HHS shows off new 'youth care facility' for migrants — not a 'detention center'

CARRIZO SPRINGS, Texas — The otherwise abrupt turn on Munson Road in Carrizo Springs, Texas, a town of about 5,500 about 82 miles northwest of Laredo, is marked by a large billboard with an arrow pointing to “The Studios,” the former housing barracks for oil workers that was recently leased by the federal government to house unaccompanied immigrant children.

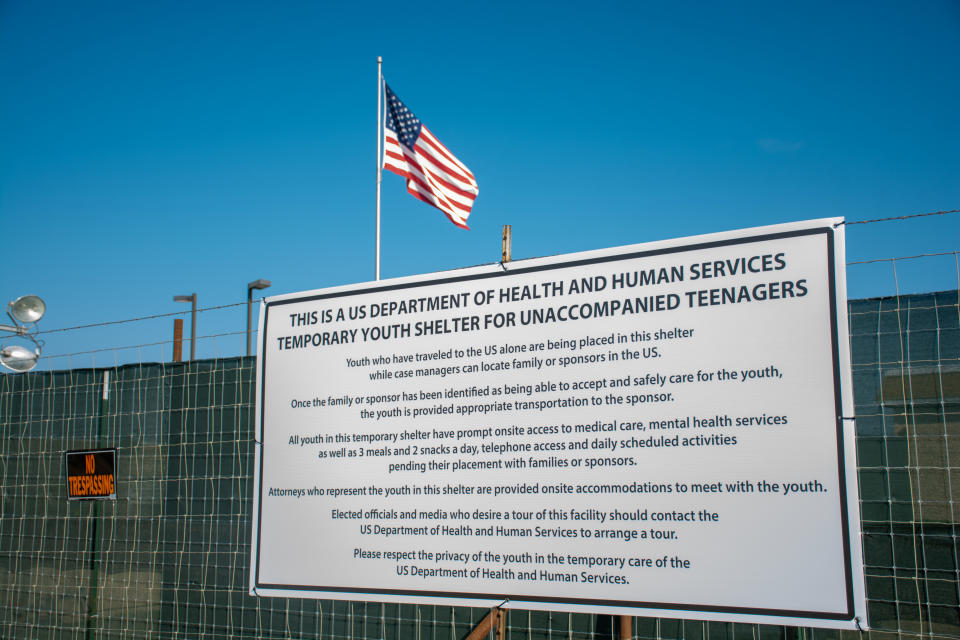

At the dead end of the single-lane road, a newer, much wordier sign hangs from wire fencing outside the entrance to The Studios.

“THIS IS A U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES TEMPORARY YOUTH SHELTER FOR UNACCOMPANIED TEENAGERS.”

Beneath that all-caps heading is a relatively detailed breakdown of who, exactly, is being housed here and why (“youth who have traveled to the U.S. alone are being placed in this shelter while case managers can locate family or sponsors in the U.S.”), the services available to residents (“medical care, mental health services as well as 3 meals and 2 snacks a day, telephone access and daily scheduled activities pending their placement with families or sponsors,” as well as “onsite accommodations” for “attorneys who represent the youth in this shelter.”

The sign goes on to direct elected officials and media who desire a tour of the facility to “contact the U.S. department of Health and Human Services,” and urges whoever may be reading to “please respect the privacy of the youth in temporary care” of HHS.

What it doesn’t say — although officials hope it’s implicit — is that this is not a detention facility run by Customs and Border Patrol, like the one Vice President Pence visited in McAllen, Texas, last week, where hundreds of men were packed into a holding pen with only a concrete floor to sleep on, and of which the reporter accompanying Pence described the smell as “horrendous.”

The posted invitation to arrange a visit — and a small media tour that included a Yahoo News reporter last week — is part of a new transparency initiative by HHS being tested at Carrizo Springs, which opened on June 30 and as of July 8 was housing 225 male and female teenagers aged 13 to 17, out of a projected capacity of at least 1,300.

Until now, entry to facilities like these — one of about 168 around the country housing around 12,500 migrant children who crossed the border unaccompanied by a custodial adult — was strictly limited to protect the privacy of the young occupants, who in some cases are fleeing gangs or traffickers. But the secrecy has led to confusion, particularly in light of the recent wave of political and public outrage over the general treatment of migrants, following reports of abuse, neglect, overcrowding, unsanitary and otherwise dangerous conditions at Border Patrol facilities.

People make things up if they can’t see inside,” HHS Spokesman Mark Weber told the handful of reporters who participated in the second of two media tours hosted at Carrizo Springs on Tuesday. The tours were the first of several the facility, which is operated by BCFS Health and Human Services' Emergency Management Division, a non-profit based in San Antonio, will hold for press and members of Congress in the coming weeks.

