'A huge lift': Biden's bet on child care is closer to reality but could it boost expenses for some?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

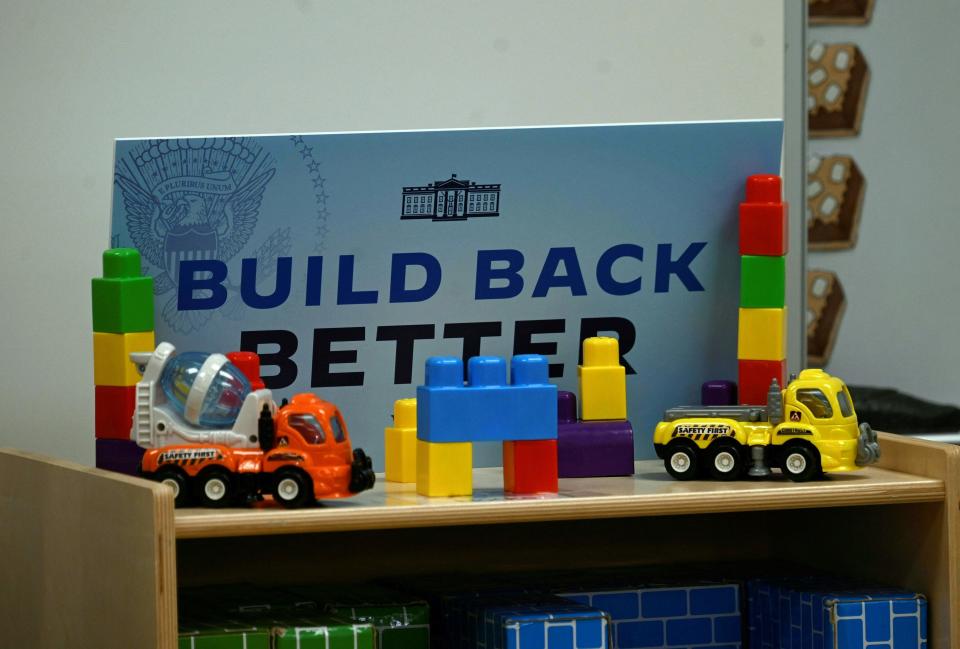

WASHINGTON – Making child care more affordable is one of the consistently popular components of President Joe Biden’s ambitious domestic agenda.

The child care plan included in the wide-ranging domestic spending package passed by the House this month would boost wages and employment for child care workers in the short term and raise earnings for parents – particularly women – in the long run, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office said last week.

But even some supporters of the expensive initiative have questioned whether there could be adverse effects because of the way the plan is structured. Child care costs could go up for families who make too much to qualify for help and no parents may be helped in states that opt out. States and the federal government also face a tight timeline to get the program off the ground and uncertainty about whether Congress will continue the funding after 2027.

"I don't think it's destined to fail," said Marc Goldwein, senior policy director for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. "But I think it's going to be a huge lift to make this work properly and I'm very worried that in many parts of the country, it's not going to work, or it's not going to work well."

Navigating the child care system in the U.S. is bleak. Child care assistance is out of reach for millions of working parents, who are either forced to leave the workforce to stay home because of exorbitant costs or rely on family and friends to help out, according to Rasheed Malik, associate director of research for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.

"There's all kinds of different ways that people stitch together their lives to deal with this really extreme structural, systemic failure," he said.

Families with infants are paying nearly $16,000 a year on average on center-based child care, according to the Center for American Progress, or 21% of the U.S. average income for a family of three.

Biden's child care plan is expected to be a major talking point for Democrats looking to retain their razor thin majorities in Congress in next year's midterm election and the spending bill may be one of the last chances to achieve the longstanding Democratic priority. But the party may be rushing to push through a policy that might not be ready, Goldwein said.

"I don't think they've gotten the design right yet," he said. "I think we're better off taking the bites that we know are going to work and spending more time thinking through how to how to get this right."

But advocates argue the bill is a chance to transform what the Treasury Department has called an "unworkable" system that hinders a parent's ability to contribute to the U.S. economy.

The earnings of parents who receive subsidized child care would likely rise, according to the CBO, because they would get more work experience, which leads to greater employment and higher wages. Those effects would probably be stronger for women, CBO concluded, because they're more likely to leave the labor force to care for children.

"Having access to low-cost or free child care would allow them to work more," CBO said.

Eligibility and messaging

The House bill is designed to dramatically reduce child care costs for parents by capping the expense up to 7% of their annual income through subsidies. Only families earning below their state's median income will be eligible for assistance in the first year. In the second year, eligibility is extended to those making 125% of the state's median income, 150% in the third year and 250% in the third year.

Funding to help states expand child care centers and open new ones will be administered based on the Child Care and Development Block Grant, which every state participates in, during the first three years. States would be required to use half of allotted funds to expand access to child care subsidies, 25% for child care supply, quality building activities and 25% of funds on either subsidy and grant expansion or supply and quality building and up to 7% on administrative costs. By the third year, the program transitions to an entitlement program, where the federal government covers all costs related to child care.

One of the biggest critics of the way the plan is structured is Matt Bruenig, president of the People’s Policy Project, who has been pushing for changes for months.

Bruenig said the subsidy cliff has since been adjusted so fewer people would be affected.

“We just bumped it up higher in the income ladder, which is a definitely a plus,” he said. “But the problem is still there.”

Bruenig argues the only cutoff should be the plan’s limit that parents shouldn’t pay more than 7% of their income on child care.

