Elwood Jones' impending execution and why it may not matter if the jury was wrong

Here’s a lesser-known fact about the criminal justice system: Once you’re convicted of a crime, it no longer matters much if you’re innocent of it.

Innocence on its own won’t get you a new hearing or a new trial. Even if you’re lucky enough to have money to pay for post-conviction lawyers – or if you find lawyers willing to work for free or through a nonprofit organization like an innocence project – they can’t do much for you based only on your adamant and persistent insistence that you didn’t commit the crime. Even if you've been saying it for nearly three decades.

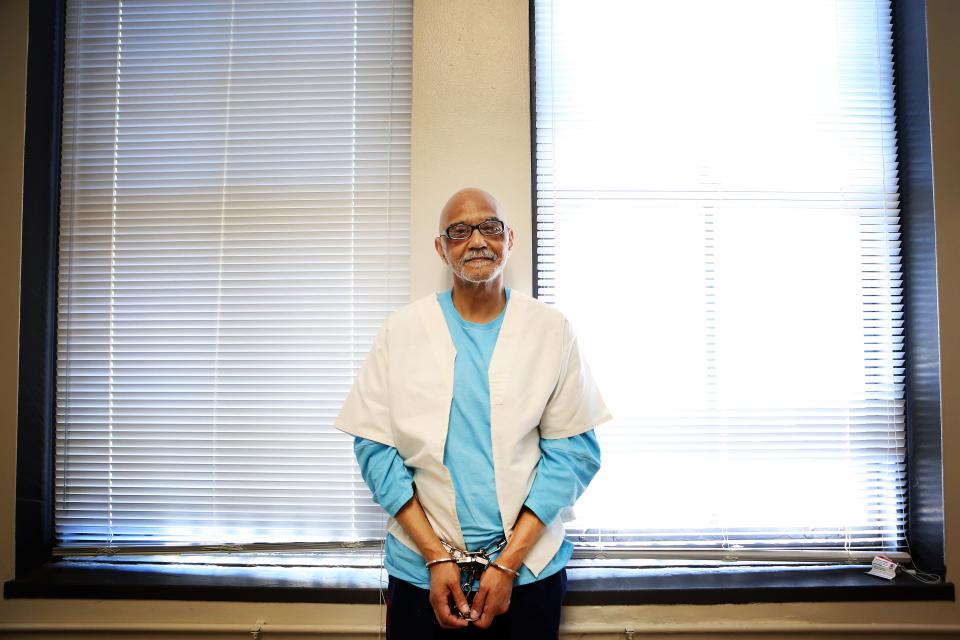

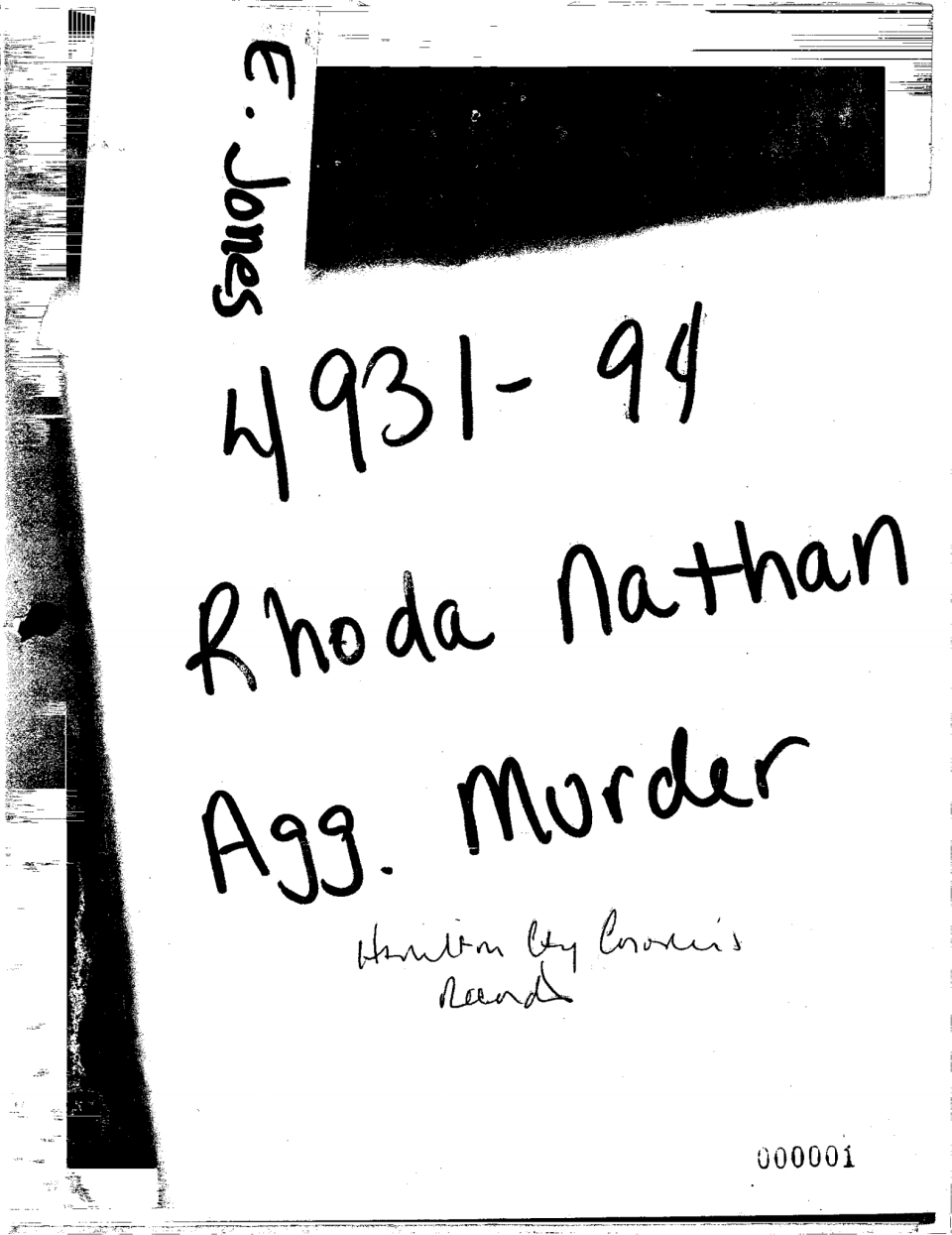

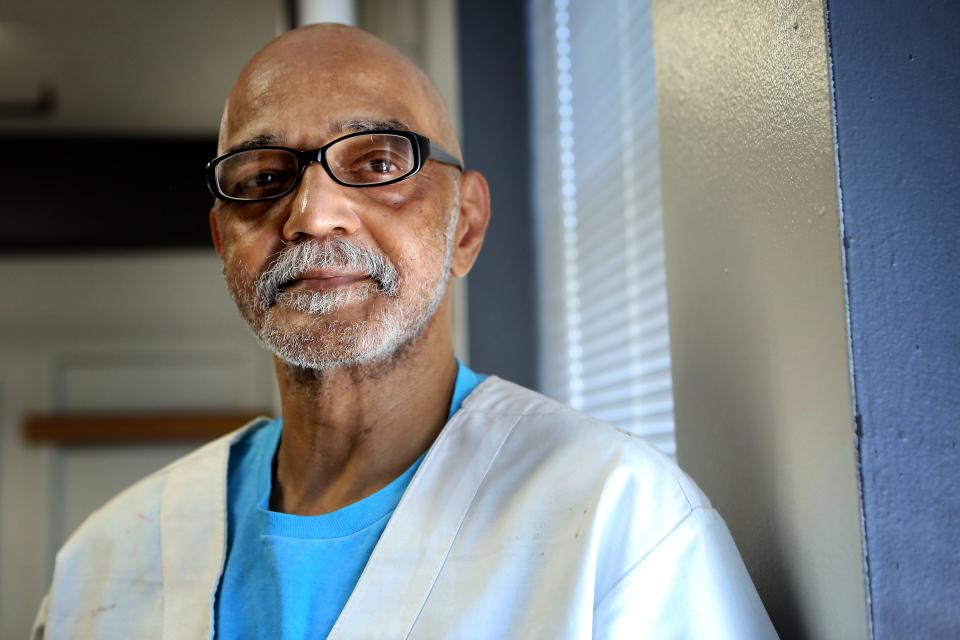

That's how long Elwood Jones has maintained he is not responsible for the death of Rhoda Nathan in a Blue Ash hotel room in 1994, despite what police, prosecutors and a jury maintained since his arrest and trial the year after the slaying.

Once convicted, Jones has learned, it's very, very hard to argue that you're innocent.

So the lawyer representing Ohio death row inmate Jones is going at things a little differently.

Listen to the podcast: 'The impending execution of Elwood Jones' is available to subscribers

“I’m all steeped in junk science now,” said Erin Barnhart, Jones’ lawyer, who was assigned to him via the Federal Public Defender Office of the Southern District of Ohio.

That's what going to be talked about this week when Jones, against all odds, gets a new day in court.

The junk science aspect is related to what court watchers recall being the most damning evidence against Jones during his trial: an infection in his dominant hand that, according to a hand surgeon’s testimony, was teeming with a bacteria called eikenella corrodens – which the surgeon said most likely came from the mouth of his 67-year-old victim, Rhoda Nathan.

It’s this evidence that landed the case on the TV show Forensic Files (season 6, episode 22: “Punch Line”). As Enquirer reporter Dan Horn said in that episode, which originally aired in 2001: “The doctor was very compelling in court when he said there is no other way it could have been infected other than from a human mouth.”

Twenty-seven years later, Barnhart is set to argue that isn’t true during a three-day hearing scheduled for the end of August, the outcome of which will determine whether Jones gets a new trial.

Jones, 70, has been on Ohio’s death row since 1996 after a jury found him guilty in the beating death of a New Jersey grandmother who’d traveled to Blue Ash, Ohio, for a dear friend’s grandson’s bar mitzvah.

Jones was convicted by a jury. Legally, he is guilty of the crime.

An investigation into the case for the fourth season of The Enquirer's podcast Accused doesn't dispute that. But it doesn't confirm it, either. It did show that mistakes were made in the investigation and trial, suspects were not all thoroughly vetted, all leads not followed.

A few stories have changed. But not Jones'.

But the fact is that what Jones says doesn't matter. That was true before a recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling said as much – see Shinn v. Ramirez and Jones – when the majority ruled that it could only weigh whether a death row inmate had been effectively represented by his counsel and not whether there was overlooked evidence that he was innocent of the crime.

See the crime scene:Step inside the crime scene at the heart of 'Accused: The Impending Execution of Elwood Jones'

This is why Jones’ repeated attempts to get a new trial have never been over-reliant on his claims of innocence. To get a new court hearing, he must convince a judge not that he didn’t commit the crime, but that the trial leading to his conviction was flawed.

The odds are not in his favor, but in fairness, neither were the odds that he’d be granted a hearing to even make the argument. He had exhausted all of his appeals to no avail, but then, in November 2019, he was granted a hearing to argue for a new trial.

That hearing was supposed to come in 2020, but was punted to 2021, and then punted further thanks to the pandemic. It’s now scheduled for this week, and while nothing is guaranteed, it looks likely to proceed as planned.

