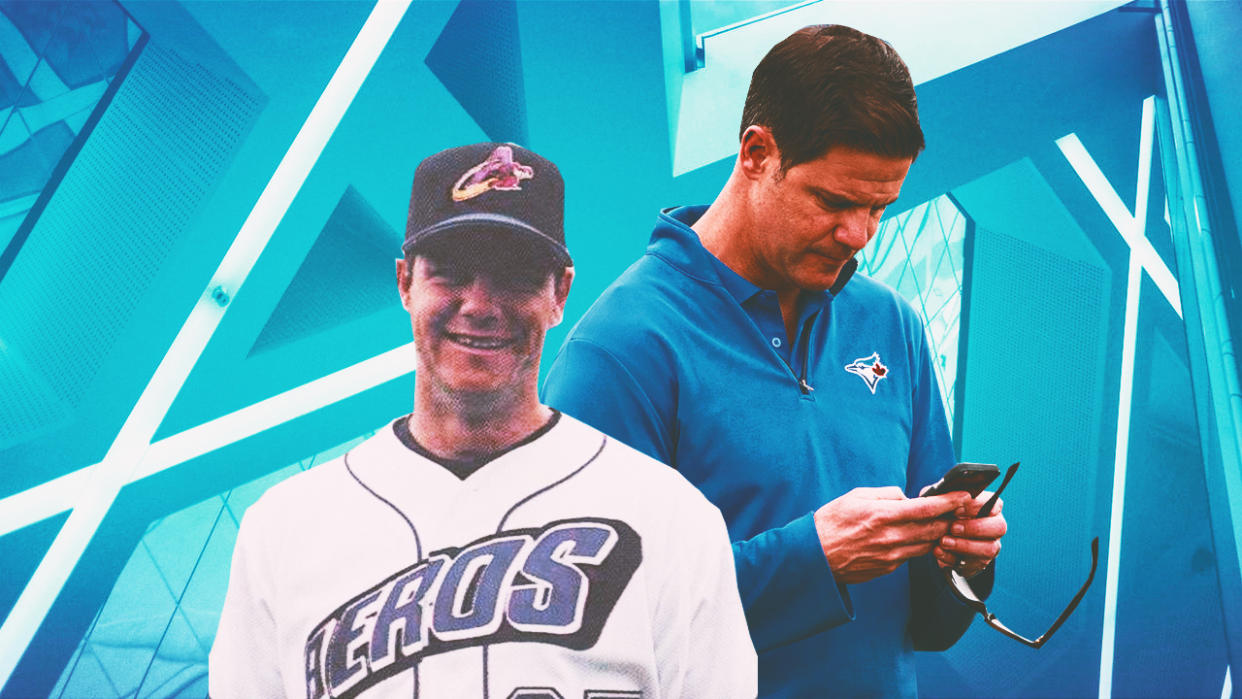

How life as a minor-league grinder explains the Ross Atkins we see today

At first glance, Ross Atkins is a difficult man to imagine in his 20s.

The Toronto Blue Jays general manager has a fairly defined public persona that centres around characteristics like being even-keeled, taking the long view, and avoiding risks — not traits we generally associate with a young man, or ones that accurately describe a younger Atkins.

It’s easy to forget that before the 46-year-old was an executive he was a pitcher, a longshot drafted out of Wake Forest by the Cleveland Indians in the 38th round in 1995. Back then, he projected a persona as well, albeit one that’s the polar opposite of what we see today.

“As a college performer I felt as though I had to be that fiery, extremely aggressive guy to get everything out of my physical ability,” Atkins says. “Right or wrong I didn’t feel like I was as physically gifted as my competition. That continued for a while in the minor leagues.”

The story of Atkins’ trip through the minors is not the most direct explanation for who he is now, but it might be the best. It was during his five-year career on the mound that his maturation “really started to take shape and crystallize” and he began to “feel like a man.”

That process began in Watertown, New York, a town with a population that’s hovered just south of 30,000 for the last 40 years. Atkins and his fellow Watertown Indians lived in a small complex which then-teammate Scott Winchester, who wound up carving out an MLB career with the Cincinnati Reds, now refers to as a “bunker.” Atkins roomed with Marc Deschenes, a 20th-round pick from University of Massachusetts Lowell, and lived what he describes as a “very, very simple existence.”

“Our days were waking up, eating something the Deschenes family had filled our freezer or refrigerator with, stopping by Subway and heading to the field,” Atkins says. “After games, walking to the one bar in town having a couple of beers and doing it again.”

Living a pared-down lifestyle helped Atkins narrow his focus to a few things that would ultimately be crucial to his path decades later. Early on, he showed the ability to bring the Latin American and American players together due to his command of Spanish and his background growing up in Miami.

“My high school team was probably 60-80 percent Latin American, mainly Cuban American. So I was accustomed to playing with these guys,” he says. “Eli Marrero, when he first got to my high school he didn’t speak English. So that was not as foreign to me as it might have been to someone who was from Oklahoma.”

