You know the bridge. But how much do you know about Charles Braga and Pearl Harbor?

Charlie Braga was up early on this Sunday. He’d been out the night before with a buddy, meeting some local girls at the American Legion, but had been back home before 10 p.m. curfew. Charlie wasn’t a rule-breaker — he was a thoughtful young man, curious, soulful, responsible and sober-minded.

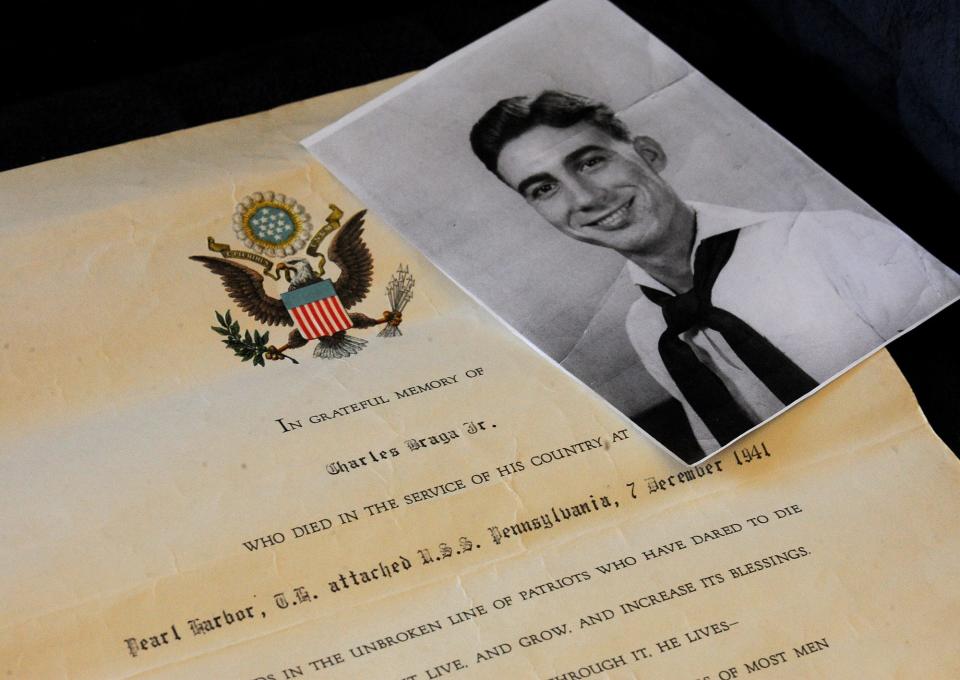

Charlie was a yeoman second class in the Navy, a 22-year-old Fall River man serving aboard the USS Pennsylvania — a battleship, and the flagship of the United States Pacific Fleet, a massive 600-foot vessel capable of carrying over 1,000 men. The ship was in drydock at the naval base in Pearl Harbor, on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, undergoing a refit.

The ship was Charlie’s home and had been for many months. He was a secretary in the ship’s executive office, and was spending the sunny morning of Dec. 7, 1941, delivering messages to the officers, walking along the Pennsylvania’s decks and through its narrow compartments. A Catholic, he often attended Mass on Sunday mornings but had a few errands to do first and planned to go later that day.

Leading Battleship Cove: 'Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity': Fall River's most unique museum has a new director

The United States wasn’t at war, and neither was Charlie. But war was on the horizon. To his west, across a vast 4,000-mile expanse of ocean, Japan under Emperor Hirohito had invaded China, and his troops were quickly conquering the rest of Southeast Asia and expanding farther into the Pacific. On the other side of the globe, Germany under Chancellor Adolf Hitler had invaded Poland two years earlier, then swept through much of the rest of Europe. Italy’s fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini had a foothold in Africa. Hitler’s Nazi troops had pushed east and were, around this time, making a play for Moscow and getting frustrated by extreme cold and snow.

In Hawaii, though, it was warm, a bright and clear day, and those were foreign problems. Charlie had arrived here in mid-January 1941, and spent much of the past year serving and conducting training with the fleet just outside Honolulu, one of the most beautiful places in the world. He documented his time there with photos of himself and friends in Hawaii, often writing in a journal. Sometimes he wrote poems.

"Here I am alone / with no one to call my own / As the hours go by / I weep and cry / For someone to hold me / And call me their own."

Just before 8 a.m., on Dec. 7, 1941, as Charlie walked through the ship delivering his messages, Japanese planes appeared overhead and bombs began to rain from the sky. There was no warning. After the first moments of chaos, when it became clear to the Navy crewmen and Army airmen that they were under attack, they rushed to their battle stations and defended themselves as best they could. There were dozens of U.S. ships and hundreds of aircraft in the base to protect, and for 90 minutes the Japanese bombers attempted to destroy them all. At 9:06 a.m., a bomb fell on the Pennsylvania and detonated inside a compartment Charlie had been walking through.

Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day 2019: What happened during the fateful attack in Hawaii?

The attack lasted an hour and a half, and left 18 ships sunk or grounded, 1,143 Americans wounded, and 2,403 Americans dead. Most of these were junior enlisted personnel — teenage boys. Since there was no declaration of war, they were all non-combatants.

Charles M. Braga Jr. of Fall River was among them. His body has never been found.

What kind of person was Charles Braga?

Charlie didn't have an easy life, like many Fall Riverites of his generation. He was born on March 19, 1919, and by age 3 his mother, Rosario, was dead of tuberculosis. The family lived in the Brightman Street neighborhood, first at 96 Brightman St. and later at 55 Morton St. His father, Charles Braga Sr., was an Azorean immigrant from São Miguel who worked as a weaver in one of Fall River’s textile mills. An older brother, Caesar, died at 10 of a brain hemorrhage. He had three other siblings, all sisters: Adrienne, Delia and Agnes.

He was 10 when the stock market crashed in 1929, ushering in the decade-long Great Depression, the worst period of financial ruin in the country’s history. The Bragas scraped by, and after his sophomore year at B.M.C. Durfee High School he left to work in Sagamore Mills to support the family income.

Despite the hardship, he kept up his spirits and a healthy lifestyle, and loved his family. He’d spend time hanging out by the Taunton River in his neighborhood. In a story from 1991, his older sister Adrienne told The Providence Journal, “He never smoked, never drank, and he was always laughing. He used to tease me a lot.”

Charlie endured a few years of the grind in the mill before he decided to leave his neighborhood in search of adventure: he’d join the Navy. After convincing his father to allow him to enlist, he joined in 1939, and set sail aboard the USS Herndon, a destroyer that operated in Guantanamo Bay and the Canal Zone.

Charlie was transferred to the Pennsylvania, which became the flagship of the Pacific Fleet and sent to Pearl Harbor to participate in training exercises and preparedness, in case it became necessary to engage the Japanese as they began their reign of conquest along the Asian Pacific coast. While there, Charlie, a talented marksman, was working to become a yeoman first class, and in October 1941 trained to become a Navy pilot. He would pass a series of pilot tests with a great score.

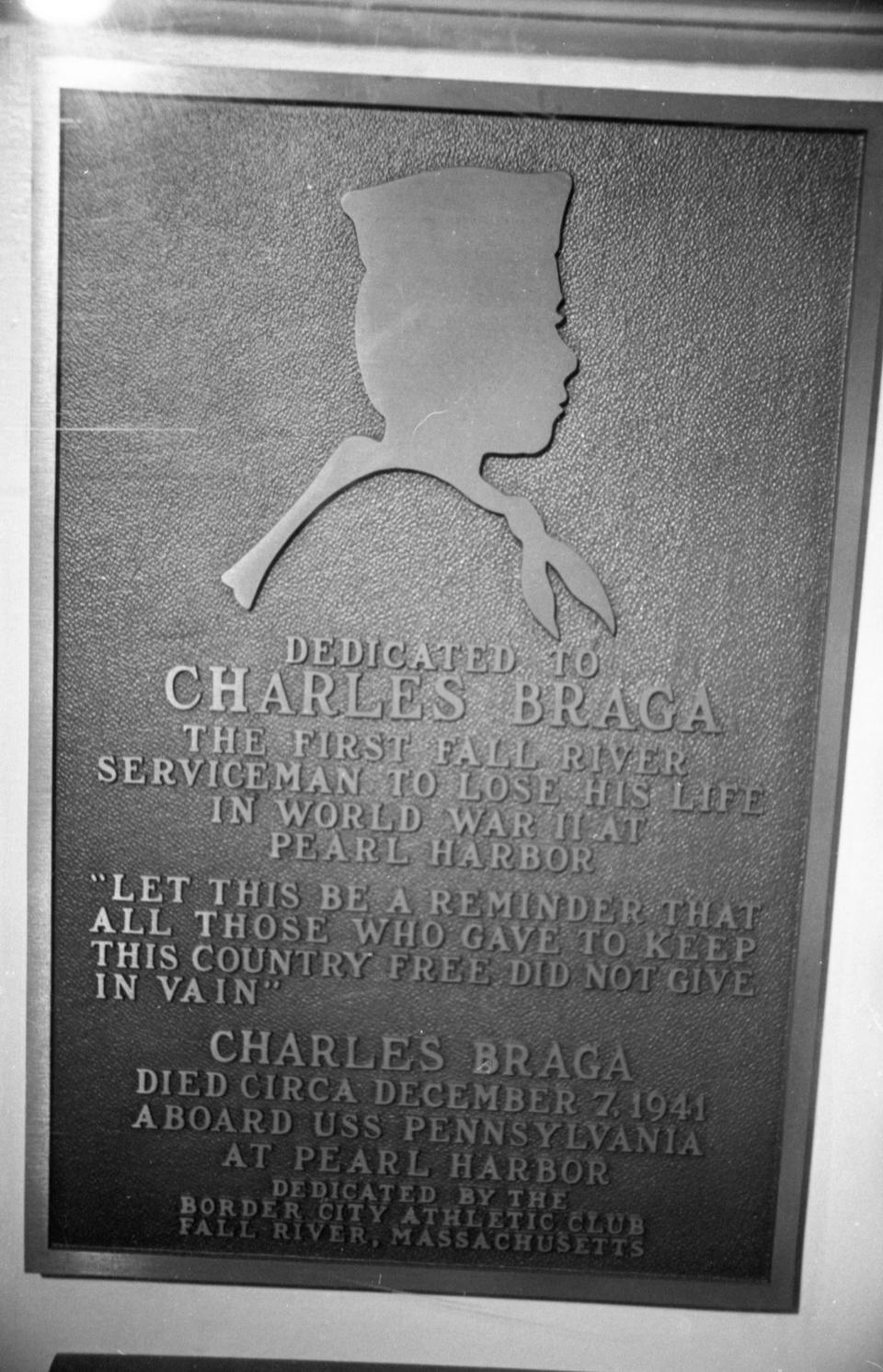

Less than two months later, he was the first Fall Riverite killed in “the new war” — what would later become known as World War II.

'Never forgive, never forget': 79 Decembers later, Pearl Harbor survivor's memories won't dim

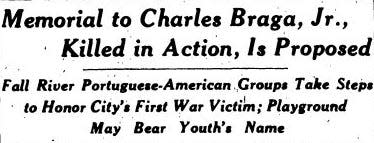

The struggle to give Charles Braga a fitting memorial

Immediately after word of Charlie’s death reached Fall River, efforts began to honor his sacrifice. But it would take a while to materialize.

“As much as we dislike war and all its horrors and destruction, we must always be ready to defend our country and its sacred honor,” said Msgr. John F. Ferraz of St. Michael’s Church at a requiem Mass for Charlie on Dec. 20, 1941. “Many other young men from this city as well as from other communities throughout the nation will surely follow him in offering their lives to their country in this great conflict.”

“The people of Fall River of Portuguese extraction today are sorrowed but proud,” stated Fall River Registrar of Voters Jose Silva, on Dec. 14, 1941. “We are sorry for the family of this boy who so willingly gave his life that we might live. But we are proud that he represented, in his act of heroism, not only America, but the Portuguese-American colony of Fall River.”

Silva endorsed the idea of naming a playground after Charles Braga, noting in 1941 that the city was then “filling in land behind Espirito Santo Church near Alden Street in the Flint section of the city, with the intention of converting the property to a playground.”

“It should be known as ‘Charles Braga’ park,” Silva said at the time. While that land was filled and the park built, it became known as Father Travassos Park, the name it still has today.

Another playground plan came along a few weeks later, in January 1942, when a movement began to build a park and beach in Charlie’s neighborhood, on the site of the Weetamoe Mill on Davol Street, which burned down in 1940. In mid-September 1945 — days after the war that began with Charlie’s death had officially ended — the Fall River City Council voted to take by eminent domain land bounded by Brightman, Lindsay, Monty and Leonard streets to build a park, playground and beach. That never ended up happening, either. Two of those streets no longer exist, and the area is now a tangle of highways that make up Routes 79 and 6.

Ten years after Charlie’s death, the question of how to honor him was the focus of infighting in Fall River politics. "Councilor Homer W. LeBlanc questioned Council President Edward H. Bowen on his failure to name a committee to select a suitable site for a memorial to Charles Braga,” wrote The Providence Journal on Oct. 10, 1951. “Bowen replied that he did not feel a memorial to a war hero should be made a political issue.”

The state Legislature took up the cause later that decade. Construction was set to start in 1960 on a new highway connecting Providence and Cape Cod — what would become Interstate 195 — and a bridge would need to be built over the Taunton River. In 1958, the state passed a bill introduced by state Rep. Gilbert Coroa, naming that span the Charles M. Braga Jr. Memorial Bridge.

Over half a decade and $25 million later, the Braga Bridge was built and opened to traffic on April 15, 1966 — over a mile long, six lanes wide, one of the longest bridges in Massachusetts.

“Just as Yeoman Braga gave his life for this country in which he believed and for the freedoms which we now enjoy,” said Chamber of Commerce President Sumner J. Waring during the 1966 dedication, “this bridge gives us renewed opportunity to come together and enjoy area prosperity in the years ahead."

Ever since, the imposing bridge — and Charlie Braga’s name — have become iconic, an indelible part of not just Fall River’s skyline but a symbol of the entire Southcoast region.

Not the only Fall River native at Pearl Harbor

Charlie Braga may be known as the first Fall River casualty at Pearl Harbor, but he wasn’t the only one.

Pvt. Donat Duquette Jr. of 301 Quequechan St., an Army soldier assigned to Fort Kamehameha on Oahu, was also killed that day 80 years ago. He was declared missing in action until his death at Pearl Harbor was declared official over a month later. Duquette has a small plaque in his honor at Stafford Square, at the corner of Quarry, County and Pleasant streets. Unlike the Braga Bridge, this monument is easier to miss. An engraving on the stone says that Duquette is the first Fall River native killed at Pearl Harbor — some have claimed that his death preceded Braga’s by a few minutes that day, though the provenance is unclear and may never be established definitively given the chaos of the attack.

Dozens of other Fall River native servicemen were featured in a listing on Dec. 14, 1941, as being definitely or likely in Hawaii at the time of the attack, including Stanley J. Faryniarz, who served with Braga aboard the Pennsylvania and barely escaped death that day himself.

Dan Medeiros can be reached at dmedeiros@heraldnews.com. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Charles Braga: Fall River bridge named after Pearl Harbor sailor