What makes the Rosetta Stone so special – and why it could be time to return it to Egypt

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For an item which has existed for more than 2,200 years – and was largely forgotten for around 1,400 of them – the Rosetta Stone has a wonderful capacity for making headlines.

And although it has barely moved in the last 220 years – there it sits, as we speak, in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery of the British Museum – it is again a matter of heated debate. Not bad for what was effectively a government press release, ignored by most who saw it.

Not that the conversation around this most precious of artefacts ever cools down. This has been reemphasised this week with the launch of two petitions calling for its repatriation to its birthplace, Egypt. One comes from Zahi Hawass, the country’s former Minister of State for Antiquities, who has been at the forefront of Egypt’s battle to protect its heritage for much of this century. The second, the work of Monica Hanna – the dean of the Alexandria-based Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport – makes its case in clear and angry terms. “The British Museum’s holding of the Stone is a symbol of western cultural violence against Egypt,” the respected Egyptologist has said.

If the debate around the Stone has long been heated, perhaps it just became a little hotter.

From here, the conversation usually runs along established lines. A back-and-forth about the appropriateness and viability of Asian, African and Middle Eastern treasures still being stationed in the cavernous museums of London, Paris, Berlin and New York in the early decades of this new millennium. The well-rehearsed response about the major cities of the West being the perfect places for guarding these treasures, ensuring their safe-keeping in state-of-the-art institutions, where millions of people can admire them at a respectful distance. The counter-argument that such a stance is not only patronising, but increasingly redundant, as epic museums spring up in the countries from which said treasures were taken – the Acropolis Museum that opened in Athens in 2009 (in Europe, yes, but still missing the “Elgin Marbles” it cherishes so dearly); the Grand Egyptian Museum, which is set to be inaugurated on the outskirts of Cairo next year. Finally, the standard hand-wringing and obfuscation – mutterings that repatriations require government action and legal frameworks – until all talk subsides for another year or two.

But this time, the conversation may have a different tone. The straight-bat defensive tactics that cultural authorities have relied upon before are no longer the default position. In 2019, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art returned the Coffin of Nedhemankh – a gilded marvel of the second century BC which once held the mummy of a high priest – to Egypt after it was proved that it was looted during the political turbulence that brought down President Hosni Mubarak in 2011. And earlier this week, London’s Horniman Museum announced that it was handing back 72 items to the Nigerian government, including the fabled “Benin Bronzes”. Most of these artefacts were seized by British soldiers in 1897, during the destruction of the royal palace in what was then the Kingdom of Benin. A new Edo Museum of West African Art is due to open in Benin City in 2026.

Will the cutting of the red ribbon at the Grand Egyptian Museum – which has been under construction since 2012, and is now several years late (its “imminent” opening was first mooted in 2019) – see the Rosetta Stone transported back across the Mediterranean? Almost certainly not. But its location has rarely been more in question. “It would be great to have the Rosetta Stone back in Egypt, but this is something that will still need a lot of discussion and co-operation,” Dr Tarek Tawfik, the museum’s director, said in 2018. Four years on, and with the project he is responsible for finally about to come to fruition, his call will carry more weight than ever.

There is, of course, an emotional, moral side to the debate: Can it ever be right for one country to hold onto another’s cultural treasures, especially those considered “sacred”? But a pivotal part of the Rosetta Stone issue is whether its initial removal from Egypt can be considered legal. Hanna’s petition refers to the artefact as a “spoil of war”. The British Museum maintains that it was removed fairly, and with permission; the 1801 agreement which allowed for the Stone’s transfer to London features the signature of an Ottoman admiral who had fought alongside British troops in their regional battles with French forces. Egypt was, at the time, under the hegemony of the Ottoman Empire. Hawass counters that Egypt was occupied in 1801; that it had no say in the Rosetta Stone’s future.

Even deeper, at the very core of the matter, is one pure, essential, unavoidable truth. That the Rosetta Stone is remarkable – and that it changed our understanding of the ancient world. There is not a museum on the planet that would not want it as part of its collection.

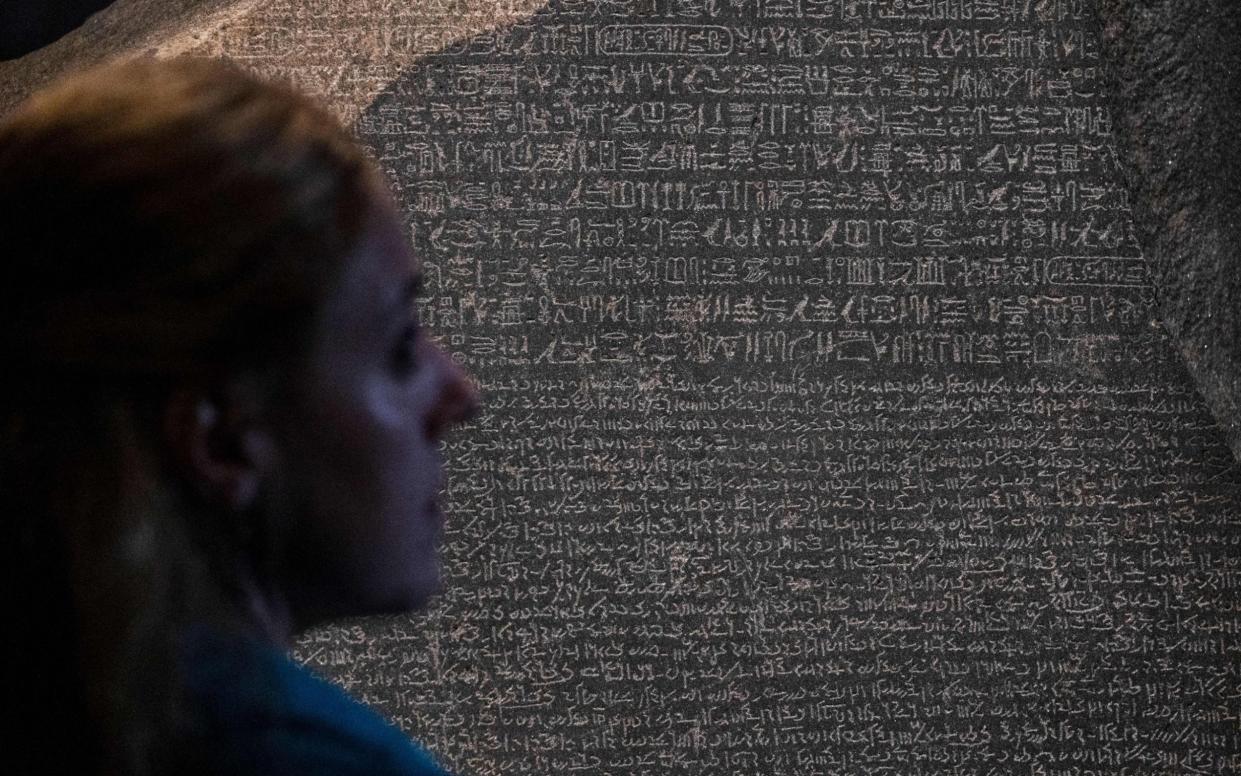

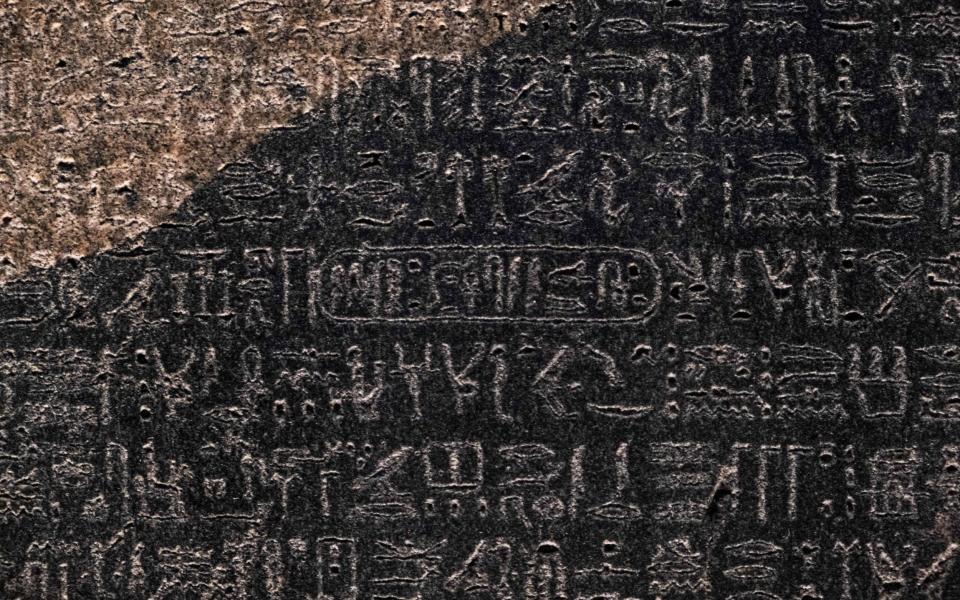

It has been the star attraction at the British Museum pretty much from the moment it was installed in 1802. It is nothing less than a touchstone of linguistic translation – a metaphorical Tower of Babel in reverse, if you will. The basic physics are simple – the Rosetta Stone is a lump of granodiorite (a type of igneous rock similar to granite), just over a metre tall. But it is the words inscribed upon it that are of such importance. The script it bears is in three different languages – Egyptian hieroglyphics, Demotic script (a written form of the Egyptian language that was used in documents from around 650BC to the fifth century AD), and ancient Greek. That the message it conveys is (largely) the same in each tongue – direct translations of each other – is what makes it invaluable. Its discovery in 1799 would unlock latter-day understanding of hieroglyphics, and spark a great broadening in modern knowledge of life and ritual in the Egypt of distant centuries.

In this context, its actual message, thrice-stated, is something of a side-show – although a side-show that acts as a fascinating window onto the state of Egyptian politics in 196BC.

In the year the Stone was carved, Egypt was ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty; a line of pharaohs of Greek-Macedonian descent (hence the use of ancient Greek) which had held sway since 305BC (and would continue to do so until the Romans arrived in 30BC). The Stone finds them almost midway through their time in power, with the fifth ruler of their bloodline – Ptolemy V Epiphanes – on the throne, but struggling to assert his authority.

With good reason. Although he had been the monarch for eight years by 196BC, he was just 14 years old. His father, Ptolemy IV Philopator, had been assassinated in 204BC, with the killers taking charge for part of a subsequent decade of regency and chaos. The Rosetta Stone was an attempt to shore up his position – a decree, issued by priests at Memphis (the ancient Egyptian capital), possibly on March 27, which threw the intellectual weight of the religious hierarchy behind the young man and his right to rule. It was a statement which sought to quell a period of uncertainty. Thus it was issued in three languages, to ensure it was read, and comprehended, by as many people as possible.

It would be more accurate to describe this missive from the crown as the “Memphis Stone”, or perhaps the “Sais Stone”. Its accepted name is an accident of history. “Rosetta” – also known as “Rashid” and “Rasheed” – is a port on the Nile Delta, just inland from the Mediterranean, 40 miles north-east of Egypt’s second city Alexandria. It was here that the Stone was found on July 15 1799, by French soldiers conducting renovations on Fort Julien – an Ottoman stronghold that, although in a state of disrepair, had been seized at the beginning of Napoleon’s notorious invasion of Egypt a year earlier.

The fort had been built in around 1470, partly using blocks from ancient sites. One of them may have been nearby Sais, 45 miles upriver, where academic opinion believes the Rosetta Stone might have stood in a temple, If so, it would have been condemned to dust and decline in 391AD, when the Roman emperor Theodosius I ordered the closure of all non-Christian places of worship. Whatever its precise route to Fort Julien, it was spotted by Lieutenant Pierre-François Bouchard – who immediately realised that it might be a great discovery. Work was stopped, the Stone was salvaged – and its modern story began.

Bouchard’s sharp eyes plunged the Stone into an era of turmoil every bit as troublesome as the Egyptian dynastic crisis in which it had been conceived – the Napoleonic Wars. By March 1801, British forces had landed on the Egyptian coast at Aboukir Bay, and by early summer, Alexandria – and the French troops within it – was under siege. As was the Rosetta Stone. The city fell on August 30, and after a spell of nervous negotiation and vociferous recrimination, the Stone was surrendered to British hands, spirited away from the possession of Jacques-François Menou, the French general – perhaps by gun carriage.

France knew what had been lost, but with the Ottoman authorities in Egypt siding with the British, was powerless to prevent the transfer. The final insult was that the Rosetta Stone was conveyed to the UK on a captured French vessel, the HMS Égyptienne, which had delivered its rare cargo to Portsmouth by the February of 1802. It was installed in the British Museum, on the orders of George III, as early as March 11 1802. And it has remained there ever since, excepting the single month that it spent on loan at the Louvre in Paris in (October) 1972 – and its years stored underground during the two World Wars.

During that time, it has been scanned and studied, perused and probed. Not just by historians, who have wrung deep meaning from its inscriptions, but by thousands of 19th-century museum-goers, who were allowed to lay fingers on what craftsmen had created 20 centuries previously. It was not until 1847 that the Stone was placed into a protective frame. Since 2004, it has been displayed in a glass case in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. A replica, in the King’s Library, allows visitors to touch the “Stone” as the Georgians did.

Will this ancient wonder still be in the British Museum in 10 years’ time? In 50? In 100? It would be foolish to make predictions. But if you have not yet seen the Rosetta Stone, you certainly should. It is a conduit to ancient yesterdays, pulling us back through two millennia, to an era of gods and pharaohs. And it always will be – wherever it is on show.