Days before the new influx shelter was scheduled to open at Carrizo Springs, employees of the online furniture company Wayfair announced they were planning a walkout to protest the company’s refusal to stop doing business with BCFS. The week before, more than 500 employees sent a letter to Wayfair senior management after learning that BCFS had ordered $200,000 worth of bedroom furniture, writing that "The United States government and its contractors are responsible for the detention and mistreatment of hundreds of thousands of migrants seeking asylum in our country — we want that to end." The letter added: "We also want to be sure that Wayfair has no part in enabling, supporting, or profiting from” the detention of asylum seekers by “the United States government and its contractors.”

Wayfair leadership declined to stop doing business with BCFS, explaining in a letter to employees that "this does not indicate support for the opinions or actions of the groups or individuals who purchase from us."

Weber said the employees’ protest was misplaced. “I can’t understand why people wouldn’t want kids to have beds to sleep on,” he said.

Shortly after the shelter opened, about 100 protesters gathered outside with signs saying “close the detention centers” and “abolish ICE & CBP,” according to news reports.

Weber took issue with that protest also. “I get so agitated when people call these detention centers,” he said. These are “youth care facilities.”

In fact, the federal program under which Carrizo Springs and other such facilities are run was set up to keep migrant children out of detention facilities.

Under federal law, the term “unaccompanied alien child” refers to any minor without lawful immigration status in the U.S. who does not have a parent or legal guardian in the country available to provide care and physical custody. Prior to 2002, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the predecessor to ICE) was responsible for the care and custody of UACs. But, with the passage of the Homeland Security Act, Congress transferred that responsibility to the Department of Health and Human Services, determining that the care of immigrant children in government custody should be more focused on child welfare rather than detention.

Most often, unaccompanied children are referred to HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) by the Department of Homeland Security after they’ve been apprehended by immigration officials at the border. Though there are many, particularly older boys, who cross alone or in large groups, children who cross the border with a relative, such as an aunt, uncle, grandmother or older sister who is not their parent or legal guardian are also classified as “unaccompanied” and referred to ORR as such.

Within 72 hours of apprehension, these children must be transferred into the custody of ORR, which funds a network of 168 facilities run by non-governmental organizations in 23 states. Appropriate placement is determined based on the child’s age and other particular needs, but all ORR-funded facilities provide medical and mental health services, case management, classroom education and recreation to children during the process of identifying and vetting a suitable sponsor — usually a parent or close relative — to whom they can be released.

Most children referred to ORR care are placed in permanent, state-licensed child care facilities, which generally make little to no news. But when large numbers of unaccompanied children suddenly arrive at the border ORR has been forced to rely on temporary influx facilities such as the one at Carrizo Springs.

These facilities have drawn scrutiny from both sides of the political spectrum. Not only are they extremely expensive to operate (Carrizo costs between $750-$800 per child per day, approximately three times the cost of a regular shelter) but, because they are often erected on federal property, they are not subject to the same kind of state oversight as permanent childcare facilities.

Kevin Dinnin, CEO of BCFS, told reporters that he can [but declined to] name several elected officials who “praised us the last time and are slamming us this time.” BCFS was also enlisted by the Obama Administration to operate influx shelters following a previous surge in unaccompanied children at the border in 2014.

“It’s sad and I resent it,” he said. Dinnin, whose company also operated the controversial tent city in Tornillo, Texas, said that one of his conditions for opening Carrizo Springs was “broad transparency,” insisting on immediate media tours and visits from elected officials.

While secrecy has done little to help public perception of what ORR does, particularly in the current political climate, it has also hardly been the innocent victim of partisan outrage.

A number of larger shelters including the influx shelter Homestead, Fla., a former Jobs Corps site that has housed over 12,000 immigrant children since last March, have been criticized for allegations of various forms of mistreatment, from prolonged detention to sexual abuse.

Throughout the tour, Weber repeatedly sought to differentiate Carrizo Springs from both CBP facilities and Homestead, which was a stop for many 2020 Democratic candidates before and after last month’s primary debates in Miami.

At one point, he noted an amorphous group of girls en route to one of the classroom trailers and said proudly, “Kids don’t walk in straight lines here,” referring to widely circulated photos of children walking in single file between the massive bunk-filled tents at Homestead.

Overall, Carrizo Springs seemed a noticeably more welcoming and relaxed place than what is known about Homestead or the now-shuttered influx shelter in Tornillo, Texas — a sprawling tent city that, at its peak, held close to 6,000 thousand kids. But Carrizo Springs had been open for barely more than a week at the time of the tour and was only occupied by a fraction of the kids it has the capacity to house. For now, at least, all of the beds are inside the newly renovated and relatively spacious dormitories.

