History of the Opera House: Avery Hopwood and the days of limelight and jazz

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

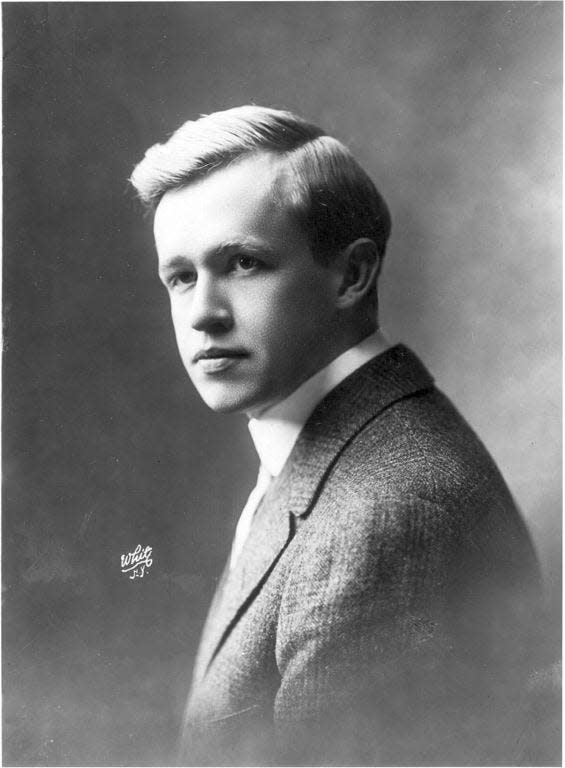

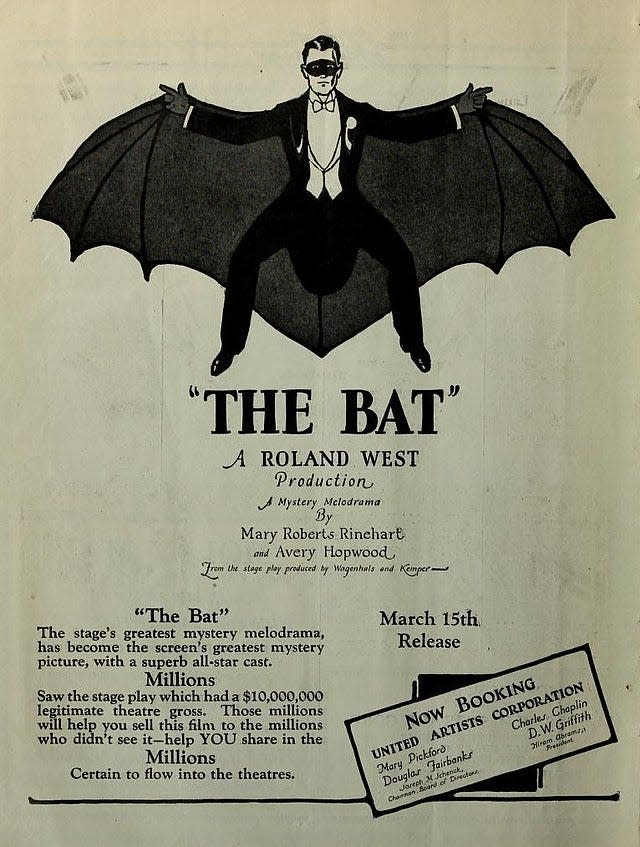

In 1919, University of Michigan graduate Avery Hopwood’s Broadway hit “The Golddiggers” heralded the arrival of the Jazz Age. Hopwood was the brightest star on Broadway, with four plays running simultaneously in 1920. His play, “The Bat,” co-written with author Mary Roberts Rinehart, became a smash hit.

“The Bat” ran for over 1,100 performances in New York and London. Producers Wagenhals and Kemper sent separate companies out on the road across America, arriving at the Cheboygan Opera House in May 1922, with accolades from the local newspaper. “‘The Bat,’ which is thrilling, mysterious and at the same time screamingly funny, stands out sharp and clear above all dramatic plays offered during the past generation. At the present, ‘The Bat’ is in its second year at the Morosco Theater, New York and in addition, broke all records for popularity in Chicago. ... ‘The Bat’ has played to absolute capacity in every city in which it has appeared and there is every indication that is performance in this city will establish new records for the City Opera House.”

“The Bat,” a detective thriller, features a wealthy widow, Cornelia Van Gorder, an aging amateur sleuth who enjoys solving mysteries. When she vacations with her staff at a remote country mansion, she is faced with her own mystery in the form of a murder and a hidden treasure. The intricately woven plot twists and turns, keeping the audience on the edge of their seats. The surprise ending was a tightly guarded secret. Audiences and theater critiques who attended the show were asked not to reveal the secret. I won’t either. Because of that unique agreement with the theatergoers, new audiences could enjoy the surprise at every opening of the play without the need for a spoiler alert.

“The Bat” was revived on Broadway in 1927 and 1953. It was novelized, ghostwritten by Stephen Vincent Benet in 1926 and adapted three times for film in 1926, 1930 and 1959. “The Bat” inspired the creation of the comic book superhero Batman in 1939. The influence of Hopwood’s “The Bat” can be seen in the look and feel of the mysterious caped crusader, from his mask to his bat signal.

Hopwood’s skill in writing dialogue brought the characters to life. In 1924, Hopwood collaborated with writer David Gray to write “The Best People.” Gray credited Hopwood. “Above all is his gift for line. No one living can put things in the mouths of his characters that convulse great audiences as he can, but there is more to a successful play than this.”

Hopwood revealed his secret for success to Gray. “Last November we went to Chicago for a short engagement in which to polish the play and get it 'set.' It was here that Mr. Hopwood disclosed the vital secret of his success. As a writer of entertainments, he believes that his plays should entertain. With him, the test of the audience is the final test. Lines that failed to get a response were ruthlessly cut whether they were his or mine. Scenes that dragged were cut or rewritten until they went swiftly and smoothly. In the first 13 performances, the play was in effect again rewritten and 20 minutes of its acting length cut out. The highbrow calls it catering to the audience. Is there any other honest method of writing entertainment?”

Perhaps Hopwood’s greatest skill was his gift of collaboration. The “Playboy Playwright” was a favorite of other authors who called him in to hone their plays. Gray said, “As we worked together, I began to note not only his amazing industry and an almost infinite capacity for taking pains, but so generous an understanding of what I had tried to do that I was speechless. I saw my characters and scenes develop as if by magic into what I had dreamed but could not realize myself.”

Hopwood died in an accidental drowning on the Riviera in 1928 at the age of 46. He bequeathed most of the fortune he made on Broadway to his mother, Jule. He donated $150,000 to his alma mater, the University of Michigan to fund a writing contest with prizes. His mother contributed for a total of nearly $350,000.

The rules stated the “prizes to be known as the Avery and Jule Hopwood Prizes, [are] to be awarded annually to students in the Department of Rhetoric who perform the best creative work in dramatic writing, fiction, poetry and the essay. Students have the widest possible latitude, and the new, the unusual and the radical are especially encouraged.”

The first Hopwood Award was given in 1931. Former winners include Arthur Miller, Lawrence Kasdan, Marge Piercy and Kathryn King Johnson (yours truly).

— Kathy King Johnson is former executive director of the Cheboygan Opera House.

This article originally appeared on Cheboygan Daily Tribune: History of the Opera House: Avery Hopwood and the days of limelight and jazz