“You don't need a hard cutoff, because at some point, you make a high enough income, that 7% of your income is simply equal to the cost of childcare,” he said. “So, it should naturally taper off.”

The phased-in eligibility also could cause confusion among families on whether they're able to apply, Goldwein said.

"There's going to be a ton of confusion over who's eligible and who's not eligible and for how much and I think that's going to, among other things, potentially undermine the popularity of the subsidy," he said, noting that Democrats are hoping the policy would prove to be popular enough that it would be renewed by a future Congress.

While supporters contend the communication effort around the program is critical, they point to the popularity of the COVID-19 relief funds that were doled out to states to help keep child care centers afloat or bring back employees made jobless by the pandemic. Those relief dollars will help states transition into the new program, advocates say.

"There's a whole level of outreach that needs to happen," Malik said. "With the (American Relief Plan) dollars that went out from for child care, we've seen governors of all political stripes making announcements and holding ceremonies and being proud of their ability to pass along federal money, but with a state name and face on it. And I think they'll have the opportunity to do the same thing here."

More: The child care industry collapsed during COVID-19, so Biden’s giving it $39B from the stimulus

New demand and supply shortages

The child care policy is structured so low-income families would receive the largest subsidies first in order to target the families most in need.

More than 50% of Americans live in child care deserts or areas with an insufficient supply of licensed child care, according the Center for American Progress. During the pandemic, some 20,000 providers shuttered.

But providing a flurry of subsidies to families who were not using a licensed child care provider would likely create a surge in demand – and with the industry already struggling with a labor shortage, that could ultimately drive up prices for middle-class families not yet eligible for subsidies.

"There's a lot of potential landmines in this particular design and it's not just one thing that's an easy fix," Goldwein said of supply concerns.

To confront this issue, the bill also invests in raising wages for early childhood educators in order to attract new workers after the pandemic depleted the sector's workforce. The average wage for a child care worker in 2020 was $12.24 per hour, or $25,460 a year, according to the Labor Department, placing them among some of the lowest paid workers.

Malik and others advocates said states are already using the COVID relief funds released earlier this year to recruit new staff, but a surge in demand for care could force wages up even more as employers look to compete with fast-food restaurants or big box stores that offer paid time off or health benefits.

While the government is covering more of the cost, parents above the income eligibility threshold are still paying higher prices for the same care they're receiving.

"There's an anticipation that this is going to be a kind of a balancing act of expanding supply, increasing wages and extending more subsidies out to kids," Malik said.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-WA., argued the bill shifted the cost of care from working families to the highest income brackets in the country, who will face higher taxes under the House bill.

“The status quo of rising child care costs and waiting lists is not working for parents, which is why this bill lowers more and more families’ child care costs over the first three years, while prioritizing helping states invest in opening new providers, raising wages in the early childhood workforce, and adding slots," said Murray, a former pre-school teacher and one of the plan's architects.

By the time the program is enacted, she added, nine in 10 working families will be able to find and afford quality child care in their neighborhood, "paid for by raising taxes on the very, very wealthiest in our country.”

More: Finding day care was already a 'confusing and frustrating maze.' Coronavirus made it worse.

State participation

One of the biggest concerns with the policy is whether states will adopt the plan and what happens to those who are left out of the federal push.

If the federal legislation becomes law, states will have to pass their own bills to accept the federal funds, cover their portion of the cost and implement the plans.

Some states may not want to spend their own money or may be wary of starting a new program when the federal funding would only be authorized through 2027 unless a future Congress extends it.

GOP-led states may also have ideological reasons for not participating in a Democratic plan.

More than a decade after passage of the Affordable Care Act, a dozen states have not expanded Medicaid eligibility despite significant financial incentives.

Noting that Democrats control both the legislature and the executive branch in just 14 states, Bruenig said the federal government should step in if a state doesn’t act.

To make up for the loss of a state’s share of the cost without penalizing states that kick in what they owe, subsidies wouldn’t be as high in states with federally-run programs. Bruenig said that would create political pressure for states to act.

“Nobody knows the future of course, but it seems utterly delusional to not see state non-participation as a massive threat,” he recently wrote.

But the bill includes a work-around for municipalities, school districts or other localities which can apply directly to the federal government to access $40 billion in funding for child care and pre-kindergarten if their state chooses not to participate.

Matt Lyons, director of policy and research for the American Public Human Services Association, said expanding child care access and affordability will be a “heavy lift,” despite the obvious benefits.

The full implementation period will be needed to restructure and expand the child care market, he said.

“And states that opt in will have to push forward with uncertainty of long term funding and sustainability of the program,” said Lyons, whose group represents state and local health and human service agencies.

Lyons said it will be challenging for states to make the necessary investments in staffing and technology when there’s no assurance that federal funding will continue after 2027.

Prospective child care providers will also want to know what happens if the money goes away after they’ve raised wages and quality standards.

“The private market already gets by on razor thin margins and will not be able to sustain these costs on their own,” he said.

But the bill's supporters are confident states will get on board. Working moms and children are not as stigmatized as health care was under the Affordable Care Act, Malik said, and it's an issue that governors have heard about repeatedly from their voters who endured child care problems during the pandemic.

"Getting that news out to families in their state is going to be an opportunity honestly for governors of all stripes to tout what great things they've done to expand childcare access in their state," Malik said.

"If the state decides to not do it, then you know, the people there lose out but they lose out on the chance to take credit for solving a problem."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Child care: Biden plan to cut costs could actually boost expenses