Literary Mood Board: The delightfully obscure items that inspired Anthony Doerr's Cloud Cuckoo Land

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Courtesy Anthony Doerr; Simon and Schuster Anthony Doerr; 'Cloud Cuckoo Land'

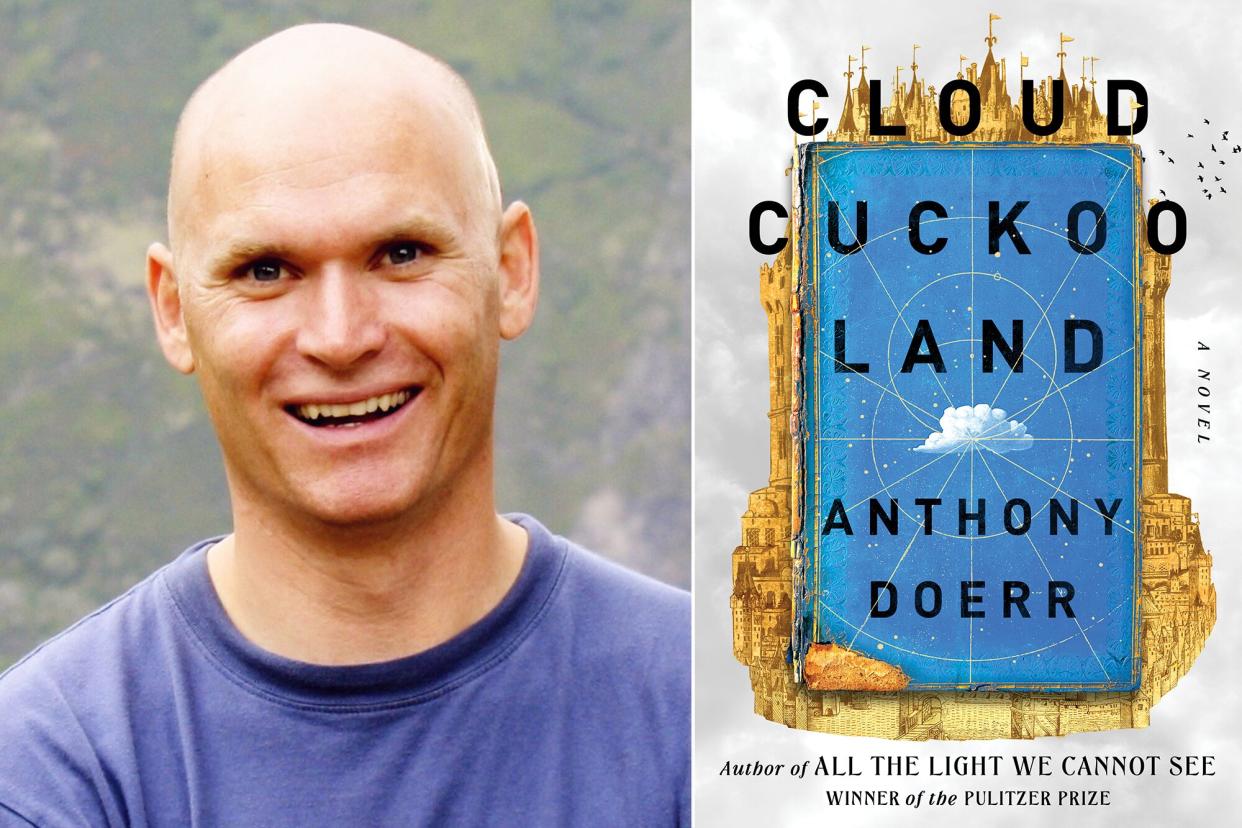

Anthony Doerr has made a name for himself — and won the Pulitzer Prize — as a master literary world-builder. His 2014 novel, All the Light We Cannot See, allowed readers to immerse themselves in World War II–era Europe, and his latest release expands on his skills to truly epic proportions.

Cloud Cuckoo Land (out now) weaves together three timelines: 15th-century Constantinople, where a young Omeir joins a caravan on the way to invade the walled town and a 13-year-old Anna discovers an ancient and mysterious book; current-day Idaho, where a group of children prepare a stage adaptation of the book and a troubled teenager plots an environmental protest; and in the future, when a spaceship carries citizens to a new planet where they hope to escape the climate change–ravaged Earth. Doerr has a vast imagination, but he's also a scholar of — well, everything. Here, he shares with EW a few of the elements that offered him inspiration and helped to create the Cloud Cuckoo Land universe.

Constantinople

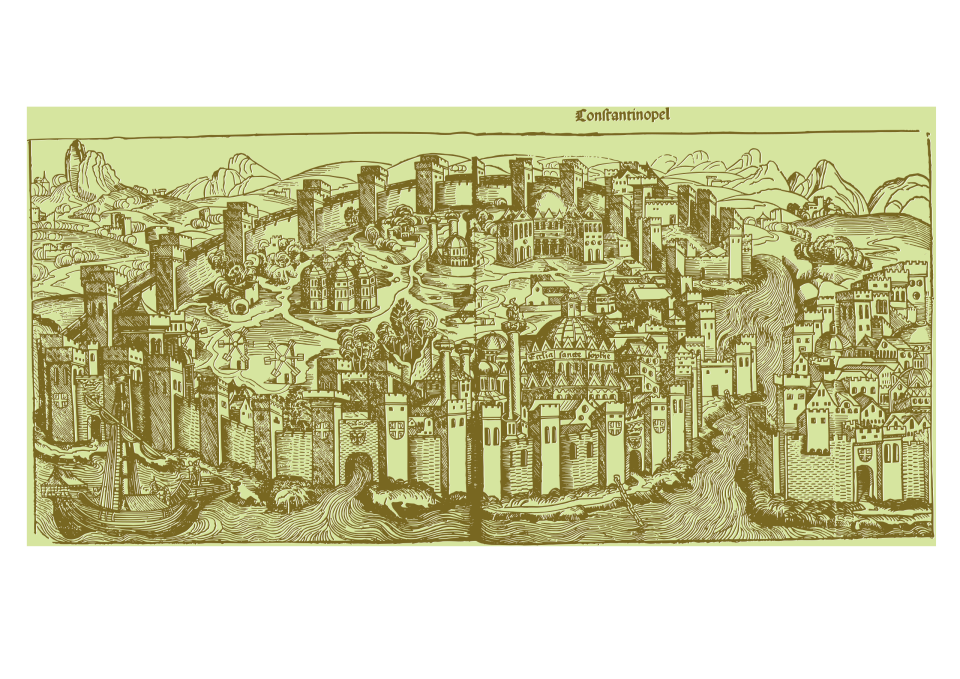

Courtesy Anthony Doerr Constantinople in 1493

"This map is from 1422 (the novel takes place in 1439-1452), and I found it while I was writing All the Light We Cannot See, during my research of defensive walls. All the Light takes place in the walled city of Saint-Malo, and everything I read about mentioned Constantinople — how advanced the walls were, how no army had ever breached it despite multiple sieges. It wasn't until gunpowder showed up in Europe that anyone was able to. So I bought this little print off Art.com or something and kept it as a reminder that I wanted to learn more about it. It's so fascinating: because of the way human memory works, and the number of years the wall existed, they started to believe that it was God who built it. It all took on a supernatural power, and I knew I wanted to tell that story.

"I was really inspired by the book culture of the Constantinople era. Inside the town there were some of the first lending libraries of human culture. We don't know too much about it because the huge Imperial Library burned several times, but we think that at certain times it had some 120,000 volumes. Because the wall stood for so many years it also kept the earliest versions of books safe; it's really crazy to me that this big defensive technology meant to prevent war somehow protected culture and stories, too.

"A book in itself is an amazing technology. Before the codex was invented everything was on scrolls, but the book allows you to store so much inside of it. It allowed a record of things that outlasts all of us. The fact that I can die and give this book I have in my hands now to my kid is an astonishing thing. This is how I came up with [protagonist] Anna: thinking about how people would say, 'I guess I'll just read The Odyssey again because it's the only book I own.' I wanted a character who loved stories that much."

All the Light We Cannot See

"All the Light was, at the beginning, about the radio. It's about how its invention disrupted Europe and the structures of power in the 20th century, and how Hitler and his armies used it for information — and disinformation. I wanted to do that again: to take a technology and use it as the launch for a story. Here, it's gunpowder. It disrupted warfare, and the Ottomans used it to bring down defensive walls. If they hadn't done that, maybe we wouldn't have gotten the Renaissance; their bringing down of the walls set off the black market for books, with refugees running books to Italy. Suddenly you have early Renaissance scholars reading Plato and Socrates, creating the flowering of art and literature."

Paper architects

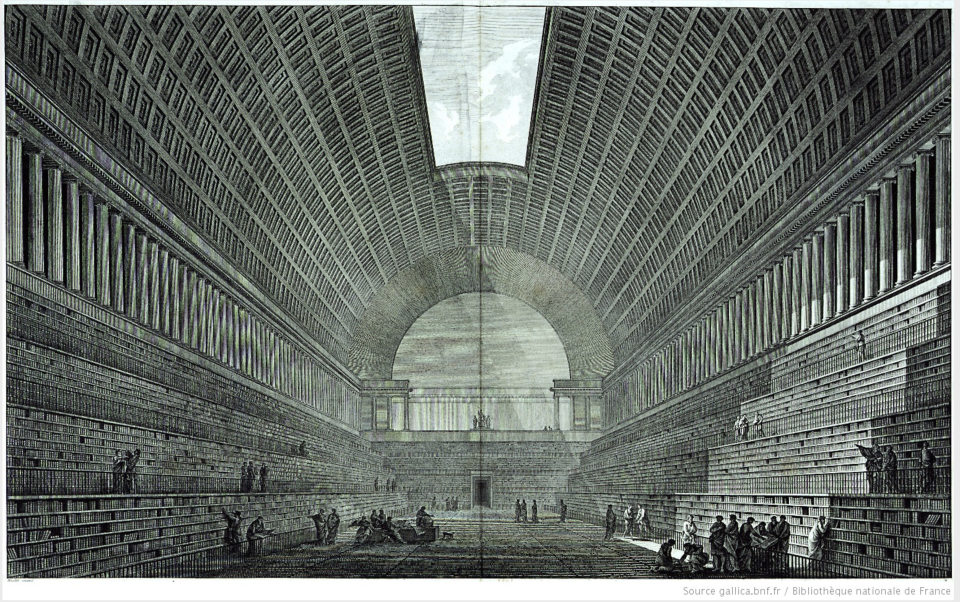

Courtesy Anthony Doerr An architect's design for a French library during the Enlightenment

"There's this whole world where architects draw buildings that could never possibly be built. I found a design that someone created for the French national library during the Enlightenment, with a big huge oculus in the ceiling and tiers and tiers of books. Konstance, the protagonist who lives on the spaceship [in Cloud Cuckoo Land], visits the virtual library, and my descriptions of it came directly from this. It's almost like the design is a vision of the internet, or the ultimate comprehensive library — which we could, of course, never really have. A library is a dream of imposing order on this disordered thing that's life, yet we always try for it anyway. During the Enlightenment, they were trying to bring wisdom to all people. What I'm trying to ask in the book is: Have we actually done that?"

Owls

"I play a lot with owls in the book. Here in Idaho, we're lucky enough to have these great horned owls come to our tree sometimes. They'll screech and scare the crap out of you, man. They're big and beautiful yet hard to find, and we're at risk of losing them, so I thought, 'Okay, I'm going to use the owl to dramatize the human connection to the natural world' — that happens in Seymour's section. I also use it to represent his lost father, maybe even a godlike figure. I decided to cram the imagery everywhere."

The Greek alphabet

"This book has three different timelines, with characters and elements interwoven, so I drew a structure of the novel and used it as I was writing. There are five main characters, and I used the Greek alphabet as the through line, going from Alpha to Omega: There are 24 letters and 24 sections in the book. And the book that gets passed on in Cloud Cuckoo Land, the book I made up, has 24 sections. It took me years just to get to this outline of the structure of the book. I used it as a big mood board to guide me through the writing process when I would get stuck."

Falter by Bill McKibben

Henry Holt 'Falter' by Bill McKibben

"I kind of surprised myself both in choosing to write part of this book in the distant future — I did that because I wanted to dramatize the survival of this ancient text as much as I could — and in how hard it was to write. It's not quite science fiction, but it took a lot of work to create the world. I don't know what space looks like — I don't know what they would be eating on the ship or what the kitchen would look like. But I did a lot of research, and a lot of it was about what the world is going to look like. Bill McKibben is a wonderful environmental writer, and even though the title sounds a bit pessimistic, it's more about the idea of what it will look like in 2100 when Miami is underwater, and maybe London is underwater. It helped me envision what the state of the planet would be like in that section of the book."

Cloud Cuckoo Land is out now through Scribner.

Related content: