Failure to stop thieves and burglars threatens police’s ‘bond of trust’ with the public

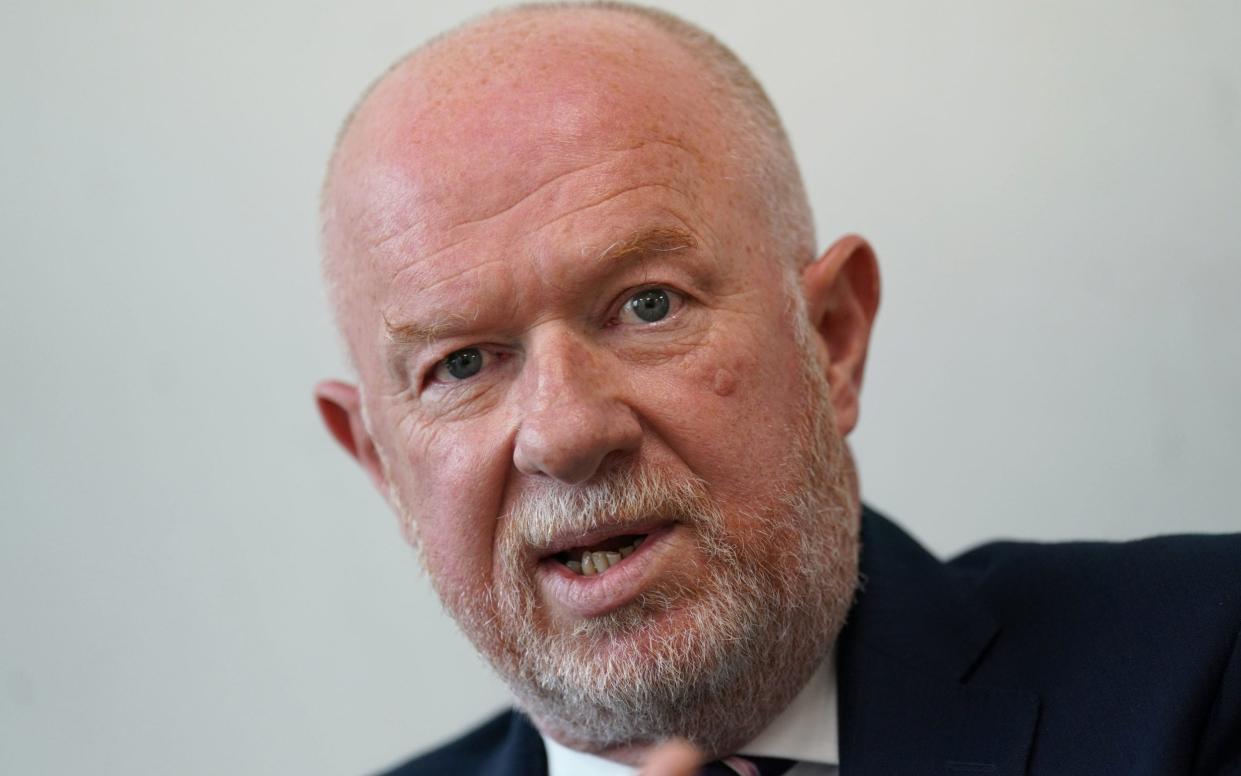

A failure to stop thieves and burglars threatens police’s “bond of trust” with the public, HM chief inspector of police has warned.

In an article for The Telegraph, Andy Cooke said most victims of burglary and theft were being denied the justice they deserved because of police officers’ failure to do the basics in investigations.

He said police were “setting themselves up to fail” from the moment they took a 999 call, because they were missing opportunities to gather vital evidence and identify offenders.

This ranged from 999 call staff failing to tell victims how to preserve evidence at burgled homes not being visited by police, inexperienced officers leading investigations unsupervised, and householders not being told how to prevent thefts, according to his report published on Thursday.

Too many offenders were at liberty due to “unacceptable and unsustainable” rates of solving crimes, he said, with fewer than one in 20 thefts (4.2 per cent) and one in 15 burglaries (6.6 per cent) resulting in a criminal being caught and charged.

Mr Cooke warned that unless there was a “concerted and focused” drive by police to “get back to the basics” of thoroughly investigating theft and burglary, “the public is likely to lose confidence in forces’ ability to keep them safe”.

He added: “Public confidence in the police is more than precious - it is essential. One of the most important ways to maintain this essential bond of trust is for the public to know that if they are a victim of crime, that the police will take it seriously, investigate it and bring the offender to justice.

“This unspoken agreement applies to all crimes, including burglary, robbery and theft of and from a motor vehicle. These crimes have increased dramatically. Between March 2017 and Sept 2019 alone, they went up almost 25 per cent.”

Mr Cooke said calling theft and burglary “volume crimes'' failed to recognise they struck at the “heart of people’s feelings of safety and security”.

He said: “Many victims are targeted more than once, repeatedly made to feel unsafe. But these crimes are not always getting the time and attention they deserve.”

He revealed that in 71 per cent of burglary reports inspectors examined, police had not given victims any advice on how to preserve the crime scene during their initial call - meaning vital evidence could be lost or degraded. Vulnerable and repeat victims were often not properly identified.

In the face of a national shortage of detectives, cases were being given to newly-trained officers who had no experience in making arrests, building case files or attending court.

A third of the cases inspectors examined were inadequately supervised, increasing the risk of missing opportunities to uncover evidence and intelligence to link cases through CCTV, witness statements and door-to-door enquiries.

After the disclosure by The Telegraph that officers visit as few as one in four burglaries, Mr Cooke said he expected forces to attend every burglary to garner evidence.

“If I was burgled, I would fully expect to see a police officer there not because of what I do, but as a member of the public,” he said.

Police were also hampered by outdated technology, meaning it could take months to conduct basic examinations of mobile phones - with many forces not having enough officers trained to use the kiosks to extract the data. In some, forces finger identifications could take six months.

In one burglary, an investigation was still open two years after the offence, even though officers had identified a suspect. “The victim in this case had complained about the lack of progress,” said the report.

Up to 30 per cent of victims were also being denied their rights under the victims’ code, because police were failing to keep them updated about the progress of their case.

The inspectors found only 13 of 20 forces inspected could show they had consulted burglary victims and effectively recorded their views.

It meant victims faced a postcode lottery of vastly different experiences depending on where they lived in England and Wales, he said.

Only a handful of the 22 police forces inspected for his report into “acquisitive crime” were rated “good” or “outstanding”, with the rest judged as “requiring improvement” or “inadequate” in tackling theft and burglary.