The only soft-sided structures currently on the property hold the clinic and infirmary, intake center, and dining hall, which doubles as a gym. During the tour, a group of girls who’d just left math class were sitting at long white tables waiting for a dance class to begin. Posters explaining in English and Spanish how to report sexual assault hung inside almost every structure at Carrizo Springs, and Weber noted that two adult care providers are required to escort a child to the medical clinic. There’s “never a child left alone with one adult” he said, explaining that this policy was “all about preventing allegations.”

Between the explosion of red white and blue that was clearly the product of a Fourth of July-themed coloring contest, a closer examination of some of the drawings posted beside the Wayfair bunk beds seemed to offer a more personal glimpse at the children who occupied them: pictures of Jesus, Spanish-language bible passages, chapin and catracho, colloquialisms meaning “Guatemalan” and “Honduran.” Taped on the wall next to one girl’s bed was a sheet of pink paper covered in hearts and the words Papi, hermanitos, familia, te amo and los extraño,” or “Daddy,” “little brothers,” “family,” “I love you,” and “I miss you.”

Alongside a drawing of Bart Simpson, one boy had drawn another of a minion, the popular yellow cartoon character, wearing prison stripes behind bars. Beneath the minion were the words “Welcome to SWK,” an apparent reference to Southwest Key, one of the major (and more controversial) operators of several large, permanent ORR-funded shelters in Arizona, Texas and California.

Inside one of the classrooms, a group of boys were learning U.S. geography by copying a map of the states that had been drawn on the large whiteboard at the front of the room. In another, the male students had been given a word finder puzzle with a drawing of the Statue of Liberty on it. Many of the sheets appeared to be unmarked, while a few had been turned into paper airplanes. Asked whether the puzzle was difficult, one boy, who said he was from Guatemala, nodded and pointed to the words at the bottom of the page. “I don’t understand these,” he said in Spanish.

In another apparent attempt to differentiate Carrizo Springs from detention facilities at the border, which are notoriously kept at extremely cold temperatures, Weber noted that the structures here are kept much warmer to accommodate the children, who are not used to air conditioning and often complain that they are cold. Many of the children seen during the tour wore long-sleeved shirts, however, and one group of girls burst into giggles when asked whether there they were cold. “No, it’s so hot out,” one of them replied in Spanish, explaining that the long sleeves were to protect her skin from tanning.

Another girl complained about the heat in the Texas sun. She said she’d soon be joining family in Alabama.

While Weber and Dinnin both say they hope to see facility quickly emptied out, it’s clear that they expect to welcome many more kids here before that happens. So far, Weber said that all of the children who’ve been placed at Carrizo Springs came from other ORR facilities and are expected to be released to a sponsor soon. However, the medical center was being stocked with vaccines in anticipation of receiving kids directly from the border.

Dinnin is also advocating to keep Carrizo Springs open as a relocation center in the event that Homestead, which has been in the path of previous tropical storms, is evacuated. If necessary, Dinnin said he could increase the capacity at Carrizo Springs to house an additional 2,000 evacuees on top of the 1,300 design capacity. To do so, he said he’d start by emptying out the classroom trailers and filling them with bunk beds, though ultimately, he acknowledged that tents might be needed to accommodate that many kids.

“Tents should always be a last resort,” Dinnin said.

Employee outrage may not have stopped Wayfair from providing BCFS with the black metal framed bunk beds and new, white mattresses that filled the dorms at Carrizo Springs. But last month, pushback from local advocates against the government's migrant detention policies was enough to make Lutheran Services in Iowa, one of the state’s largest non-profit human service providers, abandon a grant proposal to house unaccompanied children in ORR custody in two of its existing residential treatment centers for children with behavioral difficulties. The fewer beds available in smaller, regulated facilities run by child service providers like Lutheran Services, which are generally considered preferable, the more HHS will be forced to rely on large influx shelters like Carrizo Springs.

“It’s not a good thing for children to be in mass facilities for any extended period of time,” said Mark Greenberg, who served in the Obama administration as acting assistant director of HHS’s Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which includes ORR. But, he said, despite their high cost, lack of independent oversight and inability to provide the same quality of services available in smaller shelters, “the reality is that sometimes HHS has had to turn to influx shelters because there isn’t enough shelter capacity elsewhere. The alternative would be for children to be staying in [U.S. Customs and Border Protection facilities], and it’s important to get children out of CBP facilities as quickly as possible.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: