Fired police chief sues Miami, claims commissioners tried to ‘weaponize’ cops against enemies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If Miami commissioners hoped they had heard the last from former police chief Art Acevedo when they fired him in October, they were wrong.

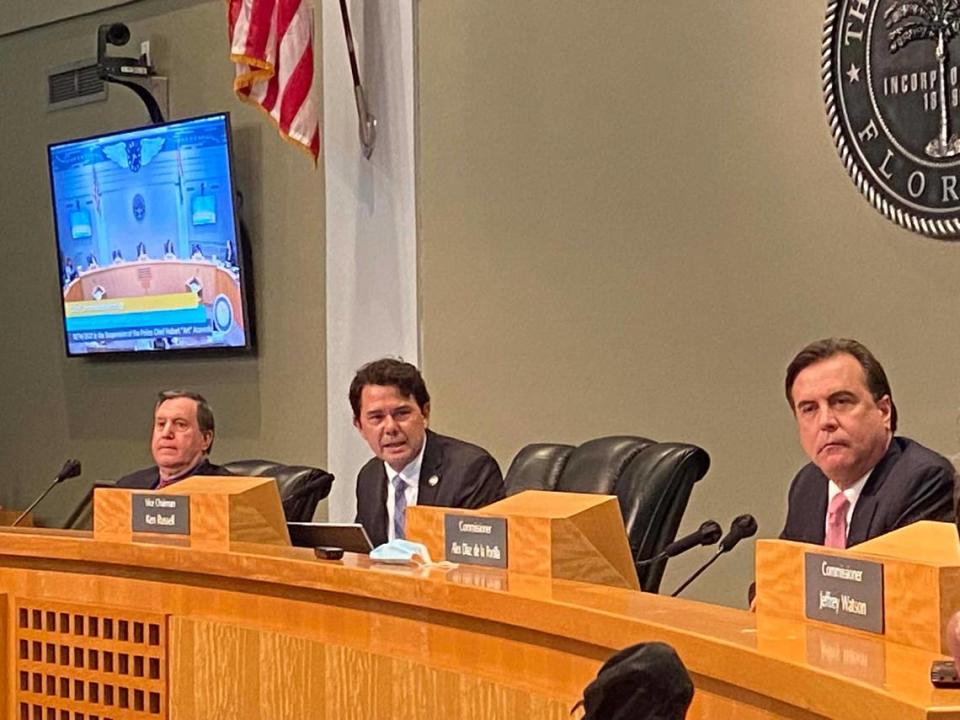

On Wednesday, Acevedo filed a lawsuit in federal court against the city of Miami, City Manager Art Noriega and Commissioners Joe Carollo, Alex Díaz de la Portilla and Manolo Reyes.

In the court filing, Acevedo claims that the city, manager and three commissioners violated his First Amendment rights and illegally retaliated against him for blowing the whistle on what he describes as a toxic stew of corruption and wrongdoing at City Hall. Acevedo says his firing was retribution for trying to maintain his independence as police chief — a stint that started with national headlines for the well-known law enforcement officer but ended in turmoil after just six months.

“After he was appointed Chief of Police, [Acevedo] attempted to promote officers committed to reform, to investigate officer misconduct, and to push back on attempts by certain City of Miami Commissioners to use the men, women, and resources of the MPD ... as their puppet,” the lawsuit states. “In particular, Commissioners Carollo, Díaz de la Portilla, and Reyes targeted Chief Acevedo because of his resistance to their efforts to use the MPD to carry out their personal agendas and vendettas.”

The complaint details several examples of alleged illegal and unethical activity by commissioners, saying they attempted to “weaponize” Miami police officers against their enemies.

Among the incidents:

▪ Using police and code enforcement officers to target businesses owned by Bill Fuller, who co-owns the Ball & Chain nightclub in Little Havana and has feuded with Carollo for years.

▪ Interfering in a police internal investigation into a popular sergeant-at-arms who served as a member of Mayor Francis Suarez’s security detail.

▪ Ordering Acevedo to arrest so-called “communist” agitators at city events. (The suit says they were peaceful protesters.)

Acevedo also claims that he discovered Miami police officers engaged in a “pattern of excessive use of force” and that their commanders had covered it up. He cited one specific case of an officer punching a detained woman in the face after she spit on him and then driving her to the ground, “causing her to lose consciousness.”

The new chief wanted reforms but commissioners stymied his plan to create a position titled Deputy Director of Constitutional Policing, according to the lawsuit.

