Family secrets will take a seat at every Thanksgiving table – and not just the recipes

My family’s Persian rice is the dish everyone always looks forward to at the holidays. Cooking Persian rice can be an art passed down from generation to generation. But my grandmother didn’t like to share her secret recipes. We, the kids, would sneak into the kitchen, watching her cover the pot with a cloth, as she whispered, “Don’t bother the rice. Let it be.” My grandmother believed that some things needed to be left alone, untouched, and she explained that the round lentils in the traditional Adas Polo rice dish represent the circle of life; you are born and you die, the rest is gravy.

My father immigrated from Iran in 1950 when he was 6 years old. He had two sisters who fell sick and died when they were toddlers, before he was born. As a baby, he was very ill himself and almost didn’t survive. His father, my grandfather, who was blind from birth, needed my father to go to work with him, to sell newspapers on the street.

As a child, I was aware that my father hadn’t gone to school and had worked to support his family since he was young. I grew up with the feeling that he longed for us, his children, to get the education that he could never afford for himself.

Like my father, my mother had also struggled as a baby with life-threatening illness. She lost her oldest brother when she was 10 years old, an enormous trauma for the whole family. My mother didn’t share many childhood memories and therefore those are unknown to me. I wonder if my parents ever realized how similar their histories were, how their bond was silently tied with illness, early loss, poverty, and the pain of racism and immigration.

Silence: the best way to forget trauma

Like many other families, our family colluded and shared the unspoken understanding that silence was the best way to erase what was unpleasant. The assumption in those days was that what you don’t remember won’t hurt you. But what if what you don’t remember is, in fact, remembered, in spite of your best efforts? What if what we bring to a holiday table isn’t only the dish that is passed down from generation to generation, but also our family legacy and our emotional inheritance?

I was my parents’ first child, and even though they might like to leave that past alone, I grew up with the feeling that life was fragile, that loss was possible, that we must be vigilant against tragedy. Their silenced traumatic past lives in my body.

How do we inherit, hold and process things we don’t remember or didn’t experience ourselves? In the last decade, contemporary psychoanalysis and empirical research have expanded the literature on epigenetics and inherited trauma, investigating the ways in which trauma is transmitted from one generation to the next and held in our minds and bodies as our own.

It was after World War II that psychoanalysts first began examining the impact of trauma on the next generation. Many of those analysts were Jews who had escaped Europe. Their patients were Holocaust survivors and later the offspring of those trauma survivors, children who carried some unconscious trace of their ancestors’ pain.

Starting in the 1970s, neuroscience validated the psychoanalytic findings that survivors’ trauma – even the darkest secrets they never talked about – had a real effect on their children’s and grandchildren’s lives.

In the '90s, relatively new studies were focused on epigenetics, the nongenetic influences and modifications of gene expression. They analyze how genes are altered in the descendants of trauma survivors such as war veterans, enslaved people and Holocaust survivors. Those studies highlight the ways in which the environment, and especially trauma, can leave a chemical mark on a person’s genes that is passed down to the next generation.

Aswad Thomas: Thousands of kids experienced, saw gun violence last year. How are we dealing with trauma?

This research is not surprising for those of us who study the human mind. Every family carries some history of trauma, and in our clinical work, psychotherapists see how traumatic experiences invade the psyche of the next generation and show themselves in uncanny and often surprising ways.

The people we love and those who raised us live inside us; we experience their emotional pain, we dream their memories, we know what was not explicitly conveyed to us, and these things shape our lives in ways that we don’t always understand.

We carry emotional material that belongs to our parents and grandparents, retaining losses of theirs that they never fully articulated. We feel these traumas even if we don’t consciously know them. Old family secrets live inside us.

Policing the USA: In face of violent crime and COVID trauma, nation can't fall into overincarceration trap

In my clinical work, I observe how often it is our emotional inheritance that prevents us from following our dreams, from creating, loving and living to our full potential. It is the stories that have never been told that leave us undone. Those parts of ourselves are our family legacy that we carry like a hot dish we then unconsciously serve to the next generation.

The molecular implications of trauma

This framework for understanding how nature and nurture intermingle and how we respond to the environment on a molecular level is profound; we realize that trauma can be transmitted to the next generation, but also that emotional work can alter and modify the biological effects of trauma.

While our journeys to healing vary, each starts with the decision to search, to open the door, and rather than turn away from the hurt of the past, to walk toward it. We choose to look straight into the eyes of the past and unpack our emotional inheritance, to be active agents in transforming our fate into destiny.

Trauma is transmitted through our minds and through our bodies, but so are resilience and healing. Analyzing the emotions we might pass on to the next generation is a step toward breaking the cycle of intergenerational trauma. Our hope lies in the understanding that our awareness has a profound effect on who we, our children and our grandchildren will become.

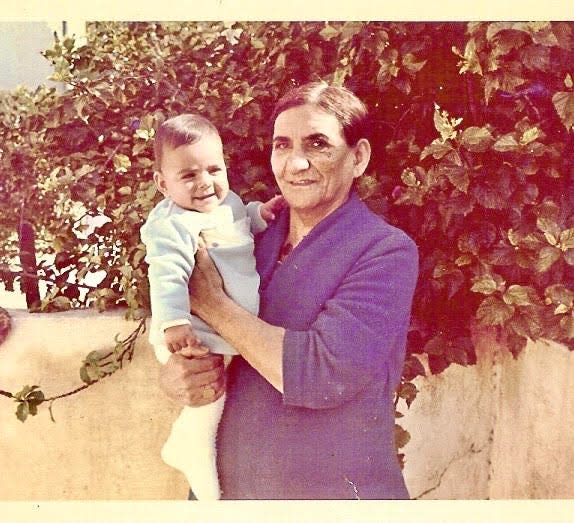

My grandmother’s recipes were not the only secrets she kept from us. She didn’t want to burden us with her past and believed in optimism. Towards the end of her life, I was able to step into her kitchen and collect reminiscences of her history, get a taste of her truth, listening to the omissions, to stories untold. And I followed her cooking and wrote down her legacy that she trusted me to bring to the table.

Galit Atlas is a psychanalyst practicing in New York. She is a clinical assistant professor on the faculty of the New York University Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy & Psychoanalysis. Her upcoming book is called "Emotional Inheritance: A Therapist, Her Patients, and the Legacy of Trauma."

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Epigenetics shows that survivor trauma persists throughout generations