Mental Health: After personal struggles, criminology professor advocates for decriminalizing mental illness

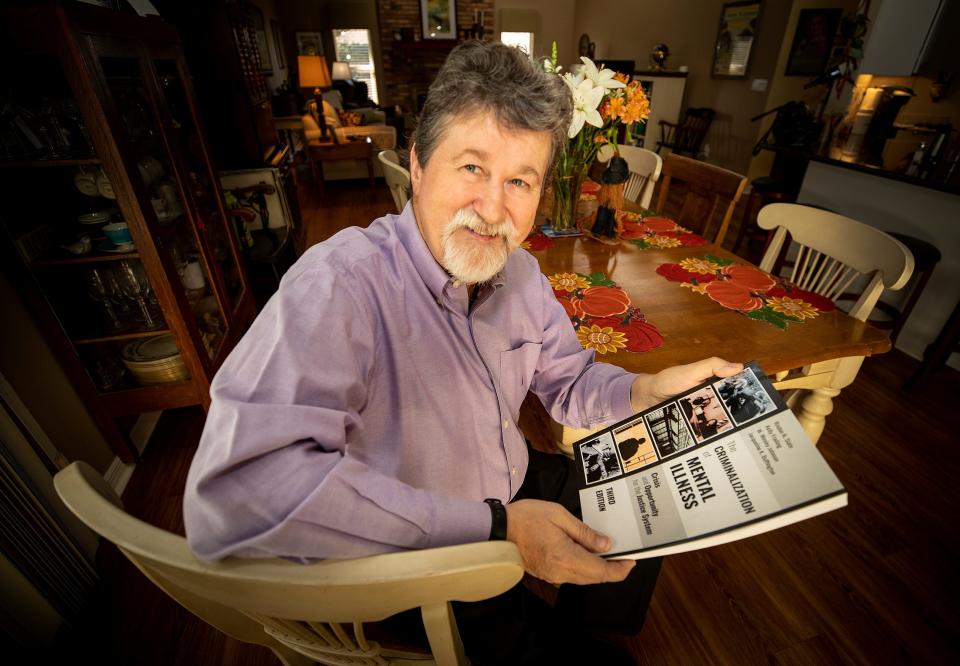

LAKELAND — Risdon Slate is, by all accounts, a pillar of the Polk County community, a college professor who advocates for the decriminalization of the mentally ill and helps to train law enforcement officers in how to deal with someone having a mental health crisis.

He also has a serious mental illness — bipolar disorder.

In addition to being a criminology professor at Florida Southern College, Slate, 62, has testified before the United States Congress and Florida Legislature about the poor job society does in taking care of the mentally ill.

“The mental health system is more than happy for the criminal justice system to have to deal with all of society's ills regarding mental illness and mental health,” Slate said. “I think we need a better mental health system and I think we need better linkage to mental health treatment — somebody should not have to commit a crime to get adequate and appropriate mental health treatment.”

Slate said people don't get access to mental health providers due to lack of insurance or money, or they simply don’t know where to begin to find a counselor or psychiatrist.

"They can't navigate proper access to mental health treatment until they do run into a problem with justice authorities and then the authorities, it's up to them to try to determine if they can be linked to treatment,” Slate said. “And maybe at that time, by that time, they've done something so severe they can't be linked to proper treatment in the community.”

Slate knows all this from firsthand experience.

Stories in series: Mental health in Polk County and Florida: Read every story in our series

Bipolar

In the 1980s, when he was in his mid-20s, he developed bipolar disorder, a condition that the National Institute of Mental Health says can cause unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, concentration, and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. It can sometimes require hospitalization and usually requires lifelong treatment.

“People experiencing manic episodes feel extremely elated, jumpy, or irritable. They talk very fast about a lot of things, and have racing thoughts,” the NIMH website states. “Depressive episodes include feelings of sadness, tiredness, sleeping too much or having trouble falling asleep, having trouble concentrating or making decisions and feel unable to do simple things.”

Slate's bipolar symptoms first presented as sleeplessness. At the time, he was working in a South Carolina prison as the warden’s administrative assistant and they were dealing with two executions within one year for the first time in decades. He went to his family physician, who misdiagnosed him as having “situational depression” and put him on amitriptyline, an antidepressant. At one point he stopped taking it, but then began experiencing the sleeplessness again and went back on the medication. He also changed jobs and began working as a federal probation officer, during which he had a stressful event with a parolee.

Within a few weeks, he was arrested in Miami after self-medicating with alcohol for a few days and getting into an argument with a man in a hotel bar.

“I go to the bar and start drinking and I encounter a man at the bar who I envisioned to be my father,” Slate said. “I know he's not my father, but I think he's playing the role of my father — I think I’m on a film set — and so I start interacting with him as if he's my father and my father and I didn't have a good relationship. So before you know it, we're in this argument.”

The police showed up and he was taken to Jackson Memorial Hospital, where he was tied to the bed as he screamed for help because he thought spiders were lowering themselves onto him. His wife was tracked down at the hotel and she was allowed to take him home to Columbia, South Carolina, where he was hospitalized. Within two weeks, he was forced to leave his job as a federal probation officer and his wife announced she was divorcing him.

His psychiatrist, Dr. Roger Deal, helped him cobble his life back together, diagnosing him as bipolar and putting him on appropriate medication. He also told Slate that amitriptyline was the worst medicine he could’ve been prescribed

“He said it blows the mania out the top of your head — he said it's like putting jet fuel on the fire,” Slate recalled. “So, you've got a mistake by family physician. And who prescribes most of the psychotropic medication in the United States? Family physicians. And they're getting it from these pharmaceutical reps that are pushing it, of course.”

Slate got a job teaching at a community college and eventually earned his Ph.D. in criminal justice. He began teaching at Florida Southern College, but then another doctor in Lakeland made a critical mistake in his treatment.

“After about four visits with this psychiatrist, what does he decide? He decides I’m not mentally ill,” Slate said. “He said, ‘You know what I think? You had a brief reactive psychosis to a stressful event.’”

![Chairs line the parade route in Downtown Lakeland on Tuesday, December 4, 2018. Though the annual Lakeland Christmas Parade isn't until Thursday evening, people loaded up their truck and vans with chairs and trekked downtown to stake their claim on the best viewing spots in town. [Laura L. Davis/The Ledger]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/dALUsLJM2Q.iH1eUpuQqgw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-ledger/ccd4db283af632539c774e56714a35ba)

Final psychotic episode

And then he gave the green light for Slate to stop taking lithium. Within two months, Slate had another psychotic episode when he was in Columbia, South Carolina, for the first time in eight years on Labor Day weekend of 1994.

"I'm at a football game with my new wife and I'm, I'm literally so delusional I think I can control the players on the field – the South Carolina Gamecocks - and make them run over the Georgia Bulldogs and it will make them win the game,” Slate said.

When his mind control didn't work, he became frustrated and he and his wife left the game. Then paranoia set in. He began wondering why he had been forced out of his job and lost his first wife if, like his new doctor said, he wasn’t mentally ill.

"I started thinking that - not rationally, but thinking – well, then there must have been some sort of collusion between a federal judge, my federal probation officer supervisor, my wife's father — who didn't like me — and even maybe my wife,” Slate said. And they were all in on it and three of them were in Columbia, so I needed to go undercover.”

His “undercover investigation” involved skinny dipping in a condominium pool – twice. The first time, police told his wife, who was not involved in his nighttime swim, to keep him inside. The second time, she begged them for help.

“She said, ‘Look, this guy has a Ph.D. in criminal justice. This guy worked in this town as a federal probation officer and he worked at the prison as an administrative assistant to the warden. He is mentally ill. He's bipolar. A doctor took him off his medication. Please help him,’” Slate said. “Their help for me? They took me directly to jail. They didn't bother telling anybody in jail the conditions that I was under and experiencing.”

He said jail guards beat him when he resisted being moved to a solitary confinement cell designed for mentally ill inmates. He described the beating as an out-of-body experience and does not remember feeling any pain, although he has photographs of the bruising.

The only thing in the cell was a hole in the floor that served as the toilet. In his psychosis, he put his hand into the sewage hole and began “fishing” around. He had read a book in college about an indigenous medicine man and his memory of that inspired him to smear human excrement on his face as war paint and begin dancing around in the cell.

He also found a former inmate’s broken wristband in the hole.

“I thought, ‘Man, they killed somebody in here. They killed whoever this guy is whose wristband is in here. They’re gonna kill me,’” Slate recalled. “And so I started freaking out. Hair started standing up on the back of my neck."

He said at that moment, the cell door opened. A former co-worker at the federal probation office, Ron Hudson, heard what was happening and arrived to take Slate to a psychiatric facility.

“Ron came down to that jail, under no authority whatsoever, and he told the jail, ‘You’ve got Risdon Slate in here. He's coming with me,’” said Slate, who credits Hudson with saving his life that day. “I think they were glad he came to get me because they didn't know what in the hell to do with me.”

He was hospitalized, placed back on his medicine and has not had another incident. He said he took lithium for 30 years, but, because it can do kidney damage, he is now on the generic form of Depakote.

Slate spoke recently at his Lakeland Highlands home as he sat by his swimming pool on a beautiful autumn day, his dog, Teddy, by his side and his wife, Claudia, on her way home from an errand. Their house is decorated with both Union and Confederate memorabilia, along with framed quotes from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Several years after the final South Carolina incident, he testified before Congress about his experience and also to the Florida Senate Committee on Health Care in 2005, urging them not to implement a preferred medication list, which stipulates that only certain medicines can be used to treat people on Medicaid or in jails and prisons. Slate said that can complicate treatment and even cause people to slip back into psychosis because it can sometimes take months for a patient to find the right medication.

Slate puts a brave face on mental illness because he wants people to know that there is treatment and people can live a fulfilling life.

"I have made a conscious decision that I'm no longer ashamed or embarrassed about having a mental illness,” Slate said. “What I am embarrassed about is how we treat people with mental illness within our society. There needs to be formal structures put in place to help people.”

To get help

Polk County's Peace River Center offers a 24-Hour Emotional Support and Crisis Line: 863-519-3744 or toll-free at 800-627-5906

Ledger reporter Kimberly C. Moore can be reached at kmoore@theledger.com or 863-802-7514. Follow her on Twitter at @KMooreTheLedger.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: FSC criminology professor advocates for decriminalizing mental illness