History of Haiti: From rebellious beginnings, Haiti has been beset by violence, meddling

Haiti’s history is drenched in blood.

The world’s first Black republic, which shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic, was declared free and independent on Jan. 1, 1804, after enslaved Africans successfully rose in rebellion against their French colonizers.

With French warships threatening invasion, France, in 1825, demanded a ransom of 150 million gold francs, later reduced to 90 million, to compensate white settlers and slave owners for lost profits in what was once France’s richest Caribbean colony.

The debt hobbled the nation for generations, leaving it poverty stricken. But from the onset, the second-oldest republic in the Western Hemisphere after the United States was beset by armed conflict, foreign interventions, repressive dictators, political violence, and heads of state whose personal ambitions and desire for power fanned instability and revolts.

While many once viewed Haiti, the Pearl of the Antilles, as an undeclared American colony because of its untapped resources and strategic location in the middle of the Caribbean, Haiti’s perennial political divisions and instability would doom it to never fulfilling its potential. Instead, waves of migration over generations would reshape South Florida and U.S. immigration detention policies, with a brain drain also flowing into New York, Canada, and most recently, Brazil, Chile and Mexico.

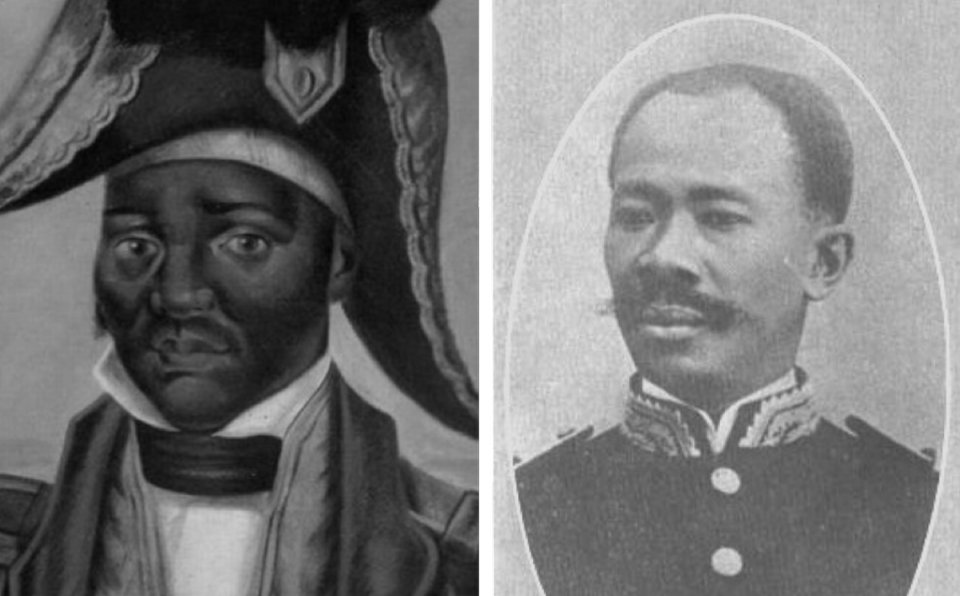

Post-independence, the country’s first leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, declared himself emperor for life. Like four subsequent leaders, he was assassinated. His body was cruelly dragged through the streets of Port-au-Prince and dismembered after an ambush that historians believe was orchestrated by his former independence allies, Alexandre Pétion and Henry Christophe. Those two would soon each rule over a divided Haiti.

The killing of President Jovenel Moïse on July 7, 2021, occurred 106 years after an enraged and grieving mob, in 1915, hacked President Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam to death after dragging him out of the French Embassy, where he’d sought refuge after ordering the slaughter of almost 200 political prisoners.

As an American warship waited offshore, Sam’s head was displayed on a pole and the rest of his body parts dragged through the streets of Port-au-Prince. The brutal killing — and President Woodrow Wilson’s concerns about Germany’s growing economic interests and influence in Haiti — led to 19 years of U.S. occupation. Under the guise of restoring order, U.S. Marines invaded to protect American assets and to forestall German encroachment.