“They felt they could lean on Ross,” Deschenes recalls. “Whether it was help with cooking or essential items and day-to-day type stuff.”

Eight years after touching down in Watertown, Atkins wound up as the Indians’ director of Latin American operations. Although for that to happen, he also needed to bring his focus to baseball. With an economics degree in hand, it wasn’t always clear to him the sport would be the focal point of his career.

“I wish I could say I had the ‘I’m going to do this and make the major leagues’ attitude,” he says. “I didn’t start to feel that until I got into the Cleveland system. Initially it was, ‘I’m going to do this and see how far it goes.’”

Being around players like Winchester and current Blue Jays first base coach Mark Budzinski, who had tunnel vision about achieving their MLB dreams, Atkins became more and more focused on his own. Ironically, the guys who were more dialled in on the baseball side admired his ability to not sink all of himself into the game.

“To be able to have ways to get away in the morning, and in the late evening after the game is huge,” Budzinski says. “Ross did excel at that. He could separate the two a lot better than some us at that age could. I speak for myself when I say I was horrible at it initially.”

The early observations made about Atkins weren’t always so profound. One thing that jumped out to almost all of his teammates, for instance, was his wardrobe.

“I think it was only J. Crew and Banana Republic,” Deschenes says. “He kind of got me into that style a little bit. He’d be like ‘you gotta get rid of these jean shorts. Let me take you to J. Crew and up your style a little bit.’ I’ll never forget that about Ross.”

“There wasn’t a lot of call for khakis or button downs, we were more wearing sweat shorts and t-shirts,” Winchester adds. “He was a Miami guy so it makes sense that he was ahead of the curve.”

Even working with Atkins more than 20 years later, Budzinski still experiences ribbing on his sartorial decision-making.

“He does it to me all the time,” he says with a chuckle. “He still reacts to my shirts and says ‘come on, let’s step it up a bit here’ whether it’s the material or the fit.”

On the field, Atkins got off to an inauspicious start. His first outing was an unmitigated disaster. When manager Joe Skinner finally took the ball from his hand he had an ERA of infinity, thanks to his inability to record an out. Things markedly improved from there, though, and Atkins finished the season with a 3.26 ERA.

When you ask for scouting reports of the right-hander, a lot of the same words come up, like “competitor” and “grinder.” You also get descriptions of a guy who would stick around and keep his team in the game even if he got hit early, despite how his first start turned out. Atkins’ self-evaluation, at least with the benefit of hindsight, is pretty matter-of-fact.

“Max effort. Everything I’d got. Some deception, but relied heavily on my changeup which was a deceptive pitch off a max-effort fastball,” he says. “I always struggled to find a breaking ball that was consistent. When I had a good breaking ball I was very effective. When I didn’t, I wasn’t.”

Atkins’ next stop was Columbus, Georgia, in 1996, a significantly bigger town of close to 200,000 just outside Atlanta.

He had the same manager in Skinner, who moved in lockstep with Atkins through his entire professional career, coaching him at four different levels over five seasons. Their bond grew progressively stronger as their journey ran in parallel. Atkins credited Skinner for helping him with his composure as a competitor, while Skinner got close enough to the pitcher that he began to use him as a sounding board.

“Maybe it would be Memorial Day weekend, or maybe it would be the All-Star break, or whatever it was. I would get the players together and give a little talk about life,” Skinner, who’s now managing the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings, recalls. “After doing that for a few years Ross had listened to every one of them. So I’d pull him aside and ask him how I did.”

One of those speeches in particular always stuck with Atkins more than 20 years later.

“There was one talk where he said to a group of guys, ‘I hear everyone talking about this has to be my year, because it’s Rule 5 or roster protection. Guys, there is no year that’s important. Every year is important. Every year is the same. Why increase the pressure on it?’” he says. “I remember that really resonating with me.”

Another crucial development in 1996 was the introduction of Marco Scutaro into the fold. Scutaro sat beside Atkins on long bus rides and they taught each other Spanish and English respectively. The Venezuelan had never been outside his country before and didn’t know what to expect from life in the United States.

“I didn’t know anything,” he says. “I was like a baby for him.”

Even the most mundane outings were understandably daunting for Scutaro, who still remembers the dread a simple trip to Subway entailed.

“When I tried it I thought ‘wow this is delicious’ and then my next thought was ‘how the hell am I going to order this.’” he says. “They ask you so many questions. I thought ‘I have no chance without Ross.’”

As Atkins was unknowingly setting the groundwork for his future career, he was also improving on the field. The then 22-year-old led the Columbus Red Stixx in innings pitched and posted a 3.93 ERA as they reached the South Atlantic League semifinals.

“I remember that being the first year I was thinking, ‘Wow I’m so much better than I was a year ago if I continue on this I’m going to be a major leaguer.’”