The outcome of the hearing could determine whether Jones gets the one thing he’s requested since his conviction: a new trial. Those who oppose a new trial – specifically, officials with the Blue Ash Police Department and the Hamilton County Prosecutor’s Office – say their reason is simple: Jones’ legal arguments don’t matter, they say, because he is, in fact, guilty.

All this highlights an often-overlooked conundrum in American judicial system: When defendants claim their verdicts should be reevaluated because they’re actually innocent, they’re shot down by a system that argues actual innocence can’t be weighed post-conviction without new and convincing evidence. Yet when defendants present arguments about the legal process that convicted them, they’re often told those issues don’t matter because they’re guilty anyway.

If it’s a confusing sentiment to read, imagine living it.

But first, let’s back up and tell the story that has led to Elwood Jones’ last stand.

The visitor

Labor Day weekend of 1994 was a busy one in metro Cincinnati for a lot of reasons. For starters, the long holiday weekend was bound to entice travelers. That was a given.

But in Cincinnati specifically, there was more going on: The Sunday before the holiday,the city would host its annual Riverfest, a daylong celebration marking the end of the summer. The highlight would be the Rubber Duck Regatta, one of those you’ve-gotta-see-it-to-believe-it experiences in which revelers release hundreds of thousands of rubber ducks into the Ohio River. The festivities always wrap with fireworks.

It's been a popular draw every year – excepting 2020, when the pandemic cancelled it – drawingsome 500,000 visitors. In 1994, only a fraction of those people could fit into downtown Cincinnati’s approximately 4,000 available hotel rooms. As such, out-of-towners inevitably spilled into hotels throughout the suburbs.

In short, hotels were packed, but that didn’t stop some folks from planning overlapping non-Regatta events in the area. Like bar mitzvahs.

That’s what drew 67-year-old Nathan to the region.

Nathan was a New Jersey native whose husband of 45 years, Robert, had died just two years earlier. The couple had two sons, whom they raised in a tight-knit Jewish neighborhood called Greenbriar Woods. The family was somewhat high profile thanks to the successful hardware store that Robert Nathan ran. Meanwhile, Rhoda Nathan stayed active well into her retirement. She’d been president of a community drama club and a member of the bridge and tennis clubs.

Nathan’s best friend for most of her life was Elaine Shub, and it was Shub’s family that drew Nathan to the Cincinnati region that weekend. Shub’s grandson was turning 13. His bar mitzvah drew quite a few people from across the country, including family friend Dorothy Cantor.

“The parents of the bar mitzvah boy had lived in our town in New Jersey, and that’s how we were connected,” Cantor said. The “we” to whom Cantor refers is herself and her late husband, Gerry.

The Cantors learned just before their trip that another bar mitzvah guest would be on their same flight into town, so they agreed to find Nathan on the plane and share a cab from the airport to the Blue Ash Embassy Suites hotel. They’d never met Nathan before. They had no idea that after they helped her check in and said goodnight, the next time they’d hear her name was to learn that she was dead.

“We were stunned. Shell-shocked, disbelieving, you name it," Cantor said. "We were incredulous.”

The Cantors had only met Nathan. Others gathered for the weekend’s festivities knew her well. Elaine Shub had shared a bed with her the night before. The two were platonic friends – Shub’s boyfriend, Joe Kaplan, shared the suite with them – but the women had known each other so long, feeling more like sisters than friends, that it was a no-brainer for the two to share the suite’s main bed while Kaplan slept on the pull-out mattress in the sitting room portion of the suite.

As shocked as the Cantors had been at news of Nathan’s death, Shub was inconsolable.

“My mother was never the same after that day,” said Shub’s daughter, Cynthia Kirsch.

Kirsch, 67, was staying at the Embassy Suites for the bar mitzvah celebration, too. She and her husband, Jeffrey, and their young son had a separate room next door to her mother. In fact, it was Kirsch’s 6-year-old son who’d turned a key to his grandmother’s room door and pushed it open to reveal the nude, battered body inside.

The crime

Most Embassy Suites hotels share an aesthetic: The rooms hug the building’s exterior and encircle an atrium that spans all of the floors, so every room opens into a hallway that overlooks a shared open space. Sometimes that open space houses a pool, so guests wander into the hallway and are hit with a tropical ambiance as hotel guests splash in the water and lounge in recliners poolside.

The Blue Ash location has a pool, but it’s housed in a separate nook on the west side of the building. The open space in the Blue Ash location is used instead for one of the hotel’s most popular features: its breakfast service.

During non-breakfast hours, the space is generally quiet, but not so when cooking is underway. The whole atrium teems with guests lining up to fill their plates with yogurts and pastries or made-to-order omelets. Hotel staff bustle about, some working the omelet station while others hurriedly clear vacated tables to make room for incoming guests.

The morning of Sept. 3, 1994, Kaplan and Shub had gone to breakfast without Nathan, who was slower to rise. That was typical for Nathan, as her friend well knew, so Shub didn’t think twice about leaving Nathan in the room to go at her own pace. Shub and Kaplan, meanwhile, were ready for breakfast, as was Cynthia Kirsch, whose husband and son had already gone down to the eating area.

“I went next door to get my mother, and so the three of us walked out of the room,” Kirsch said.

Police would later theorize that someone was watching the room. If that someone had known three people were staying in the room – Shub, Kaplan and Nathan – it might have seemed logical to think the room was left empty now that three people were seen leaving it.

For a brief period, Shub, Kaplan and Kirsch overlapped with Kirsch’s husband and son in the atrium, but then Jeffrey left to return to his room and shower. He said he heard nothing unusual from the neighboring hotel room.

Back in the atrium, nothing seemed ominous. Shub and Kaplan nodded hellos to others in town for the bar mitzvah, which was set to take place in a matter of hours.

The morning was moving leisurely until Kirsch’s son announced he needed to use the bathroom – which, in typical kid fashion, he had to do right that very second. So the quartet – Shub, Kaplan, Kirsch and her child – all went upstairs. They reached Room #237, Shub and Kaplan’s room.

In later tellings – including his trial testimony and during a police interview aired on the TV show Forensic Files – Kaplan would say he turned the key to open his room door, but in an interview with The Enquirer in 2021, Kirsch remembered things differently. The discrepancy matters, but more on that in a minute.

According to Kirsch, her son opened the hotel room door.

“He wanted to be the one to turn the key,” Kirsch said. It was a little-kid desire placated by amused adults who no longer saw the magic in how keys worked. The door swung open and, Kirsch said, “she was right there in front of the door.”

After a beat to register what she was seeing, Elaine Shub unleashed a blood-curdling scream that seemed to suspend time for a split second. She fell to the ground, and the people around her seemed to spring into chaotic action.

At first, the cause of Nathan’s death wasn’t clear, but there were rumblings from the start that it hadn’t been natural. Police descended quickly onto the scene. Cantor remembers debate about whether the bar mitzvah should continue as planned. It was not an easy decision.

“There’s something in Jewish lore – tradition – that says a simcha, which is a happy occasion, always takes precedence over a tragedy to keep you focused on life,” Cantor said. Because of that, the family decided to go through with the bar mitzvah rather than cancel or postpone it.

While their focus shifted to life, police became mired in Nathan’s death.

The confusion

Despite what some investigators say today, Rhoda Nathan’s death wasn’t immediately treated by everyone present as likely having been natural, something that caused a fall and resulting facial injury. At least, not according to reports filed and interviews conducted in the aftermath.

Rather, Blue Ash police straight away moved to investigate it as a questionable death – or even a possible homicide – a fact underscored by the agency’s request that morning that the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office send over one of its homicide detectives, Peter Alderucci.

“When I got there, the body was gone,” Alderucci told The Enquirer in a 2019 interview. “Nothing looked like it was disturbed in the room. Her purse was sitting on a shelf, upright and opened, but nothing looked like it’d been disturbed in it.”

Alderucci said he’d requested to watch Nathan’s autopsy at the county coroner’s office but was instructed by his boss to stay at the hotel instead to oversee evidence collection. During that process, police found a loose tooth on the floor. It had apparently been knocked from Nathan’s mouth, though investigators weren’t sure how or why.

“I was there a couple of hours and I finally called to the coroner’s office and talked to one of the attendants there (who) was examining the body for the autopsy,” Alderucci recalled. “And I said, ‘It looks like we’ve got a questionable death, or maybe a heart attack,’ something like that. He said, ‘Are you kidding me? This is a homicide. … All of her ribs are broken. She’s got bruises all over her. Her jaw is broken so bad that the bones were sticking through, into her mouth, her jaw bones. And she had swallowed another tooth beside the one that was knocked out.’

“I said, ‘Sounds like we’ve got a homicide.’”

Here's where memories differ.

Jeffrey Kirsch – the son-in-law of Nathan’s best friend and hotel roommate Elaine Shub – said he remembered it being clear from very early that Nathan hadn’t merely fallen in the room. When Nathan was wheeled out of the room on a stretcher, Shub had yelled, “Her necklace is gone!” Shub then rushed into the hotel room and grabbed her purse.

“She was missing $500,” Jeffrey Kirsch said, “and she started screaming out, ‘They took $500!’ Then, all of a sudden, the yellow tape went up.”

That would have been before Alderucci had arrived.

This chronology matters because police didn’t gather some of the evidence most people would expect them to gather in a criminal investigation. For example, though Shub had claimed money was missing from her purse – implying that the purse had possibly been handled by someone who’d been in the room at the same time Nathan died – police didn’t keep the purse as evidence. Rather, Shub was allowed to take it from the room. It would be two weeks after the murder that Blue Ash police requested she mail it back for fingerprint testing, which would uncover nothing of value.

The area of the room where the purse had been sitting – a bar counter between the living room area of the hotel suite and the bedroom – wasn’t fingerprinted, either. A bloody shoe print found on the tile floor of the bathroom wasn’t measured or secured.

Asked about these omissions later, police said they were understandable oversights given the fact that officers didn’t know they were investigating a crime until hours after Nathan’s body was uncovered. This doesn’t jibe with Cynthia Kirsch’s memory of how things unfolded.

“They closed that room off right away,” Kirsch said. “They didn’t even let my mother get her dress for the affair.”

Kirsch has for decades believed the police’s theory that Elwood Jones murdered Nathan, a woman so ubiquitous in Kirsch’s life that she considered her a second mother. But she’s always had a tough time squaring her memories from that day with claims that the room wasn’t treated like a crime scene straight away.

This sticks out in her memory, she said, because the decision to hold the bar mitzvah despite Nathan’s death put Shub in a bind.

“My mother had to borrow a dress from someone else,” Kirsch said. “They didn’t let her have her dress or her shoes. She couldn’t get any of her stuff.”

Jeffrey Kirsch recalls the same.

“I remember being impressed that they had all this laser equipment that they were bringing in,” he said. “They were doing all kinds of stuff technology-wise in the room.”

But that technology yielded no useful clues. Part of the problem surely stemmed from the crime scene being a regularly frequented hotel room. Nor could it have helped matters that after Elaine Shub screamed, a handful of hotel employees had rushed to the room. Their thoughts weren’t on preserving evidence, they’d later testify. They were trying to save the woman’s life. Jesse Wallace, who’d worked in the kitchen, was among the first to arrive and had previous training as an EMT in the military. He took such command of the scene that his coworkers would later describe him as being “everywhere” in the room until official medics arrived.

(Among Wallace’s life-saving efforts: He could hear her gurgling so he asked a coworker to find a turkey baster in hopes he could suck out the liquid blocking her airway. The kitchen didn’t have a baster, however.)

Wallace would later be interviewed twice in connection with the slaying, but there was no evidence he was involved beyond bolting to save a stranger’s life. He eventually would be called to testify in the trial against his coworker, Elwood Jones.

The cut

Jones wasn’t immediately on detectives’ radar – at least no more than the other dozen-plus hotel workers they'd soon be interviewing. Jones' typical job was to ready the banquet rooms for whatever events were planned that day.

One of those rooms, in fact, would end up being used by police for interviews in the wake of Nathan's attack. Jones helped set up the space, arranging dining tables and chairs to accommodate officers, workers and hotel guests.

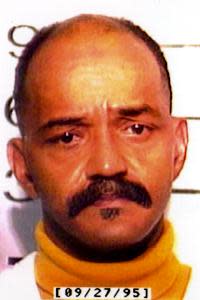

Jones was among the first interviewed and offered little insight into the crime. Nothing about his appearance drew attention, either. Police made no note of whether he’d appeared breathless or disheveled, as one might be expected to appear after brutally beating a woman to death.

At the time of Nathan’s death, Jones was 42. He was common-law married to a woman named Yvonne, who lived with him in an apartment on Moorman Avenue in East Walnut Hills.

But Jones wasn’t an ideal mate. He was having an affair with a coworker named Earlene Metcalf. He would later say that Yvonne knew about the affair and wasn’t thrilled about it, but she tolerated it.

Because Jones and his lover worked together, that meant they saw each other plenty. The morning of Nathan’s murder, Jones had picked up Metcalf and driven her to work at 5 a.m. even though he wasn’t scheduled until later in the morning. When he got there, though, things looked harried and he learned another guy who was scheduled to work wasn’t coming in.

“So my day had to reshuffle,” Jones said.

He got to work, starting in a 900-square-foot meeting room known as the Redwood Room. It was scheduled to be used that day but hadn’t been set up yet, so Jones did that first.

Then, he said, he turned his attention to two big ballrooms beside the atrium.

After that, “I decided to go upstairs and see what was left in these three rooms up there – the Elm, Oak and Maple. I went up to the second floor to look and there was trash.”

None of this was out of the ordinary, and at least two workers confirmed that they’d seen Jones coming in and out of the rooms he described. But then Jones hurt his hand.

His explanation was fairly simple: He said that as he was cleaning these meeting rooms, he filled up trash bags to throw away in a dumpster outside. During one of those trips, he said he fell on some metal stairs leading to the trash bin. In trying to catch himself with his dominant hand – his left – he managed to slice it on the metal stairs instead.

The cut was small. Jones said he washed his hands, slapped a bandage on it and kept working. Not long after, he aggravated the cut a second time while breaking down some banquet flooring.

Afterward, a few coworkers remembered Jones having wrapped the cut with something, though it was a small enough detail that they didn’t remember much about it – like when the injury appeared, for example, or how deep it seemed to be. These might sound like small details, and normally they would be, but for Elwood Jones, the origin of that cut on his hand is literally a matter of life or death.

The suspect

Investigators who interviewed Jones the day Nathan’s body was discovered didn’t make note of his cut hand, but they took notice a few days later when they learned that one of the Embassy Suites’ workers had been injured the same day a woman was brutally beaten in her hotel room.

Nathan had died on Saturday. On Sunday, Jones went to work as scheduled. His hand by then had started to swell but he could still use it. The next day, however, the cut began to hurt enough that it interfered with his job. Jones left early. Then on Tuesday, he finally went to a doctor at a clinic in Norwood.

Accused podcast on Elwood Jones:Elwood Jones claims innocence. He sits on death row

By then, his hand was so infected that it hurt to write, so Jones’ wife filled out the paperwork for him. One of the questions asked if anyone had witnessed the injury. According to her later trial testimony, Yvonne thought that meant people who knew about the injury, not necessarily people who saw it. She said that’s how she conveyed the message to Jones, who told her the names of three coworkers he’d told about the injury after it happened.

Problem was, that’s not what the question asked, and when those three coworkers were asked to confirm that they’d witnessed Jones’ injury, they truthfully said they hadn’t seen it happen. Police took that to mean Jones had lied. So now they had a man with an injured hand who seemed to be lying about how he injured it.

Jones became their primary suspect.

It didn’t help that Jones had a rap sheet. To be fair, several of the people hired to work at the Embassy Suites were felons on parole. In fact, in the years leading up to Nathan's death, hotel management fielded dozens of complaints from guests who said stuff had disappeared from their rooms. (This would later come up in a civil lawsuit filed by Nathan's family that argued the hotel had put guests at risk by hiring so many ex-felons. That suit was ultimately settled for an undisclosed amount.)

The hotel would have been given tax incentives for hiring the hard-to-employ – ex-felons, at-risk youth and veterans among them – thanks to the federal Targeted Jobs Tax Credit enacted in 1978. Some of the criminal histories were pretty petty. Earlene Metcalf, for example, had been convicted of small-scale welfare fraud. But others had more serious records, dotted with burglaries, assaults and robberies.

Jones fell in the latter category. He was a self-described thief who’d target empty homes and businesses. He said his thieving started when he was a teenager.

“Sometimes I think it was, I was fighting against my parents,” Jones said. “It may have been the people I was around or the neighborhood … In the end, it was a bad choice. A real bad choice.”

And not an inevitable one. Jones had loving parents. Both were educators who earned decent salaries and took care of their seven children. Not only that, but mom Edna regularly opened her home to at-risk kids who didn’t get much attention from their own parents. That’s how Jones met Kenny Smith.

“His mother was like a foster mother to me,” Smith said. “She took me in at a very early age.”

Smith said he and Jones “grew up as brothers.” Jones – whose siblings and friends called him by the nickname “Butch” thanks to one sister’s inability to properly pronounce his given name – might have been a bit “mischievous,” Smith said, but he wasn’t a killer.

“I truly don’t believe he did it,” Smith said. “Elwood was a lot of things in his life, he did a lot of wrong things, but I don’t think he’s a murderer.”

Prosecutors are convinced otherwise. Hamilton County Prosecutor Joseph Deters was head of the agency in 1994 when Nathan was killed and pursued the death penalty in the case.

“I think it’s a horrible thing for this community to have out-of-town visitors come here and be brutalized in the nature that she was,” he told reporters at the time. “Hopefully we can bring some justice to this situation. We think the death penalty is the appropriate piece of justice.”

Deters, who declined requests to be interviewed, is still Hamilton’s top law-enforcement official, though he’d left between 1999 and 2004 to serve as state treasurer before returning to win the county post again. Deters is now the longest-serving prosecutor in county history.

During that span, Hamilton County earned what some consider to be a dubious distinction.

"Hamilton County per capita was the No. 1 county in the entire country in terms of putting people on death row, for our population (size)," said Bill Gallagher, a Cincinnati defense lawyer who's routinely tapped to defend clients in capital punishment cases.

The county relied so heavily on the death penalty that it was the focus of a major study authored by professors Catherine M. Grosso and Barbara O’Brien at the Michigan State University College of Law and Assistant Federal Public Defender Julie C. Roberts of the Capital Habeas Unit of the Federal Public Defender for the Southern District of Ohio. The study, published in 2020 in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review, tracked aggravated murder cases in Hamilton County between January 1992 through August 2017 and found evidence of discrimination in charging practices and sentencing outcomes based on both the race of the defendant and the race of the victim.

Because it's an academic study, the findings are a bit dense, but this is the crux: If someone in Hamilton County is convicted of killing a white person, they’re more likely to land on death row than if they killed a Black person. The likelihood of a death sentence was even higher if the suspect accused of killing the white victim was a person of color.

Statistically, if Rhoda Nathan hadn't been white, or if Elwood Jones hadn't been Black, Jones would've been less likely to land on death row once convicted of Nathan's murder.

The evidence

While Deters and the prosecutorial team went for the death penalty, they were pretty sure they had all the goods they needed to ensure the jury agreed. As all trials are, of course, there was a lot to consider. Here is what was argued in 1995.

The pendant

In the two years she was widowed, Rhoda Nathan regularly wore a necklace she’d been given as a gift by her husband, Robert. Its design was unique, with staggered tubular gold bars and a few small gems. Elaine Shub, Nathan’s best friend, said she’d subconsciously registered that the necklace was not around Nathan’s neck when medics wheeled her out of the hotel room after her beating. In a videotaped interview with police, Shub said, “I didn’t think at the time, ‘Oh, where’s her necklace,’ but I know it wasn’t there.”

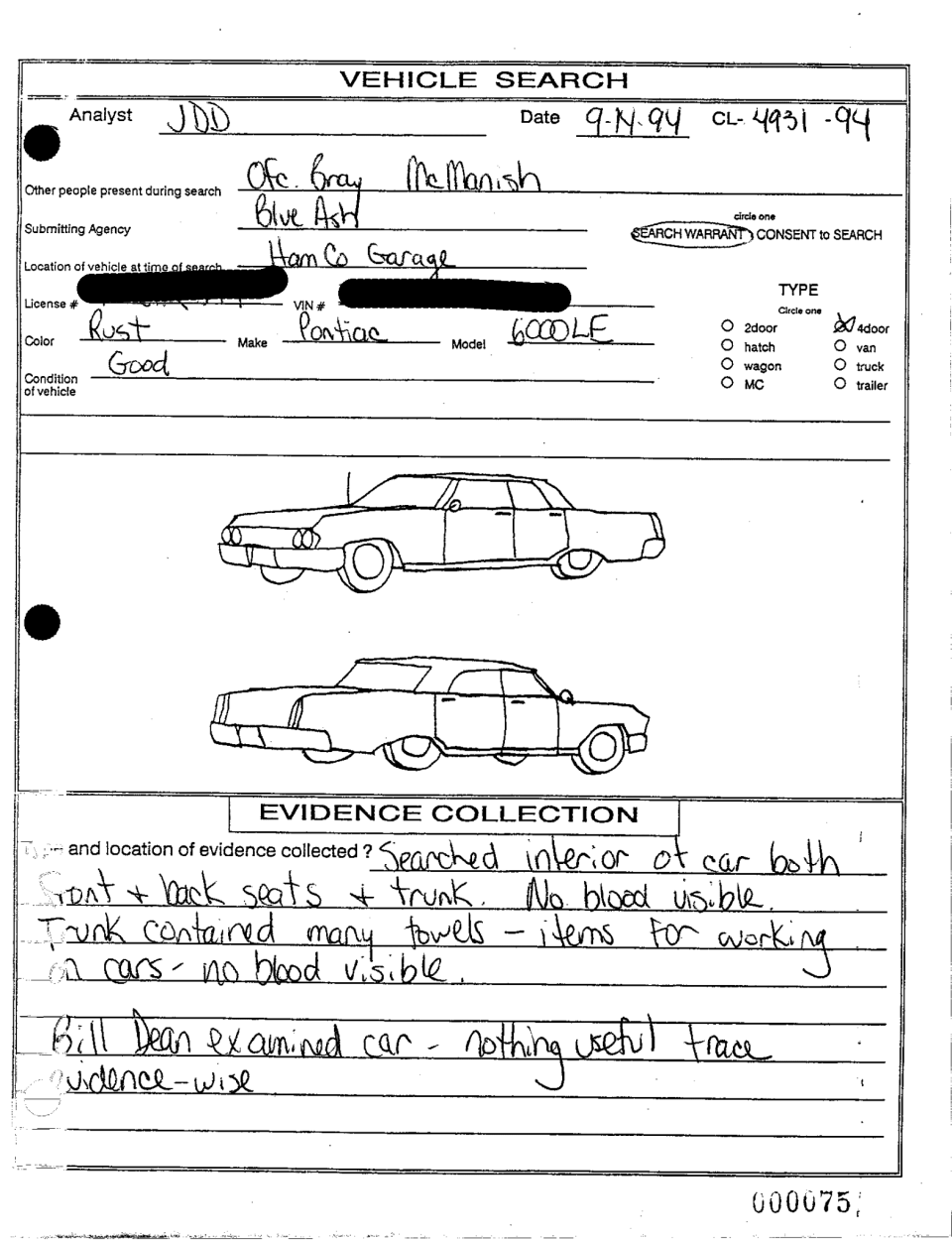

Nine days after the murder, Blue Ash Police Officer Mike Bray conducted a warrant search on Jones’ car, which had been towed from Jones’ girlfriend’s house in Loveland. With no other witness or law enforcement officer present, he searched the car. He said he opened a toolbox in the trunk of Jones’ car, poked around the top drawer of the box with a screwdriver and uncovered the pendant, which he then removed from the toolbox before taking a photograph of it.

Kenneth Lawson, a former Cincinnati-area defense lawyer who initially represented Jones during his pretrial hearings, offered a theory: “They planted that s---.”

'The Investigation': Did police properly secure the crime scene?

Lawson is co-director of the Hawaii Innocence Project and on faculty at the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s William S. Richardson School of Law. Though he quit the case before it went to trial, he represented Jones in early hearings – including a motion-to-suppress hearing aimed to quash evidence gathered from Jones’ car. (The judge ruled against Jones.)

More than a quarter-century later, Lawson said he not only remembers the case but he still believes Jones is innocent – and, more pointedly, he believes Bray planted the pendant in Jones’ trunk to strengthen the case against him.

“I can’t say what his motive was for planting it, but I definitely believe he planted it, and there ain’t no doubt about it,” Lawson said.

Bray cannot respond to the allegation. He died in 2018 of cancer.

During the trial, Jones’ lawyers introduced a witness to cast doubt on the pendant find. They called to the stand a man named Jimmy Johnson who lived near Metcalf in Loveland. Johnson was a dump truck driver who fixed cars for acquaintances as a side hustle. He testified that on Sept. 4, the day after Nathan died, he worked on Jones’ car while it was parked at Metcalf’s house. Johnson said he used Jones’ tools for the fix and had pulled out all the items from Jones’ toolbox to make it easier and faster to find what he needed.

He said that he never saw a gem-encrusted pendant among Jones’ tools.

The bruising

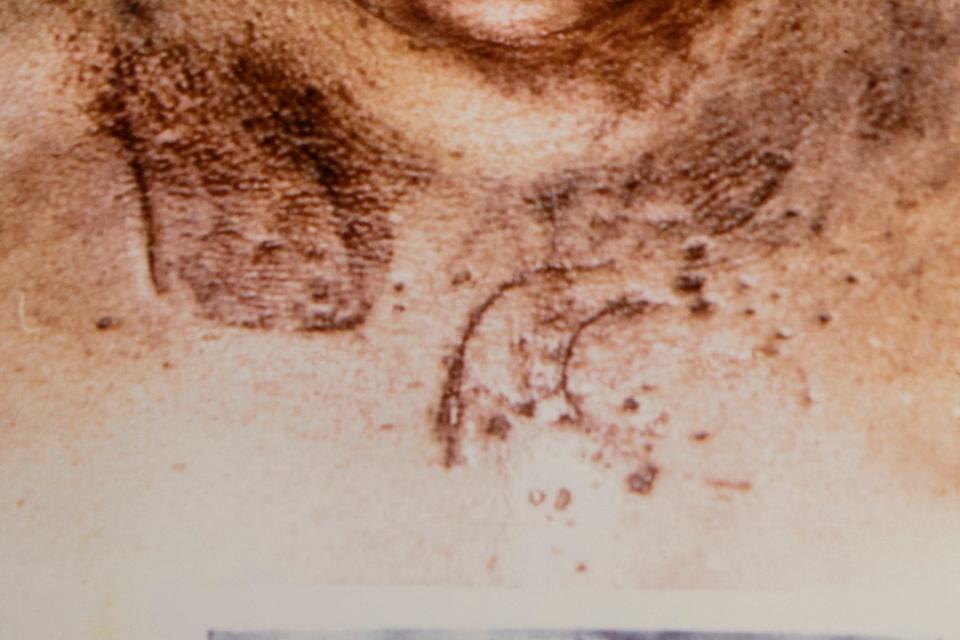

Nathan’s chest and face were smattered with oddly shaped bruises that Blue Ash police – and Officer Bray in particular – believed corresponded with items Jones had in his possession the day of the murder.