In an interview with the Miami Herald Wednesday, Carollo denied Acevedo’s claims, saying that it was “an absolute lie” that he ordered the chief to arrest protesters. He also said Acevedo’s accusations that he had it in for Fuller and provided the city manager with a list of businesses to investigate were “outrageous lies.”

“In America, anyone can file a lawsuit,” the commissioner said.

In a statement, Noriega, the city manager, said the lawsuit was no surprise.

“It’s clearly an attempt to retaliate against the individuals that held him accountable for his own shortcomings as Miami Police Chief and to attempt to salvage his professional reputation by casting blame on others,” Noriega said. “I will leave it to our Law Department to address the complaint directly through the proper legal channels.”

Miami City Attorney Victoria Méndez told the Herald that the city wholeheartedly disagrees that there is any basis for Acevedo’s claims.

“We look forward to defending this lawsuit in court,” she said.

Interim Police Chief Manny Morales called Acevedo’s claim that the police department had been weaponized to carry out personal vendettas of elected leaders “an absolute false allegation.”

“I hold the integrity of the Miami Police Department above all else and as one of my top priorities,” said Morales. “I look forward for an opportunity for the truth to come out.”

Díaz de la Portilla responded to questions about Acevedo’s allegations by calling him a “bully, liar, money grubbing piece of crap.”

“We look forward to handling this matter in court,” Reyes told the Herald. “More so, at no time did I give Mr. Acevedo a list of restaurants and bars to investigate. Nor did I give him any directive regarding an internal affairs investigation. We will all have our day in court.”

In a statement, Acevedo’s lawyers Marcos Jimenez and John Byrne highlighted what they termed as the brazenness of the commissioners. They pointed out that Carollo had played the theme from the movie “The Godfather” at the swearing-in of Acevedo’s replacement, Morales — described in the suit as a willing ally of the commissioners.

“Morales pointed at Commissioner Carollo and laughed,” Acevedo’s lawyers said. “The complaint and their public actions say it all.”

Acevedo’s lawsuit states that he gained whistle-blower protections when he complained to Suarez and Noriega about the commissioners in a Sept. 24 memo that he also sent to federal authorities and the Miami-Dade State Attorney.

But instead of protecting him, the suit claims, the mayor and manager told him the commissioners’ behavior “was part of doing business in the City of Miami.”

According to the lawsuit, Noriega later said: “So you’ve gone after them, and better be sure you have a kill shot because if you don’t, you better not take it.”

Suarez, who was in Washington, D.C., for a meeting of the U.S. Conference of Mayors, did not respond for requests for comment.

‘A pretty embarrassing episode’

Acevedo’s lawsuit was expected after the public spectacle of his dismissal from the city in October.

He began to lose good will with Miami’s elected officials just months into his tenure, following a string of public gaffes and controversies, including referring to senior city officials as a “Cuban mafia.” Commissioners began publicly questioning his leadership of the department in late September.

Then, days before an expected showdown over his job at City Hall, Acevedo sent Suarez and Noriega an eight-page memo accusing the three commissioners of interfering with an internal police investigation.

A series of lengthy and sometimes bizarre public hearings followed, with commissioners blasting Acevedo and ordering an internal city investigation. Noriega asked Acevedo for a new plan for policing and how he would run the force. After it was delivered, Noriega said the chief has lost the trust of the rank and file and recommended his dismissal. Commissioners sealed Acevedo’s fate on Oct. 15, capping what the chief later called “a pretty embarrassing episode.”

The chief had tried to fight back, passing his memo to Department of Justice officials in Washington, D.C, as well as the U.S. Attorney and FBI in Miami. But federal authorities expressed little interest in pursuing the case.

Miami-Dade state prosecutors did begin a criminal investigation — but State Attorney Katherine Fernández Rundle soon discovered that the brother of one of her top advisers is a “substantial witness” in the case, according to records obtained by the Miami Herald.

Gov. Ron DeSantis ordered the Broward State Attorney’s Office to take over the case last month.

Acevedo is seeking compensatory damages in his lawsuit. He also noted that, after he was fired, the city tried to charge him $2.3 million for public records in his case.

Several of his actions as chief have been undone since his firing.

Morales, the interim chief, has rehired and reinstated seven of the department’s highest-ranking officers who were let go or demoted by Acevedo. Among them were a married couple, Ronald and Nerly Papier, who were fired after being accused of misrepresenting an April 2 accident in which Nerly Papier crashed her city-issued SUV into a curb on the way to work.