Indiana's economy will fall off higher ed enrollment cliff. Did state set itself up to fail?

Editor's note: This story has been updated to more accurately reflect Ball State University’s 2023 financial aid estimates for in-state and out-of-state students.

While high schools across Indiana are educating more students than they have in the past two decades, the state's college enrollment is at its lowest in recent history. To many, such as the Indiana Commission for Higher Education, this leads to only one conclusion: Hoosier kids are no longer pursuing college degrees.

One local economist disagrees. Hoosiers are still attending college — just not in Indiana. And this will have huge, decades-long consequences for the state's economy.

The higher education enrollment cliff — a common prediction that the number of college students will plummet by more than 15% beginning in 2025 — has already begun across the nation. As fewer young adults go to four-year universities, the looming scarcity is kicking off a battle among U.S. states to claim those who are still enrolling.

Why do states care how many students go to college? A state's college attendance and job outlook often go hand-in-hand, feeding into one another in a continuous loop. Research has shown a person with even just some post-secondary education will earn higher wages and experience lower unemployment. Similarly, jobs with the highest projected growth by the Bureau of Labor Statistics are those that have some form of college degree, such as healthcare practitioners and equipment technicians. Meanwhile, jobs that are expected to decline — construction, manufacturing and security — typically require their workforce to have a only a high school education.

When technology giant Intel chose Ohio over Indiana to build its multi-billion dollar expansion, economist Michael Hicks opined Indiana lost that bid because businesses do not see a promising future in the state.

"We have great schools, but if we're not going to do things to get Hoosier kids to go to them and to stay here, (businesses are) just going to go to where the workers are," Hicks told The Herald-Times.

What's going on?As Indiana University's enrollment increases, Monroe County's presence on campus shrinks

As other states offer tuition breaks and scholarship supplements to in-state students, Indiana hasn't found a way to fight back. With state legislators cutting education support by "well over half a billion dollars, probably pushing a billion dollars now given in inflation-adjusted terms," Hicks said Hoosier kids are incentivized to attend out-of-state colleges, and most never return to Indiana to use their degree.

“Everyone has had a problem with this. The problem is that it is so much worse (here); we're so far behind that it's really damaged us,” Hicks said.

Lacking state funding, Indiana universities cater to out-of-state students for survival

When Hicks wants to illustrate how the higher education enrollment cliff impacts Indiana in real time, he recommends using an online tool such as a potential scholarship calculator that's typically offered on universities' websites. Hicks, a professor of economics and director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University, used his employer as a test in this instance.

Like many universities, Ball State has a scholarship calculator on its website where students can insert their GPA and test scores to see a potential amount of financial assistance. While these results are not official offers, they provide scholarship information based on a student's eligibility.

For an in-state student with a GPA of 3.5 and an SAT score of 1300, no financial assistance is identified by the calculator. However, if the user changes their status to living out of state, without changing their GPA or test score, they suddenly receive an annual $12,000. Even after adjusting their SAT score to 1000, the amount does not change.

Historically, if a student wanted to go to a university outside their home state, their tuition rate was more than what an in-state student would pay. Resident students are charged less because public universities are subsidized by state tax dollars. Given that out-of-state students come from families who haven't paid those taxes to the state, they are expected to pay more. While that difference in cost varies by state and school, out-of-state students are sometimes charged double or triple the amount of in-state tuition.

But that time seems to be over — and not just for Indiana.

"Every state's doing this: really promoting students (to go to) out-of-state universities. So the in-state, out-of-state tuition difference for a competitive student no longer is important," Hicks noted. "Hoosier students are being really wooed by out-of-state schools to go there because their families would be willing to pay in-state tuition to go to other schools."

In Indiana, more tuition breaks for out-of-state students goes back to a decades-long pattern of state funding — or the lack thereof.

Record-breaking enrollment:Indiana University will create 100 new faculty positions to keep pace with high enrollment

Between 2008 to 2018, Indiana's rate of spending for higher education has remained more or less flat, which is better than most other states, as noted in a 2019 report published by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. However, Indiana also has amongst the worst level of higher education funding, ranking in the bottom 10 of all states in public higher education appropriations per full-time equivalent enrollment during 2021, as recorded by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association.

In 2020, when budget cuts were spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, higher education was offered up on the chopping block. That year, the state Legislature reduced the total appropriation of more than $1.4 billion by about 7% for Indiana’s seven public university systems for the fiscal year 2021; it was later restored.

Meanwhile, from 2008 to 2018, Indiana's tuition rates at public, four-year universities increased by 16%. Those tuition costs are still rising each year.

The Indiana Commission for Higher Education reports 53% of 2020 high school seniors enrolled in college, which is 10 percentage points below the national average. Since 2015, enrollment has been dropping both statewide and nationally.

Monroe County residents can see this trend on a micro-level. About 62% of Monroe County students from the graduating class of 2020 enrolled in college, a 6% decrease from 2019. In 2019, 68% of local students enrolled in college, down from 73% in 2018. Each individual school with data published, including Bloomington High School North, Bloomington High School South, Edgewood High School, Bloomington Graduation School and Lighthouse Christian Academy, saw drops in that same time period.

“It's just a substantial cut in support for colleges across the state and that's what's driving the enrollment declines. The Indiana Commission for Higher Education says, ‘Oh, we're not doing a very good job of convincing potential students the value of higher ed,'" Hicks said. "That's not it at all. If that were the case, the first place you wouldn't go would be Notre Dame or Butler or Hanover (College). All these are very expensive schools and those schools are doing just fine. It really comes down to less support for education.”

With a lack of state funding, higher education institutions are now opening up spots for more out-of-state students.

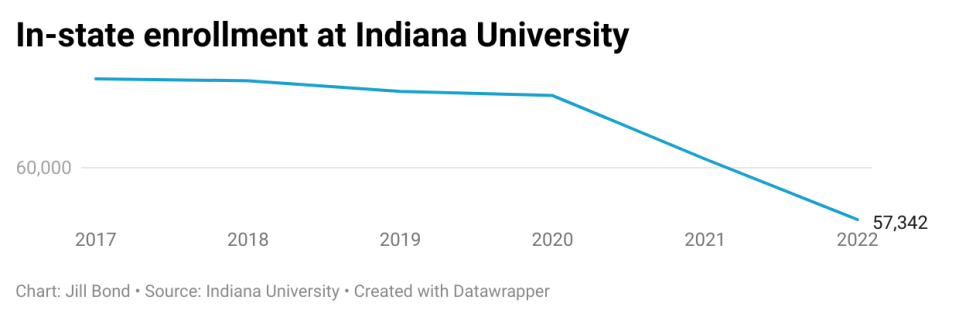

"If you look over the past 20 years, the number of in-state students that are going to IU, Purdue, Ball State, IUPUI has plummeted,” Hicks said.

At Indiana University, in-state enrollment was 70,859 students across all campuses in fall 2012. This semester, that number is now 57,342 students. Meanwhile, enrollment of students from other states increased from 15,198 in 2012 to 21,542 students in 2022.

With Hoosier students being lured away and with no financial incentive from the state for universities to pursue in-state students, many universities in Indiana are looking elsewhere to fill seats.

"(Indiana universities would) much rather just reduce the cost to an out-of-state student because that student is still going to pay substantial tuition to go there," Hicks said.

This spells trouble for the state economy. Out-of-state students are far less likely to stay in Indiana once they complete college. Hoosier students who leave Indiana to go to college almost never return. With these two groups eliminated, the only young workforce that remains are those without a college degree.

"Indiana is essentially securing a really poor future for itself," Hicks said.

Indiana is 'down-skilling' its workforce, leading to stagnant economic growth

The next generation of workers in Indiana are primarily high school graduates who may have a technical certificate from a trade school.

"It is really a function of down-skilling Indiana's labor force both by cutting money to higher education and telling students that they don't need to pursue post-secondary education as a goal for employment growth and lifetime income stability," Hicks said.

A non-college educated workforce reduces the likelihood businesses will relocate or expand into Indiana.

"Look, Purdue is arguably the best public sector technology university in the world — if it's not No. 1, it's got to be the top two or three. IU is the No. 1 medical degree-granting public university in the Western Hemisphere. We have great schools, but if we're not going to do things to get Hoosier kids to go to them and to stay here, (businesses) are just going to go to where the workers are," Hicks said.

Hicks uses the example of Intel, a multinational corporation and technology company, which recently expanded into Ohio rather than Indiana.

"They went to a higher tax-rate state in Columbus, Ohio, because they wanted to have access to the workers," Hicks said.

For the past 30 years, 80% of net job growth in the U.S. has gone to college graduates, according to Hicks. High school graduates rely on replacement jobs — positions that open only when another worker retires.

"High school-educated workers with a two-year degree, they have plenty of places in the economy, but we're only growing more jobs in amongst people who've been to college," Hicks said.

The jobs high school-educated workers are securing are also expected to become more automated in the next few decades. Currently, state Legislators are expected to consider a new, more individualized approach to funding higher education that is based on school-specific goals rather than its blanket formula. But this slow-moving process won't counteract the effect of the higher education cliff.

“The past decade is going to have implications on the state's economy for decades. Even if we reverse this next year or the year after, we’re still going to have a much worse 2030, 2040 and 2050 than we would have had otherwise if we had sustained our push for better education, for educational attainment," Hicks said.

Hicks bucked the argument that investment in trade schools and technical jobs is the future for Indiana.

"The idea that we have foisted upon young Hoosiers for everything, from our career paths to speeches by presidents of community colleges, really caused students to stay away from school and the prices have gone up," Hicks said. "This will cause substantial long-term damage. It's already started."

Reach Rachel Smith at rksmith@heraldt.com.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Indiana policies accelerated its higher education enrollment drop off