Graphic Novel Shows How the Black Panthers Foreshadowed the BLM Era

Fred Hampton was the 21-year-old chief of staff and national spokesperson for the Black Panther Party when, on the morning of Dec. 4, 1969, Chicago police broke into his apartment and murdered him. Hampton was considered a charismatic danger by the Chicago PD and the FBI, a successful organizer whose leadership of the militant group constituted a threat to society. He had to go.

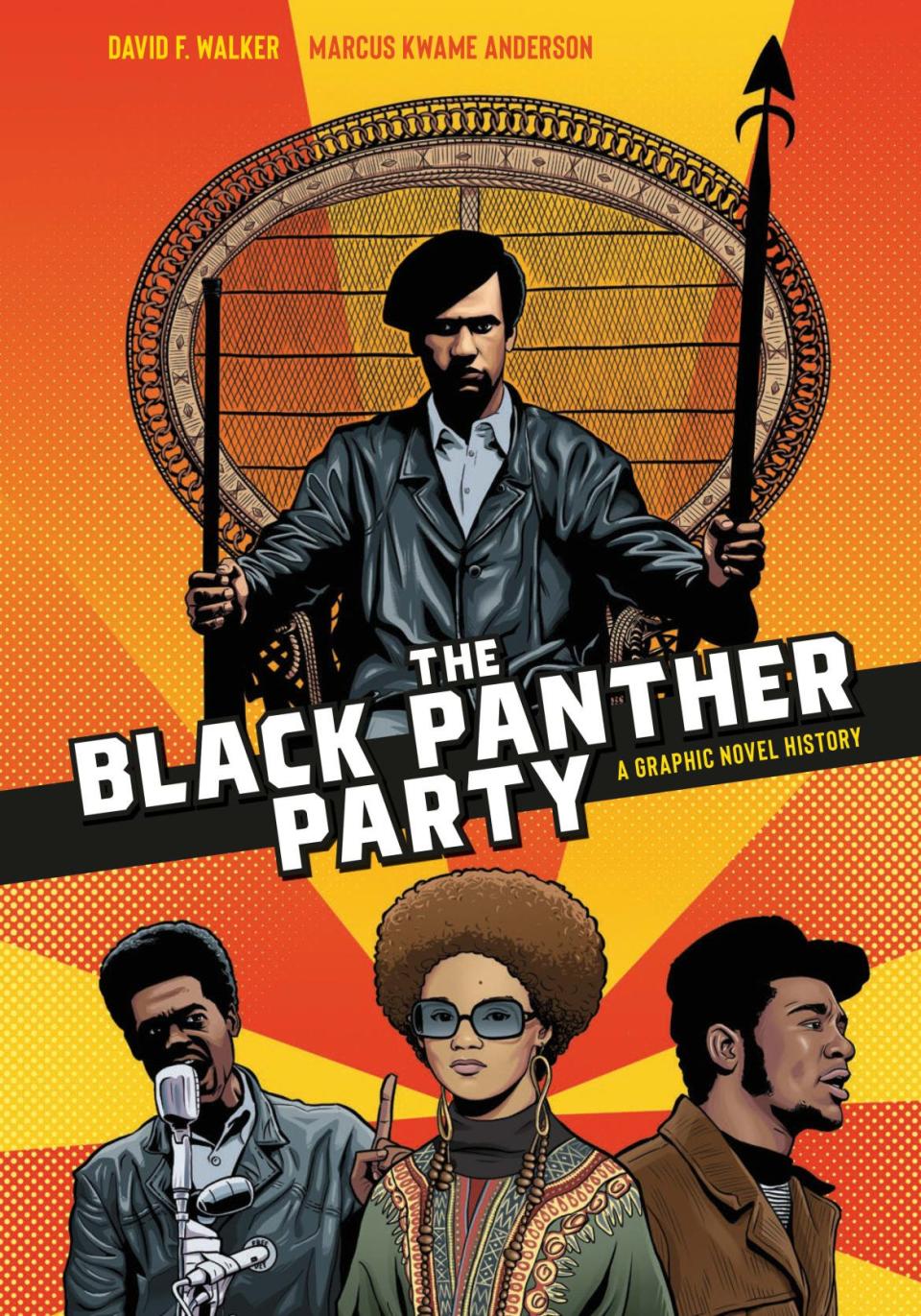

For author David Walker, Fred Hampton’s murder 50 years ago was not ancient history, but a totally relevant story he had to write about. “Fred Hampton was a story I wanted to tell so badly, but to tell that story without contextualizing it would be a mistake,” says Walker, who, along with illustrator Marcus Anderson, is the creative force behind The Black Panther Party, a beautifully conceived and sobering graphic novel tracing the history of this doomed, but influential, group.

“Especially in the aftermath of the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the BLM protests and the response by law enforcement, that has opened the eyes of people who didn’t have their eyes opened before,” adds Walker, “and everything the Panthers fought about and talked about, is happening right now. We’ve been building towards this for a very long time in our society.”

Ex-Black Panther Leader Elaine Brown Slams Stanley Nelson’s ‘Condemnable’ Documentary

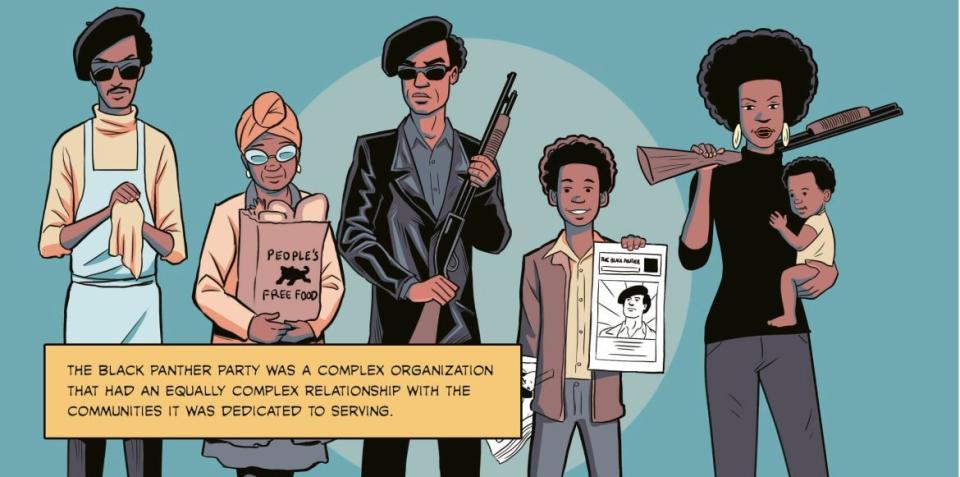

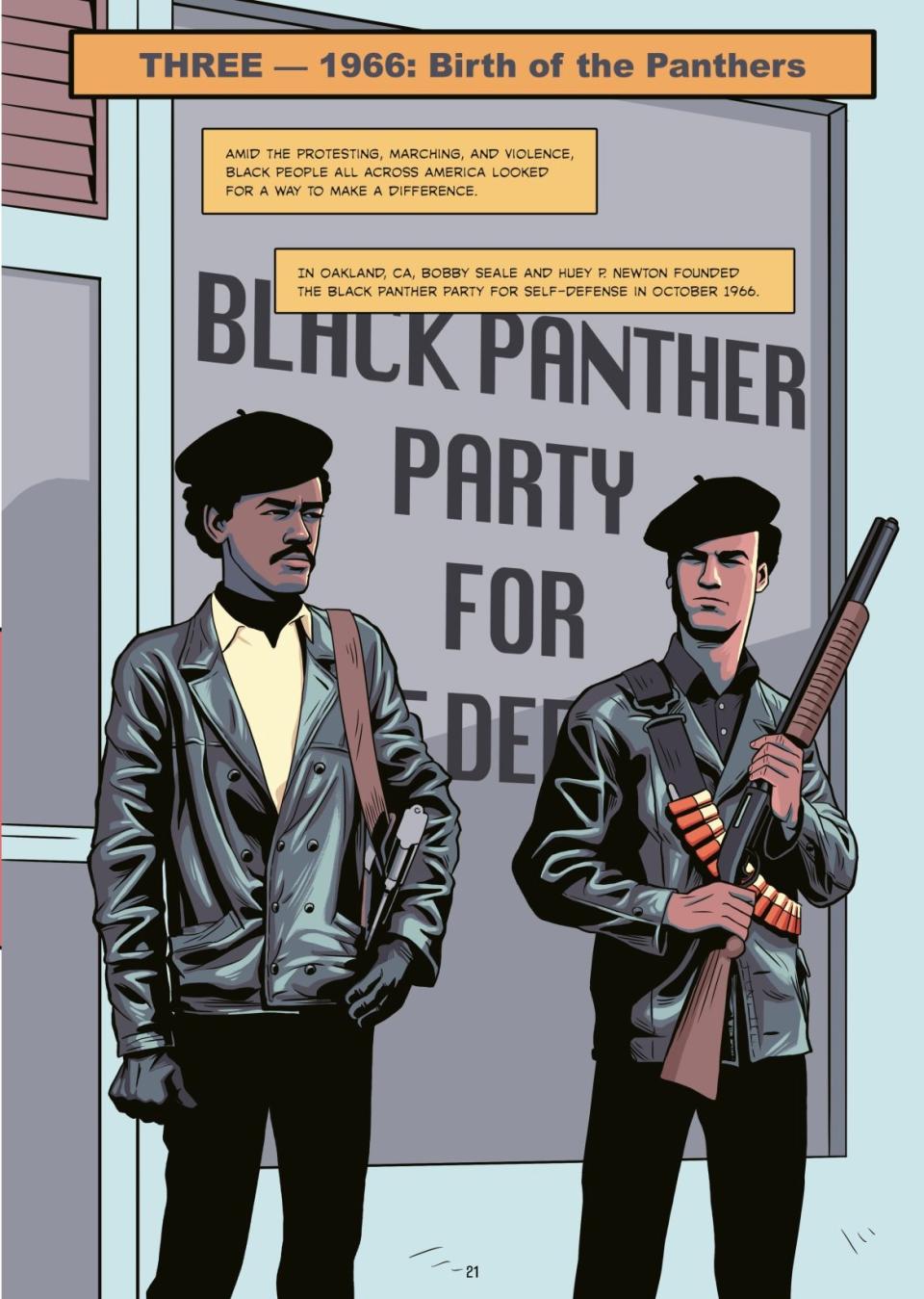

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in 1966 in Oakland, California by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale (‘For Self-Defense’ was dropped from the name two years later). Inspired by the Black Power movement and the racism and brutality of the local police department, the group became famous for its militancy, sartorial style (black berets and leather jackets), weaponry, and a 10-point program that called for everything from decent housing and full employment to an end to police brutality and the release of all Black men from jail. The Panthers also became known for their numerous “survival programs,” which included free breakfast for kids, health clinics, schooling, and a sickle cell testing program. At one point the Panthers had more than 60 chapters nationwide, and influenced similar groups geared towards Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, and Native Americans, as well as organizations in countries including Great Britain, Australia, and India.

“Their youthful enthusiasm and vigor was a real positive,” says Anderson, “and that was also one of the things that was most detrimental. Things like the breakfast programs, the fact those ideas were things that needed to be addressed on the community level.”

“Up until that time, no one had done things like the Panthers did, with that ferocity,” adds Walker. “There was this feeling of being invincible, and it was these factors that worked for and against them.”

Not surprisingly, an organization of militant young Blacks soon caught the attention of the police and J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, whose COINTELPRO program set out to destroy the Panthers and other civil rights groups through a series of covert and illegal acts. That, plus the destructive behavior of some of the Panthers (Newton became a drug abuser) and personality dynamics causing friction involving some of the group’s leaders, led to the Party’s ultimate destruction—by 1977, it was a shell of its former self.

But the legend of the Panthers as take-no-prisoners activists standing up for the Black community has remained, which is one reason why both Anderson and Walker were excited about the Panther project. Walker had just finished The Life of Frederick Douglass,” a graphic novel about the former slave turned abolitionist, and felt “it seemed like a natural transition to go from Douglass to the Black Panther Party.”

Although the duo live at opposite ends of the country—Anderson in New York, Walker in Oregon—they were familiar with each other’s work in the comics and graphic novel fields, and, says Anderson, “at the tail end of 2018 [Walker] had sent some samples of my work to a publisher, but he wasn’t able to tell me what the project was. I was finishing another graphic novel, and he called me with the good news, and that’s when I found out what the book would be.”

The project took over a year to complete, and during that time all the work was done by phone or over the internet. After the script was finalized, “David would send me reference material, images, and we discussed how we wanted to represent things,” says Anderson “He built up so much research on the project.”

“There were a lot of conversations, text messages, and phone calls,” says Walker. “I was always looking for visual reference materials and telling him you might want to look for this or that. And I told him it would take a lot of time, that it would be emotionally draining.”

That emotionally draining element was probably the toughest part of the process for the book’s creators. The oppression directed against the Panthers on the local, state, and federal levels, the members unjustly incarcerated or murdered by law enforcement (Fred Hampton’s was not a singular case), were occasionally tough to deal with.

“A lot of the conversations we had were about the emotional weight,” says Anderson. “I feel on a visceral level, it’s one of the challenging aspects of the book. The Fred Hampton chapter was one of the toughest; I had to get it right, be respectful.”

Luckily, The Black Panther Party seems to have hit a sweet spot in terms of its release. Aaron Sorkin’s film The Trial of the Chicago 7 has drawn renewed attention to Bobby Seale’s racist treatment during that famous miscarriage of justice, and the upcoming film Judas and the Black Messiah is the story of Fred Hampton (played by Daniel Kaluuya) and the informant (LaKeith Stanfield) who betrayed him.

Both Anderson and Walker believe this kind of attention is particularly important because, in Walker’s words, "I don’t think that many young people know about the Panthers. I’m sort of hoping the book, the Sorkin movie, and the Fred Hampton movie will make people curious. I hope it will lead to a historical re-evaluation, especially for young people.”

Despite this, both of the book’s creators agree that there truly is a Panthers legacy, one that continues to influence activists today. “The image [of the Panthers] has 100 percent informed the activism of today,” says Anderson. “I think the boldness of standing up to police with guns is hard to imagine even today. And I think the thing with the programs, there are similar programs today.”

Their legacy is in “grassroots organizing and speaking to the people in a language they understand,” adds Walker. “There’s the popular idea of them carrying guns, but you can go around today and talk to people about the Panthers and you can find adults who say, ‘They fed me when I was a kid,’ or ‘They educated me when I was a kid.’ They talked a lot about issues of class, and looking out for your own. The thing that created them was that harsh reality of living in Oakland. They were from the streets, and they knew how to talk to people from the streets.”

Reprinted with permission from The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History by David F. Walker copyright ©2021. Art, colors, and letters by Marcus Kwame Anderson copyright ©2021. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.