Impeachment managers: What do they do, and whom will Nancy Pelosi pick?

WASHINGTON — With the House of Representatives expected to vote affirmatively on two articles of impeachment against President Trump, Speaker Nancy Pelosi now faces the task of choosing “impeachment managers” from the chamber’s ranks.

The role of the impeachment managers will prove critical to Democrats’ prospects as they attempt to remove Trump from office for, according to their allegations, trying to exert political pressure on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. The Democrats charge that Trump also tried to obstruct their investigation into that pressure campaign, which lasted throughout the spring and summer of 2019.

An impeachment manager is “the impeachment analog of a prosecutor,” said University of Missouri School of Law professor Frank O. Bowman III, who is the author of “High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump.” The impeachment manager, according to Bowman, “presents the case on behalf of the lower house to the upper house.”

According to an explanation of the impeachment process by the Congressional Research Service, “The House managers, who might be assisted by outside counsel, present evidence against the accused and could be expected to respond to the defense presented by the accused (or his or her counsel) or to questions submitted in writing by Senators.”

An impeachment manager should be “someone with experience building a case factually,” according to Kim Wehle, author of “How to Read the Constitution — and Why.” As a young attorney, Wehle worked with Kenneth Starr on what eventually became the Bill Clinton impeachment inquiry. “You would need a trial lawyer,” Wehle says. Someone who can show “how the story unfolds” instead of merely reciting a litany of facts.

Impeachment is described in Article 2, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution, but the specific duties of the impeachment manager are themselves ill defined. Bowman of Missouri Law says the office dates back to 1376, when what came to be regarded as the Good Parliament impeached Lord Latimer, a corrupt official at the court of Edward III. The case is widely believed to have been the first impeachment undertaken in Western society.

The case against Trump has been laid out in reports from the House Intelligence Committee and the House Judiciary Committee, as well as the articles of impeachment themselves. Republicans have depicted those reports as selective and partisan, with GOP members of the House Intelligence Committee writing a report of their own.

In the Senate, the impeachment inquiry becomes a trial, with the managers as prosecutors and the chief justice of the United States presiding over the process. If two-thirds of the chamber’s 100 members vote to convict Trump, he will be removed from office. The Senate is now narrowly controlled by the Republicans, with 53 seats held by members of the GOP. And while none of them has indicated that he or she will vote to convict Trump, a few — including Mitt Romney of Utah and Lisa Murkowksi of Alaska — appear to at least be open to persuasion.

That will make the task of the managers all the more important. With the nation watching the first Senate trial of a sitting president in two decades, the managers will become the impeachment inquiry’s public face.

During the impeachment of Bill Clinton — who in 1998 faced four articles related to perjury and obstruction of justice in the investigation into his relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky — House Speaker Newt Gingrich selected 13 impeachment managers.

One of these managers was James Rogan, a congressman from Los Angeles. In his book on the Clinton impeachment, “Catching Our Flag,” Rogan describes how he was courted to be a manager by Gingrich, who liked his reputation as a law-and-order prosecutor and judge.

At one point before his selection as a manager, Rogan flatly informed Gingrich that the speaker “ran a grave risk of appearing to be on an opportunistic witch-hunt” if he was personally involved in the process. The confrontation seemed to impress Gingrich, if anything, and sometime later Rogan learned that House Judiciary Committee Chairman Henry Hyde, R-Ill., had selected him as one of the managers.

Rogan vowed to use the same briefcase during the impeachment trial that he had used during this prosecution of gang members in Los Angeles decades before. Nicknamed the Brown Beast and subject to much press attention, the briefcase attained a modicum of celebrity and was eventually acquired by the Smithsonian Institution.

The impeachment inquiry is the rare occasion when the House gets to make its case to the smaller and more august Senate. The occasion is even more striking when that case is made in a divided Congress. Back in 1998 with Clinton, it was a Republican House making the case to a Republican Senate. Today, House Democrats will be making their case to a Republican Senate, most of whose members are reluctant to convict Trump. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has proclaimed he is in “total coordination” with the White House.

Even so, Rep. Steve Chabot, R-Ohio, remembers Hyde preparing him and the other managers for their turn before the Senate. “I don’t think we’re gonna be welcome over there,” he paraphrases Hyde as saying. Chabot says he recognized that serving as one of the faces of the most high-profile part of the impeachment process was risky, especially since many Americans disapproved of Republicans’ focus on Clinton’s private life.

“I didn’t get elected to this job to duck the tough calls,” Chabot says.

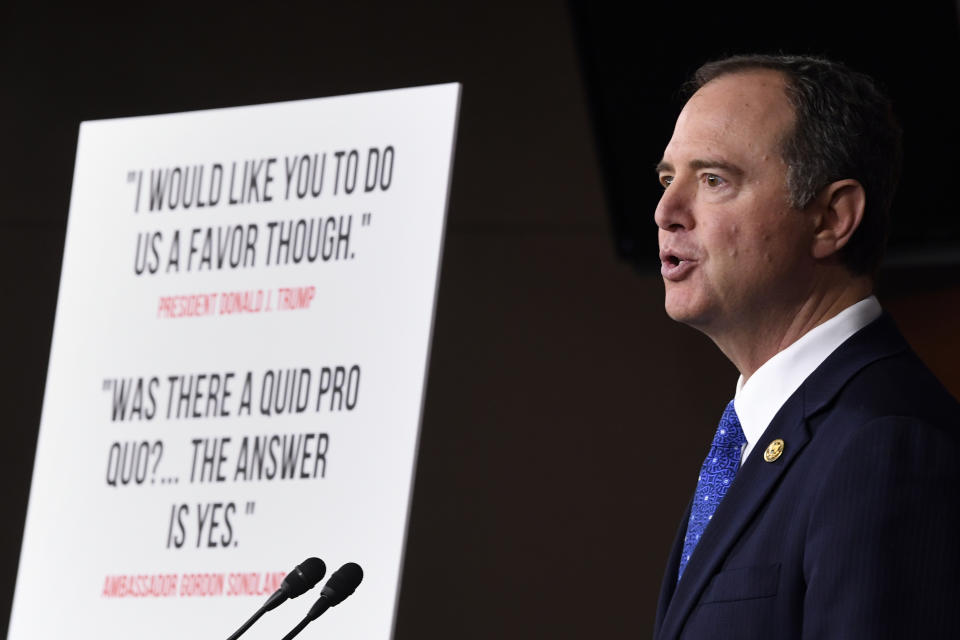

Impeachment didn’t end up ending Chabot’s career in the House, but Rogan was not so lucky. In 2000, he was narrowly defeated by an ambitious young former prosecutor named Adam Schiff. Twenty years later, Schiff is a leader in the impeachment inquiry into Trump, and as the head of the House Intelligence Committee, he is widely expected to be named as one of the impeachment managers.

Schiff also previously acted as an impeachment manager in the case of Thomas Porteous, a federal judge in Louisiana who was accused of abusing his power for personal gain. “It’s really useful to have those prosecutorial skills,” says Bowman, the impeachment expert from the University of Missouri.

Wehle, the former Starr assistant counsel, thinks that for all his fluency with the facts of the case against Trump, Schiff is not best equipped to sell that case to skeptical Republicans, not to mention a wary American public. “A good trial lawyer is someone who is relatable to people,” Wehle says. “It wouldn’t be Adam Schiff.”

In Wehle’s view, Democrats badly need to avoid the kind of hearing that took place before the House Judiciary Committee earlier in December, when three top constitutional scholars testified on the Trump impeachment. The hearing was derided by some as overly academic, and opened Democrats to charges that impeachment was elites venting their ire at Trump.

Schiff is only one of several names being bandied about on Capitol Hill. Another potential manager is Rep. Jerry Nadler, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. Typically, the managers come from either the Judiciary or Intelligence committees. “Those guys know the case,” Bowman says.

However, nothing stipulates that Pelosi must choose from those two committees. The House Oversight Committee was also involved in the Trump impeachment inquiry, as was the House Foreign Affairs Committee. The House Financial Services Committee and the Ways and Means Committee also had roles, albeit less public ones.

A spokeswoman for Pelosi declined to speak on the record about the selection of impeachment managers. But the speaker’s closely held deliberations have only heightened speculation in Washington.

A likely candidate along with Schiff and Nadler is Rep. Zoe Lofgren of California, who was a staffer on the House Judiciary Committee during the impeachment proceedings against Richard Nixon and a member of the same committee during the Clinton impeachment. “In the past few weeks, I’ve received many questions about how this impeachment process compares with the two I experienced before,” Lofgren recently wrote in Newsweek. “Answer: Unfortunately, this case is far worse.”

The position of impeachment manager could also boost a rising star within the party. Accordingly, some believe that a potential manager could be Rep. Val Demings of Florida, who once served as the chief of the Orlando Police Department. During the impeachment hearings, Demings provided one of the more rousing moments, deftly pivoting from the inquiry itself to her own personal history during a House Judiciary hearing that mostly had both parties repeating what they had been saying for weeks.

“America has been through tough times before,” Demings said, “and I am sure that we will go through tough times again. So I do not fear this moment — or this time.”

She then described being raised in poverty, along with six siblings, by working-class parents.

“I believe that only in America can a little black girl, the daughter of a maid and a janitor, growing up in the South in the ’60s, have such an amazing opportunity” to serve in the U.S. Congress. “I come before you tonight as an American dream realized.”

She also alluded to “America’s complicated history” and her own enslaved ancestors before alighting on a point that seemed to have nothing and everything to do with Trump: “My faith is in the U.S. Constitution.” While this was a departure from the usual impeachment fare, Americans hardly punished Demings. A video clip of that statement became a Twitter sensation and has been viewed 600,000 times.

A spokesman for Demings declined to comment.

Rep. Hakeem Jeffries of New York is also likely to be asked by the speaker to serve as an impeachment manager. Jeffries has regularly given media interviews discussing the ongoing impeachment process.

He is also a former litigator who could be deployed for cross-examinations. In prior hearings, he showed himself as a tenacious questioner in exchanges with hostile witnesses, including acting Attorney General Matt Whitaker and Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski.

Rep. Eric Swalwell of California, a former presidential candidate and a relentless critic of Trump, is another potential impeachment manager. An aide to a House Democrat called Demings and Swalwell “two of our most effective messengers in the hearings.”

“I’m focused on the busy week ahead of us, including our floor vote on the articles of impeachment,” Swalwell said in a written statement to Yahoo News.

Rep. David Cicilline of Rhode Island also raised his stature during the hearings. A former public defender, he seems to have grasped that Democrats risk losing people’s attention with complex arguments about foreign aid and constitutional precedents.

During a recent hearing, Cicilline worried that “most folks are probably sitting at home thinking: What in the world has any of this got to do with me? How does stopping foreign aid to Ukraine actually affect my life?”

Other names include Rep. Pramila Jayapal, the progressive from Washington state, and Rep. Jamie Raskin of Maryland, who has a law degree from Harvard and has taught law at American University. Some first-term Democrats even want Rep. Justin Amash, who defected from the Republican Party earlier this year, to be appointed an impeachment manager, as that would presumably give the proceedings a less partisan feel.

The full House will vote on impeachment on Wednesday. Pelosi is expected to announce her roster of impeachment managers shortly after that vote.

Asked about advice he would offer to those managers, Chabot joked that he’d “probably tell ’em to mess it up,” since, like most Republicans, he believes nothing Trump did rose to the level of an impeachable offense. Growing more serious, he offered counsel that no parent would dispute: “Do your homework.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: