Jessamine Chan and Jennifer Haigh discuss the 'colossal accident' of writing their timely new novels

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Beowulf Sheehan; Joanna Eldredge Morrissey Jessamine Chan and Jennifer Haigh

Jessamine Chan and Jennifer Haigh didn't mean to write two eerily prescient novels. Chan started The School for Good Mothers, her electrifying debut about a new government watchdog program that punishes mothers who make parenting mistakes with time in a strict reform school, years before the Trump administration even took power. And Haigh's Mercy Street, which follows a woman working at a Boston health clinic that performs abortions as well as several men who dedicate themselves to protesting the facility, conceived of her novel during a time when Roe v. Wade was still (relatively) unthreatened.

But now both authors — Chan is a newbie, while Haigh is on her seventh book — are releasing their projects into an unimaginably heightened political landscape. Here, they meet for the first time (over Zoom from Chicago and Boston, respectively) to discuss the similarities in their work and the stakes they're up against.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: Both of these novels are quite emotionally fraught and guaranteed to incite reactions in readers for a variety of different reasons. How are you both preparing for or interacting with feedback on your novels?

JENNIFER HAIGH: This is my seventh book, and the first one was published in 2003 which was pre–social media, of course. So readers could reach you through your website, or some actually did send letters to your publisher if they felt strongly enough about something. With this book, because it deals with abortion, part of what made it hard to finish was anticipating dealing with people's reactions to the subject matter. It's a subject that everyone has an opinion about but most people know very little about it. It's what led me to the subject to begin with, but I know it will be jarring for some — some people will feel alienated by the book, while others will react in a really positive way.

JESSAMINE CHAN: I had to try really hard, while I was writing, not to think about what everyone's reactions would be to my book. I had to pretend that my parents and sister and closest friends wouldn't read it, that it was my secret Microsoft Word document. I've been trying to put aside the potential conversation around it, so that I could write the weird book I wanted to.

HAIGH: I really love the pairing of these two books because I think they both get at something really important, which is the judgment that is heaped on women — for being a bad mother or choosing not to be a mother at all. No matter what you do it's almost impossible to thread that needle, as a woman.

CHAN: I have to say, I feel so wildly intimidated, because I could only hope in my lifetime to write seven books. I'm still at the point of thinking, "Will I ever write a second book? I also really related to Claudia [the protagonist] in your book, and her feelings about having children. I came to the experience of motherhood pretty late, and I struggled with the decision. And one thing you did that I certainly couldn't figure out how to do was write from the perspective of the opposing side.

HAIGH: The thing I've learned over the course of writing all my books is that it's a little bit like being an actor in that you have to take each character's side when you're writing them. No matter how completely you disagree with what the character believes, you have to see the world through their eyes without judging. I've always thought of it as a loyalty question.

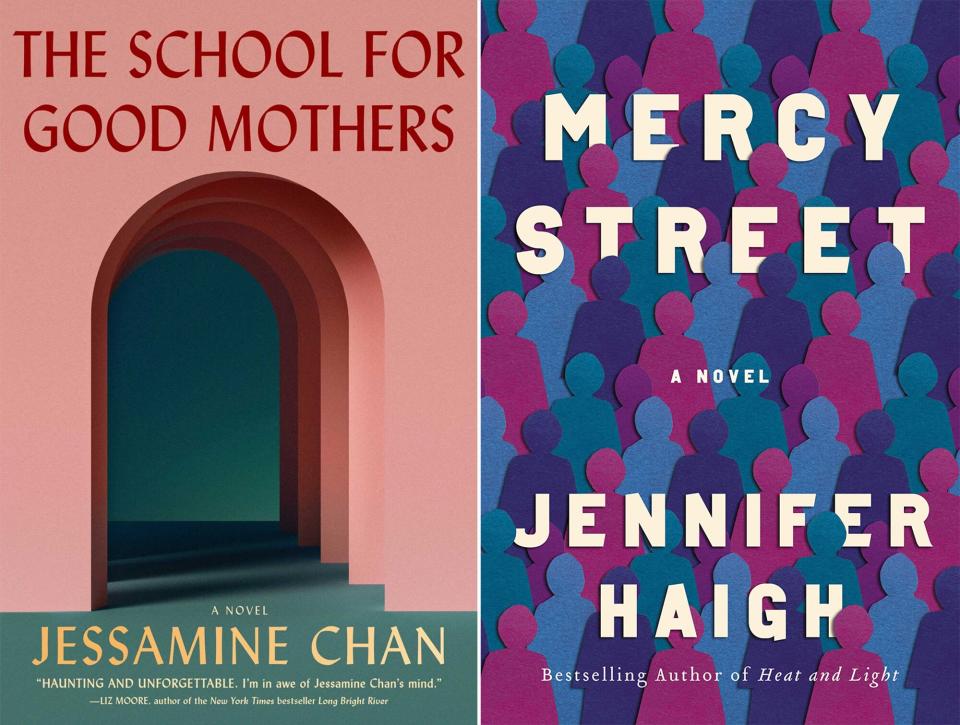

Simon & Schuster; HarperCollins 'The School for Good Mothers'; 'Mercy Street'

EW: What kind of work did you have to do to understand the villains in your novel, who are vehemently (and violently) opposed to the abortion clinic?

HAIGH: I understand way more about that than I would like to, because I grew up in Appalachia. My family is Catholic, and I learned that abortion was evil before I knew how you got pregnant. So I was very conversant with the arguments on that side. I grew up in a town where there are handmade signs along the roadway against abortion. As far as Victor [the character], I feel like I've known him my whole life.

EW: Both your stories are eerily topical, but I imagine that's not why you wrote them. What led you each to this subject matter, and why now?

CHAN: I started this project back in 2014, so it was a completely different landscape, politically. At the time my book felt much more dystopian than it does now. I had been trying to decide whether or not to have a baby, and I felt very panicked by the decision. My husband would bring up things like the melting of Greenland [laughs] — like, "How can we have a baby when the planet is falling apart?" And then I read a piece in The New Yorker called 'Where Is Your Mother?' by Rachel Aviv. It's this completely heartbreaking and tragic story of a single mom who left her toddler son at home for a number of hours and, after that day, never got him back. It details her whole Kafka-esque experience with the family court system, and I think it lodged in my brain and became the foundation for the book.

HAIGH: It takes so long to develop and write a book, that writing a timely novel is a colossal accident. That's the case with Mercy Street. I started volunteering at a women's clinic, not with any intention of writing about it but because I really believed in what they were doing. But I became so fascinated with the people who work at these clinics. To literally walk past a gauntlet of protesters when you're just going to work in the morning is such a difficult environment to face every day.

I worked as a volunteer on the hotline. People who want to schedule abortions, their first step is to call, and we'd explain the procedure and answer questions. So you're the first point of contact for women with these difficult decisions to make, and the moment I knew I was going to have to write about this experience was when a woman called the hotline and said, "If my ex finds out I'm pregnant he's going to come to my house and shoot me and my kids." I thought, "Okay, these stories need to be told." I've never really read anything true about abortion in a novel. It's such a third-rail subject that no fiction writer wants to go near it for obvious reasons.

EW: Something that struck me about both books is the way socioeconomic status comes into play. Jennifer, in Mercy Street you see how having wealth can offer women more choices, and Jessamine, in Good Mothers we see some wealthy women at the school come up against the realization that they can't buy their way out of their predicament.

HAIGH: That clinic was the most integrated space I've ever encountered in the city of Boston. Women from all sorts of backgrounds will find themselves in need of health care. But it lands differently for everybody. There's a high school–age character in the book who is in the process of applying for colleges and gets pregnant, and her mother comes with her to the clinic for support. But pregnancy can be a great equalizer.

CHAN: I actually chose to have my book not quite mirror real life, because I think in reality the upper-middle class white women probably wouldn't have even gotten in trouble — they wouldn't have caught the attention of CPS or would have gotten a really good lawyer and not been sent to reform school. But I wanted to draw attention to that. I was thinking about the neighborhoods I've lived in and how that affects mothers. When I lived in Brooklyn in a predominantly Black neighborhood there were police on every block. The mostly white suburb I live in now does not have police officers surveilling the community. I wanted to have my protagonist reckon with her own racial and class blind spots.

HAIGH: Something I was struck by in comparing our two books is that Jessamine's novel is a dystopian story that has become closer to our reality, and mine was written as a reality that is actually going to be a more positive spin on the access that women will most likely have. If things [in the Supreme Court] go the way they're seeming, Massachusetts and clinics like in Mercy Street are going to be the good examples. I wrote about these so-called crisis pregnancy centers, which are basically fake clinics that trick women into carrying their pregnancy past the legal cutoff, and these are vey real. There are hundreds of them in this country. There are researchers at the UC San Francisco who have been doing a project called the Turnaway Study where they look at what happens to women who are denied abortions, and the news is not good. The consequences to the women themselves are really dire to their mental and financial health. I could go on and on. Women are the best judges of whether or not motherhood is possible for them — we ignore women's judgments at our own peril.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free daily newsletter to get breaking TV news, exclusive first looks, recaps, reviews, interviews with your favorite stars, and more.

Related content: