Memorial Day: Remembering soldiers who gave all, came home in flag-draped coffins

I can see the tombstones of First Sgt. Robert Peck Hocker Jr., my father-in-law, and Pvt. First Class Hershel Jewell Stephens, no relation, from the back door of our house in Arlington, Ky.

They’re buried near each other in the town cemetery.

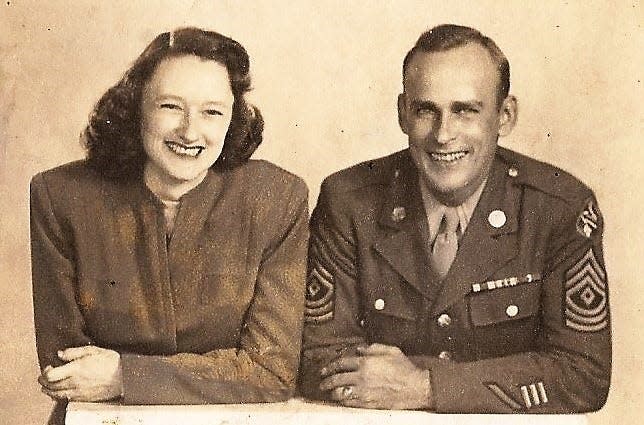

Stephens and Hocker were soldiers. Both left young wives when they went off to World War II. Both fought in the Philippines.

I don’t know if the two GIs knew each other. Stephens was from nearby Columbus, Kentucky.; except for his Army service, Hocker lived all his life in Arlington.

'Dearest Mom': Letters home from a Kentucky World War II soldier illuminate life at war

“You know, I had a dream,” says Al Stephenson, the returning Army sergeant character Fredric March plays in the classic movie, "The Best Years of our Lives." “I dreamt I was home. I've had that same dream hundreds of times before. This time, I wanted to find out if it's really true. Am I really home?”

He's home in the film, reunited with his wife, his children and his old job at the bank.

Hocker, Stephens and millions of other real veterans—including my sailor father, Berry Craig Jr.--had the same dream, especially when they were facing violent death from powerful enemies far from home.

Hocker made it home to western Kentucky. So did Stephens, in a flag-draped coffin and more than three years after he “gave his life for his country at Luzon P.I. in World War II Feb. 21, 1945,” according to the epitaph chiseled on his rectangular gray tombstone in the city burial ground. Besides his wife, Katherine Stephens, he was survived by a daughter.

Hocker’s birthday was Nov. 13, 1913, about nine months before World War I started. Stephens was born on April 12, 1918, seven months before the end of the global conflict that was supposed to “end war” and “make the world safe for democracy.” It failed on both counts.

We call the Great War “World War I” because there was a World War II, now the deadliest and most destructive war in history.

More: Traveling for Memorial Day? Here's when to avoid hitting the road, according to experts

“When the war ended, more than twelve million men and women put their uniforms aside and returned to civilian life,” Tom Brokaw wrote in "The Greatest Generation." “They went back to work at their old jobs or started small businesses; they became big-city cops and firemen; they finished their degrees or enrolled in college for the first time; they became schoolteachers.”

Nearly 417,000 Americans died in their uniforms, according to the National World War II Museum. Most like Stephens, 26, were young.

Hocker returned to his family store, which turned 125 years old last month. (My father played minor league baseball). Married for 56 years, Hocker and his native Mississippian spouse, Mary Helen Parrish Hocker, reared a son, Robert III, who runs the family business, and a daughter, Melinda, a retired school teacher and my wife of going on 44 years. We live in the 1880s vintage Hocker homeplace.

Stephens evidently was buried in the Philippines and then reinterred in Arlington.

Hocker, who also fought on Iwo Jima, died in 1997 at age 84. (Mary Helen died in 2019 at age 98.)

Arlington’s H.C. Lamkin American Legion Post 250 was in charge of Private Stephens’ military funeral rites. Hocker was a longtime post member who participated in many such rites. We don’t know if he was in Stephens’ burial detail.

But the burials of these two soldiers—one young, the other old—a half-century apart brought their parallel lives full circle. They left loved ones from the same part of the country. They battled the same enemy in the same place, and they are buried in the same place.

In my 45-year career as a historian-journalist, I have interviewed many World War II veterans for articles and books. All of them are gone.

In the introduction of his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1984 book, “The Good War: An Oral History of World War II,” Studs Terkel quoted a 30-year-old-Washington, D.C., woman who said she couldn’t “relate to World War II. It’s in schoolbook texts, that’s all….Or costume dramas you see on TV. It’s just a story in the past. It’s so distant, so abstract. I don’t get myself up in a bunch about it.”

Terkel said the woman was “doing just fine.”

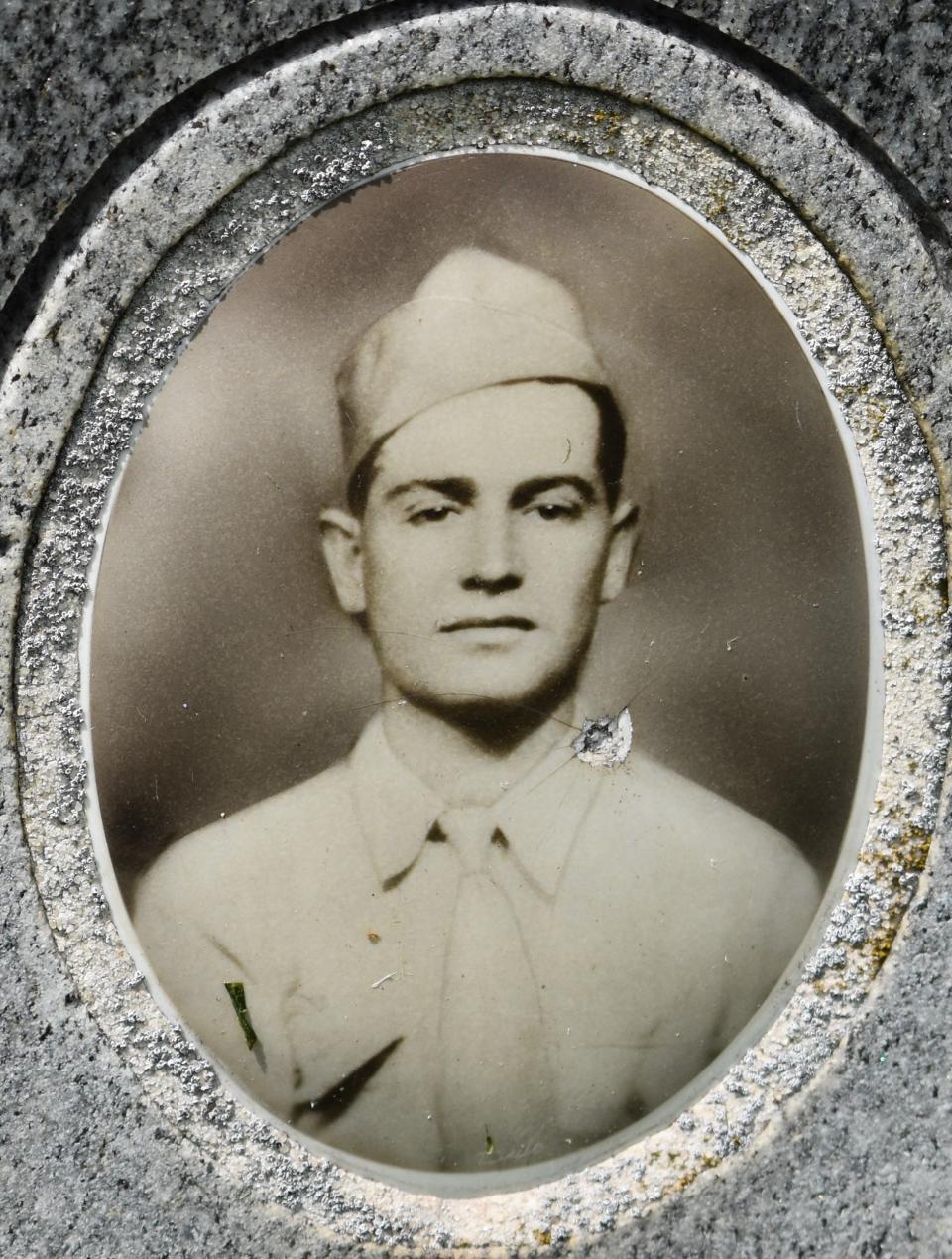

A Japanese bullet, or bomb or artillery shell denied Hershel Jewell Stephens his chance to do “just fine.” The small, cameo image of him in uniform fastened to his tombstone is no abstraction.

Sixteen million is such a huge number that it might seem abstract. But it’s how many American men and women heeded what Brokaw described as "the call to help save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs.”

I’m remembering them all this Memorial Day, but especially First Sgt. Hocker, PFC Stephens and Motor Machinist's Mate First Class Craig.

Berry Craig is a professor emeritus of history at West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of several books on Kentucky history including Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Memorial Day: The soldiers who came home in a flag-draped coffin