In 1997 he continued to feel on the right track. Atkins was getting stronger, his velocity was ticking up and he felt like he was “getting on some radars.” Now he was at High-A Kinston, although he didn’t spend too much time in the town itself.

Atkins convinced a few teammates, including Danny Peoples, the team’s first-round pick in 1996, to come out with him to Greensville, North Carolina, a town about a 45 minute drive away from the ballpark that was home to the University of East Carolina.

“He nudged us to consider moving out that way as opposed to staying in Kinston. We’d just come from college and wanted a college atmosphere,” Peoples says. “There were more shops and restaurants and a little bit of nightlife to explore.”

Peoples remembers Atkins as both a guy always on the lookout for novel experiences and adventures who encouraged others to do the same. When it came to his qualities as a roommate, though, cleanliness was by far and away his greatest asset.

“He always had the most neatly folded t-shirts in the house,” he says with a laugh. “One of the things that I truly admired about Ross is if you had a load of laundry in the dryer and he went down to do his, when you went back down there to ditch your load he would have taken your load out and folded it for you.”

Although Atkins pitched to a 3.62 ERA that season, objectively the cracks began to show. His walk rate ballooned to 4.8 BB/9 and he was pulled from his team’s rotation as they made their playoff push.

“When you’re with somebody for a long time you have to have tough conversations. I remember pulling him in 1997 when we made the playoffs,” Skinner recalls. “For the team it worked out because he was more valuable out of the bullpen. But obviously I had to take him out of the rotation. He wasn’t happy about that.”

The next season is when things really started to take a turn. A promotion to Double-A Akron resulted in a rising ERA (4.19) and plummeting strikeout rate (4.4 K/9), even as Atkins worked almost exclusively in relief.

“I came out of the rotation pretty early in the season,” he says. “I fared pretty well out of the bullpen, but I had an average year for a 24-year-old in Double-A. That’s where I realized I had to do something exceptional. I kept trying to do something exceptional.”

While Atkins struggled on the mound, life off the field was good. He lived in a small house with Peoples, Budzinski, and Darren Stumberger — a slugging first baseman with a canary yellow Mustang who he’d been teammates with since 1996.

The house had a couple of trademark features including a cemetery just past the backyard and a ping pong table in the garage that — much like virtually every ping pong table in human history — doubled as a beer pong table.

Atkins is much more explicit about his exploits at the former.

“I’m pretty sure I could beat everyone we lived with at ping pong,” he says. “Beer pong, I don’t remember who was good at it and who was bad at it.”

Some of his teammates have better recollections of what Ross brought to the table — literally.

“I would give him a seven out of 10,” Budzinski says. “He’s not hurting your team. He’s definitely going to compete, but he’s not the most talented.”

Deschenes is a little less generous.

“Started out as a seven,” he says. “As the game went on declined to maybe a five.”

Whatever type of pong was going on, a common thread was the kind of music being played.

“If we were in the garage, we had a Dave Matthews CD on,” Peoples says.

Regardless of who you ask about this time, it’s clear Dave Matthews was a constant.

Even Scutaro, who had no prior knowledge of American music, recalls the preponderance of Dave Matthews who was played “ad naseum,” according to Deschenes.

“Dave Matthews Band. I still remember,” Scutaro says. “I had no clue back in those days. But that was one of their bands for sure.”

“When I hear that music I think of those guys,” Atkins says with a smile.

While Atkins appeared to be living an idyllic minor-league life in Akron, the consternation about his baseball path was at an all-time high. Following his 1998 season, he tried to change just about everything about himself as a pitcher from his delivery, to his arm angle, to the depth on his breaking ball.

None of it worked.

Atkins repeated Double-A Akron and his performance dipped significantly. His ERA ascended to 5.77 and he walked more hitters than he struck out for the first time. It was pretty clear to him it was over.

“What I was doing, albeit fine for Double-A, isn’t enough for the major leagues. I have to try something different,” he says. “When I tried something different and didn’t get the results, I started to think ‘OK am I out of time?’”

Like so many playing careers, Atkins’ simply petered out. He could’ve fought to keep a dying flame alive, but it’s hard to argue with the choice, both in terms of its logic at the time and the result.

Twenty years after delivering his last pitch, his time in the minors seems like a mere footnote on a lengthy career as a baseball executive. Atkins’ years working in the Indians front office didn’t just follow his years as a player, they were the result of them — whether that was in terms of the knowledge of the game he gained, how he became aware of the plight of Latin American players, or just his development as a man.

“There’s not much like minor league baseball,” he says. “It’s an incredible maturation. If you do it for several years the commitment, the rigour, the relationships, how much time you spend with people... what’s similar to that?”

Atkins’ years as a player weren’t just crucial to his professional career, either. Perhaps more importantly to the 46-year-old, they brought him immense joy.

“Outside of my personal life, my family, wife and children, by far my fondest memories in life are playing minor league baseball.”

More Blue Jays coverage from Yahoo Sports