The United States, under a treaty of 1915, took control of Haiti’s finances, including customs collection; installed its own president, Philippe Sudre Dartiguenave; and rewrote the Haitian constitution to remove a ban on foreign land ownership. As the United States sought greater control, however, it was met with fierce local resistance, especially by the Cacos, armed insurgents in the countryside who traced their origins to the fight for independence but later terrorized the population while battling the Marines.

The United States started public-works programs, using forced labor, appointed advisers and established the Gendarmerie d’Haiti. Controlled by Marines, its officers were Americans and the foot soldiers were Haitian. The gendarmerie eventually became the Forces Armées d’Haiti or FADH. After one too many coups and much interference well into the 1990s in the political life of the country, it was disbanded under U.S. pressure.

During the 1922-1930 presidency of Louis Borno, Haiti would build much-needed infrastructure: hundreds of miles of new roads, bridges and schools. A lawyer of mixed heritage, Borno worked with the Americans, who also occupied the neighboring Dominican Republic during his presidency, to develop Haiti. A year before Borno left office, Haiti and the Dominican Republic settled the border between the two.

By the time the U.S. occupation ended on Aug. 1, 1934, soon after the first visit by an American president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, structures had been put in place like the present-day, U.S.-created tax collection administration and a national public health service with a network of hospitals and rural clinics. But the birthplace of Blacks’ freedom still lacked a strong foundation for a working democracy. There was also deep resentment toward having outsiders run the country’s affairs, and a feeling that American involvement had favored the mulatto elite over the Black peasantry as the Americans in charge promoted racial segregation, press censorship and the corvée system of forced labor that was used to bolster the country’s infrastructure.

Three years after the Americans left, in 1937, thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent would be executed in a matter of days on the orders of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, most near the 224-mile border. The mass killing became known as the Parsley Massacre after the Spanish word for parsley, perejil, which was used as a litmus test to distinguish between Dominicans and Haitians. (Failure to trill the “r” in perejil meant instant death.) The episode would forever serve as a painful reminder of the animosity and division between the two neighbors.

Post-U.S. occupation Haiti ushered in modernization and the golden age of tourism, along with the International Exposition celebrating Port-au-Prince’s bicentennial. The exposition, taking place under one of the country’s more revered presidents, Dumarsais Estimé, celebrated the founding of Port-au-Prince in 1749.

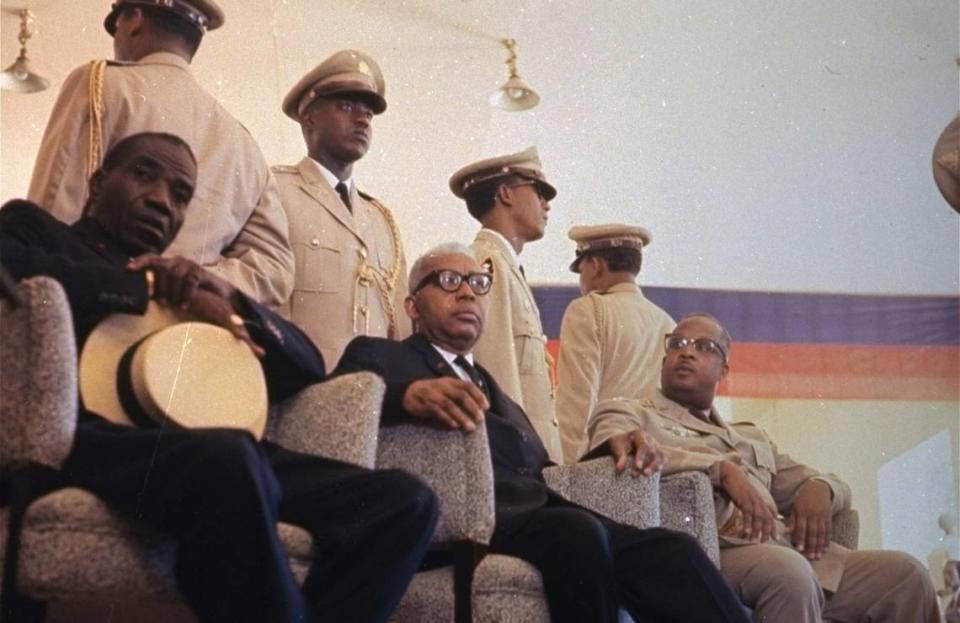

Estimé’s Black nationalism or noirisme agenda would drive Haitian politics up to the 1957 election of Francois Duvalier, who had himself made President for Life in 1964 after having his legislature replace the constitution and staging a referendum where he was the sole candidate. Under “Papa Doc” — and then his son, Jean-Claude, aka “Baby Doc” — Haitians would endure a near 29-year reign of terror.

Early in his presidency, Duvalier the father would reject communism and make any “communist activities” punishable by death. His fervor against communism, which was gaining a foothold in nearby Cuba, made the ruthless dictator and his son U.S. allies. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, thousands of middle- and upper-class opponents fled the totalitarian Haitian state, taking planes to New York, Canada, Africa and France. Then in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the urban and rural poor followed suit with the first documented boatload of Haitians washing up on South Florida’s shores in December of 1972 after others had already left for the Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos.

As they arrived in Miami, the United States labeled them “economic refugees,” a policy that continues today, detained them and returned many to Haiti, where opponents of the Duvalier regime were being silenced by the president’s paramilitary force, the Tonton Macoutes. With the brutality and U.S. support continuing, refugees would continue to flee by sea, landing in South Florida. Their presence reshaped the community while they continued to keep a keen eye on developments — and political stagnation — back home.

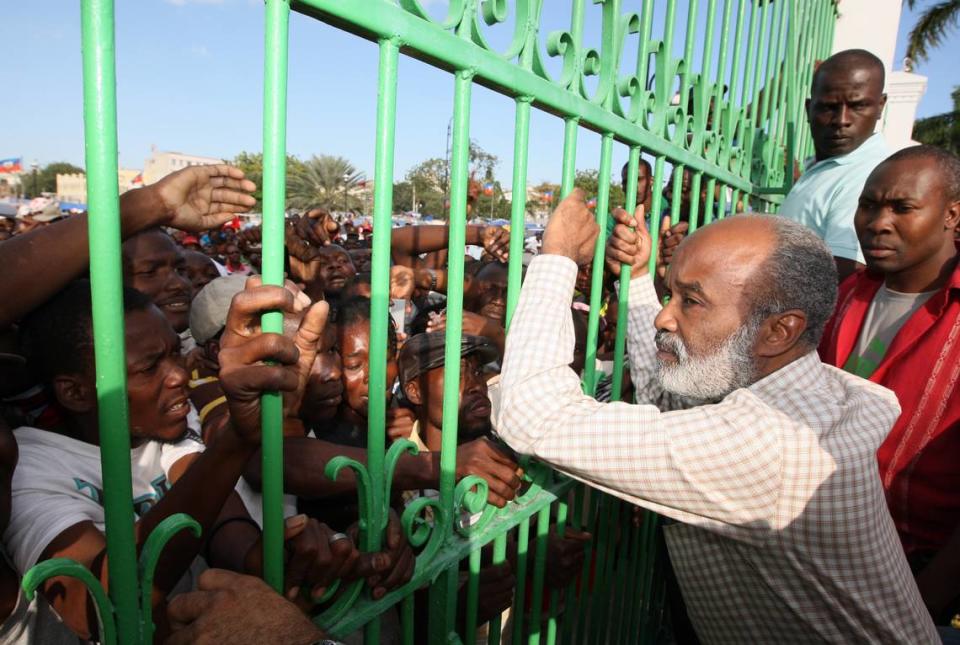

Coups, corruption, military governments, state violence, fraudulent and failed elections, migration, U.N. interventions and devastating natural disasters would mark the post-Duvalier years. The historic 1990-91 presidential election would usher in democracy with the rise of the country’s first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a former Salesian priest. But the landslide victory would be followed by his ouster at the hands of the military eight months after his swearing-in.

Aristide would be restored three years later under the protection of more than 20,000 American troops. The reaction of the population this time was a far cry from that in 1915, when Marines landed. But 10 years later, he would be tossed out once more — this time by a bloody 2004 rebellion.

Relative stability finally arrived with President René Préval under the auspices of a United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti, but it was shattered on Jan. 12, 2010, with the country’s devastating earthquake that left over 300,000 dead. A different kind of quake would come months later when amid the rubble and fallen government ministries, Préval was forced to hold general elections and later, under U.S. pressure and desire for a paradigm shift and protesters’ allegation of fraud, was made to remove his party’s presidential candidate, Jude Célestin, in favor of a popular musician with no political experience, Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly.

Today, the economy is in ruins and gang violence and kidnappings are a staple of daily life in the capital. The police force, 12,000 officers for a population of nearly 12 million, is understaffed, outgunned, and suffers from inefficiency and corruption.

Deadly natural disasters are common, including 2021’s 7.2 magnitude earthquake that killed thousands and was followed by a tropical storm. So too are man-made disasters that for two months beginning in mid-September 2022 left Haitians without fuel, food or drinking water amid a resurgence in deadly cholera as powerful gangs blocked roads, seaports and the main oil terminal.

Today, Haiti is facing some of the same issues it did a century ago — a murdered president, terrorizing bands of armed men, uncollected customs duties, a police force unable to secure the population — and another foreign intervention.

Enter Jovenel Moïse

He was branded Nèg Bannan nan, or Banana Man, part of his effort to present an image as a successful farmer, as he promised to reinvigorate Haiti’s agriculture industry, create jobs and revive the economy.

Handpicked by his predecessor Martelly, who became president in 2011, Jovenel Moïse, 53, became Haiti’s 58th president on Feb. 7, 2017 — 14 months after presidential elections that were marred by violence and allegations of fraud.

Moïse took office promising to tackle corruption but was facing a money-laundering indictment of his own on allegations he had laundered $6 million through his banana-exporting agribusiness between 2007 and 2013. After vigorously denying the allegation, Moïse later fired the head of the government’s anti-corruption unit investigating the allegations, and had the case dismissed.

Two years into office, Moïse also was accused of involvement in an embezzlement scheme dating back to before his presidency. Haitian government auditors said he had received $1.2 million worth of contracts through his business for a questionable road project. The allegedly misappropriated funds came out of Venezuela’s PetroCaribe aid program earmarked for rebuilding after Haiti’s 2010 earthquake. Past administration officials also were accused of questionable disbursements, overbilling and embezzlement of approximately $2 billion in funds, but the corruption case went nowhere.

Abroad, Moïse enjoyed the support of the United States and others in the international community. At home, besides corruption allegations, he faced a constitutional crisis, accusations that he aspired to be a dictator, mass demonstrations calling for his resignation and Peyi lòk (country lockdown), the months-long 2018 nationwide shutdown over government fuel price hikes.

Gang violence and kidnappings soared during his polarizing rule, and institutions crumbled. After dismissing most of Parliament in January 2020 with a tweet, he spent 18 months ruling by decree. He faced opposition from within his and Martelly’s Haitian Tèt Kale (PHTK) Party. Moïse’s opponents and various Haiti constitutional experts considered the final months of his rule illegitimate, insisting that his tenure actually ended on Feb. 7, 2021. They argued that Moïse’s five-year presidential term started in 2015 when the last president stepped down and the electoral process that brought Moïse to office began.

Moïse argued he still had one more year — a claim backed by the United States and the Organization of American States — because he wasn’t actually sworn in until February 2017 after the electoral process was rerun due to allegations of fraud.

During a Feb. 5, 2021, visit to Fort-Liberté in the rural northeast, Moïse, who had not long before described himself second only to God (“Après Dieu”), warned that he would not suffer the fate of more than 30 other Haitian presidents who had been overthrown or assassinated.

“After they killed Dessalines,” he said, “we have assassinated presidents; we have exiled presidents, we have imprisoned presidents. But do not forget, you have a last president who is stuck in your throats. You won’t be able to kill this one ... because I am stuck in your throats.”

Two days later, Moïse ordered the illegal arrests of nearly two dozen people, including a Haitian Supreme Court justice and a senior police officer after accusing them of trying to overthrow and kill him.

Exactly five months later, two members of the security team he credited with foiling that alleged coup and tasked with investigating the matter would be implicated in his murder.

As the United States considers another intervention force, Haitians wonder what will come next. Will Haiti repeat the past, or finally break free?