifth wife, artist, curator and scholar Alessandra Moctezuma, their twin children, James and Cassandra Davis, as well as two children from Davis' previous marriages: Jack and Róisín Davis.

Though best known for "City of Quartz," Davis wrote more than a dozen notable books over his more than four-decade career, including 2020's "Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties," which he co-wrote with historian and journalist Jon Wiener. In true Davis style, it's a thorough work — 800 pages — and a profound examination of ’60s activism in a city that had often been written off as apathetic during that era. Critic Jeff Weiss, who edits TheLAnd, described it as "a love letter" to "the idea of collective struggle."

More polemical was "Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster," released in 1998, about how the city's urban design was exacerbating fire and drought. It also, quite famously — or, rather, infamously — featured a chapter titled "The Case for Letting Malibu Burn," arguing against deploying vast public resources to save an area where "nouveaux riches" had built "with scant regard for the inevitable fiery consequence."

D.J. Waldie, the mild-mannered essayist behind "Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir," wrote in his review of "Ecology of Fear" that the book presented "a vision so dismal that it's ultimately paralyzing." Jill Stewart, a columnist for New Times Los Angeles, described the author as a "city-hating socialist."

And there was Brady Westwater (real name: Ross Ernest Shockley), a Malibu real estate agent and amateur historian who took it upon himself to fact-check Davis' work and send his voluminous findings to just about any journalist within reach of a fax machine. Some of the mistakes chronicled by Westwater and others were minutiae, but they also turned up bent truths: L.A. media and meteorologists were not, as Davis claimed, conspiratorially playing down the occasional tornadic storms that touched down in the city.

The Times followed up with a 5,600-word front-page story, in which reporter Ted Rohrlich fact-checked several dozen claims in Davis' books. His view: "Most of his stretchers appear to be the result of haste, wishful thinking and a taste for entertaining hyperbole rather than malice."

In response to that epic piece, Wiener wrote a letter critical of The Times. "If you put the same resources into checking footnotes in other books, you would find similar 'minor' errors," he wrote. "So how come The Times focused on social critic Davis, instead of, say, on a voice of the establishment like Henry Kissinger?"

The brouhaha ultimately did little to shake Davis' intellectual standing, nor did it undermine some of the bigger points he was making about the ways power and policy shape cities.

"That is the point with Davis: more theoretician than historian, more instinct than research," wrote the late journalist and L.A. River activist Lewis MacAdams. "The point is less what he discovers than which parts of the record he chooses to look at. Everybody knows that Malibu burns; it was not until Davis that anyone said, 'Let it.' Those who argue with his facts must still grapple with his argument."

If "City of Quartz" was an unlikely bestseller, then Davis was an unlikely intellectual star.

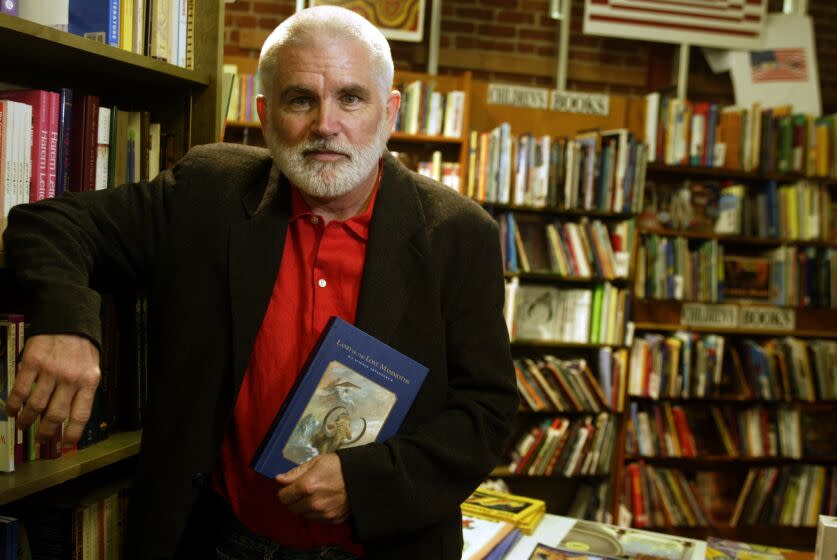

He began his career not in academia but as a truck driver for his uncle's wholesale meat company outside San Diego. The image of working-class tough was one he deployed to great effect. His author photo for "City of Quartz" shows him scowling under a flattop, arms folded protectively across his chest, a piece of brutalist urban infrastructure as backdrop.

This, along with his dour view of cities, led to some funereal descriptions of Davis in the press, where he was dubbed L.A.'s "dark prophet" and the "poet laureate of pessimism." The French daily Le Monde once baptized him a "prophète de malheur" — prophet of misfortune.

But if his public persona seemed foreboding, his personality wasn't. A generous scholar and mentor, Davis was at home in all worlds, conferring with feminist theorist Susan Faludi one minute and a former Crip leader the next. In the ’90s, he held regular gatherings at his Angelino Heights home where community activists like the late Levi Kingston would cross-pollinate with emerging young essayists such as Lynell George and Rubén Martínez.

He was instrumental in supporting young writers, especially young Black and Latino ones. He encouraged George to publish "No Crystal Stair: African-Americans in the City of Angels," her collection of observations about Black L.A. in the aftermath of the ’92 uprisings.

"When he said, 'You should do this book,' I felt I wasn't ready," George said. "He said, 'No, you're ready.'" He then helped set her up with a book contract.

George said Davis' most important legacy, however, remains the paradigm shifts he helped put into motion.

"He shifted the conversation," she said. "We were finally talking about L.A. not in relation to New York, but Los Angeles as Los Angeles."

Michael Ryan Davis was born on March 10, 1946, in Fontana, one of three children of working-class parents from Ohio (his father was a meat cutter) who hitchhiked to California during the Great Depression. When Davis was a young boy, his family relocated to Bostonia, a tiny hamlet in San Diego County on the outskirts of El Cajon.

As a teenager he held conservative views: "Right-wing, ultra-patriotic," he once told a newspaper reporter. And that was when he was actually thinking about politics. As a youth, he said, he was more preoccupied with "stealing cars a bit, trying to drag race and getting into trouble." He was, he told The Times in 1994, "pretty much your average redneck 16-year-old."

But a series of formative events would change his worldview — and, ultimately, the course of his life.

In high school, Davis became intrigued by "Hiroshima," journalist John Hersey's account of the atomic bombing of the Japanese port city during World War II. During this same period, a cousin who was married to a Black civil rights activist took him to a demonstration in downtown San Diego. There, as Davis later recalled in a 1997 interview with the magazine Lingua Franca, "A group of redneck sailors drenches us with lighter fluid, and one of the guys started flicking his lighter."

There were also the shifting circumstances of his family life. When Davis was 16, his father suffered a "catastrophic heart attack," an event that rattled the family financially. Out of necessity, he took a semester off from school to drive a delivery truck. The gig provided a needed paycheck. It also introduced him to the politics of labor and Marxism.

Over the next two decades, Davis lived an intensely peripatetic life, intertwining periods of work and study with travel and activism.

He attended Reed College in Oregon briefly, lasting only a couple of weeks before getting thrown out for living in his girlfriend's dorm. That stint, however, connected him with the left-leaning Students for a Democratic Society, and he became the group's first regional organizer in Southern California. The experience was essential to cultivating his activist streak. Later in life, however, he expressed disappointment with the student movement. "The New Left weren't heroes," he said. "We lost. The civil rights guys were the real heroes."

By the end of the ’60s, Davis had not only joined the Southern California Communist Party, he was running its Los Angeles bookstore. (His FBI file, by one estimate, exceeded 100 pages.)

Mostly, he made ends meet as a big-rig driver, delivering Barbies for an L.A. wholesaler. For a time he also drove a Gray Line bus, hauling tourists to picturesque L.A. sites such as the Fairfax Farmers Market, all the while sneaking in details about grim historical events such as the Chinese massacre of 1871.

By the mid-’70s, Davis was back in school, studying history and economics at UCLA courtesy of a scholarship from a butchers union. After receiving his bachelor's degree, he began coursework for a doctorate but never earned it. Instead, he relocated to Scotland, Ireland, then London, where for half a dozen years in the ’80s he served as editor of the New Left Review.

He returned to Los Angeles in 1987 — to a city, as he told Moffat, that "had changed beyond recognition." He resumed truck driving but a lack of unionized jobs meant worse hours and lower wages. "I felt like a sharecropper on the interstate," he later said.

He took a variety of teaching jobs at local colleges — though, without a doctorate, his options were limited. And he began to work in earnest on the manuscript for "City of Quartz," which brought together ideas he had been cogitating on for years.

The book catapulted Davis into the stratosphere. He was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award the year it was published. Other honors and academic residencies followed. In 1998, he received a MacArthur fellowship, the so-called genius grant.

"City of Quartz" is regularly cited as one of a cluster of highly influential books on Los Angeles and its environs. Since its initial publication, the book has been released in three English-language editions and translated into seven other languages.

In his review in the New York Times, the late USC journalism professor Bryce Nelson compared the "City of Quartz" author to "Nathanael West at his most somber." Davis, he added, "offers a dark, almost unrelievedly oppressive picture of life in a tough, hardhearted city."

Martínez, a journalist and a professor of literature at Loyola Marymount University, who has written on Davis' personal and professional legacies, first met the author when they were both at LA Weekly in the late 1980s. He said those who see only darkness in Davis aren't reading very deeply. "There is humor all over his work," he said. "It's a dark humor, but it's humor."

Indeed, to comb "City of Quartz" is to continuously stumble into Davis' barbs. Early civic booster Charles Lummis was "a malarial journalist" from Ohio. Yuppies are placed into an invented scientific taxonomy called "homo reaganus." The architecture of Bunker Hill is dismissed as "a Miesian skyscape raised to dementia."

"I’m not a writer’s writer at all," he told The Times' Dean, "but I am a damn good storyteller."

Throughout his career, Davis used darkness and humor (and critical theory) to paint a complex picture of Los Angeles. "It's not all apocalyptic," Martínez said. "It might be a cautionary tale, but it's at the service of a hopeful project."

As Davis once told a writer for Salon: "I love Los Angeles. How can you not see that? I suppose the book is, in the end, a failure if it betrays none of the sense of deep feeling I have about the city. But that's where being a radical comes in — you have to rain on the parade."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.