Specifically, there was a bruise on Nathan’s chest that Bray believed came from the heel of Jones’ shoe, suggesting that Jones had stomped on her after she fell to the ground. There were also ellipses-like bruises that Bray told FBI lab technicians that he believed were consistent with a length of chain later found in Jones’ toolbox. Nathan’s chest also had rectangular bruises that Bray argued came from the Embassy Suites walkie-talkie that Jones had been assigned the morning of the murder.

During a videotaped deposition, a military pathologist named William R. Oliver – now an affiliate professor at Eastern Carolina University – said he analyzed the bruising. His most damning testimony was that “there exists correspondences in shape and scale between the chain and the marks” and “I could not rule out a correspondence.”

Defense attorney Barnhart said that experts testifying about “a correspondence” between bruising and suspected weapons isn’t definitive enough to put someone on death row, especially when Jones was the only person of interest to have his belongings tested against the patterns on Nathan’s bodies. Other employees were issued walkie-talkies but only Jones’ was analyzed. The same is true for his shoes.

And there were other employees questioned in the case. Two men – known as the “two Tonys” because they shared first names – were given polygraphs in the middle of the night Sept. 8, about five days after Nathan’s death. Tony Lackey and Tony Dodds were friends. Lackey, in fact, was dating Dodds’ sister, Mary, at the time of Nathan’s death. The two would eventually marry.

While the polygraph results are not in the case file, there’s a summation of one of them that states the administrator believed Lackey was truthful when he said he didn’t know what happened to Nathan.

Mary (Dodds) Lackey was also polygraphed Sept. 8. In a 2020 interview, she said remembers the experience because it was jarring to see several patrol cars pull up to her house around 12:30 a.m. When she looked out a window to see what was happening, she said an officer beckoned her over and told her that “Anthony Lackey needs your help.”

When Mary Lackey learned police were investigating a murder, she said she insisted to them, “My husband ain’t gonna hurt a fly.”

(During his polygraph interview, however, the administrator wrote that Lackey acknowledged having “stomped his ex-girlfriend … causing serious injuries [broken bones] because she kicked him in the groin.” The administrator also wrote that Lackey said he choked a woman and punched her in the forehead in 1993.)

Mary Lackey said that the night before Nathan’s death, she and Tony Lackey stayed at her aunt’s house. While Tony was in and out throughout the night, she remembered him being in bed between 6:30 a.m. until he woke up for good between 9-9:30 a.m.

This contradicts a shuttle driver named Gwyn Dorsey who drove Embassy Suites workers to and from the hotel. Dorsey said he was certain that on the morning of Nathan’s murder, he picked up his usual third-shift passengers, which included both Tony Dodds and Tony Lackey. This stood out because Lackey wasn’t scheduled to work that morning but was there for the shuttle leaving the hotel around 8:35 a.m.

Nathan’s body had been discovered about a half-hour earlier, though Dorsey wasn’t yet aware of the chaos inside the building. Mary Lackey said she had nothing to do with Nathan’s death and was sure her husband and brother didn’t, either.

In an interview for the Accused podcast, assistant prosecutor Mark Piepmeier said that Jones wasn’t the only Embassy Suites worker investigated in the case.

“We looked at anybody that had a passkey,” he said. “I think that was the defense’s case – that there was a lot of other people that could have done it. But no one else had the fight bite. No one else had her jewelry.”

The ‘fight bite’

While prosecutors described Nathan’s pendant as “smoking gun”-level evidence against Jones during his trial, it was the eikenella corrodens infection in Jones’ hand that stuck with juror Esther Geiermann.

“How could he have gotten that bad infection when the only way to get it is a bite on the hand?” Geiermann said in a phone interview. “I don’t see how he could not have been guilty.”

This part of the case gets tricky, as forensic analysis often can. The gist is this: Jones sustained a cut on his hand the same day Rhoda Nathan died. Three days after Nathan’s slaying, Jones’ hand was so inflamed that he went to a clinic, which referred him to Bethesda Hospital’s emergency room.

There, a hand surgeon named John McDonough happened to be working an emergency room rotation. McDonough had previously done research on a type of injury called a closed-fist injury, which is also known as a “fight bite.” Though McDonough had seen fewer than a handful of such injuries himself, he’d later say that he recognized Jones’ cut as a fight bite. When he asked Jones whether he’d punched anyone recently, Jones said no.

But McDonough said that in his experience, not everyone who has punched someone in the face is quick to admit it, so he took detailed photos of the injury that he would later use in talks about fight bites. McDonough also collected samples from Jones’ hand, then ran cultures to identify what type of bacteria was growing inside the infected joint.

In Jones' medical records, the first mention of eikenella corrodens is preceded by the word “probable.” In later references, without explanation, the “probable” is dropped. The test also identified other bacteria in Jones’ cut, including “moderate beta-hemolytic Strep Group A” and “moderate alpha-hemolytic streptococci.”

Those bacteria were dismissed as so commonplace that they took a back seat to eikenella corrodens during the trial, according to then-court Enquirer reporter Kristen DelGuzzi who now serves as opinion editor for USA Today. (She remembers “eikenella” being front and center during the trial because it had the same number of syllables as the chorus to the then-popular song “Macarena,” and reporters covering the trial sometimes swapped the lyrics while looking for levity during witness breaks.)

McDonough, who served as a star witness for the prosecution, told jurors that the only reasonable way for eikenella corrodens to be among the bacteria in Jones’ cut was for Jones to have punched someone in the mouth, transferring the victim's oral bacteria into the assailant's joint fluid.

Later, McDonough would tell the TV show Forensic Files: “To get the eikenella to propagate, you have to break the dental plaque. There has to be significant injury. And that happens when you break a tooth … or if a hard object comes in contact with it, such as a fist or a hand bone.”

Jones’ current lawyer, Barnhart, disagrees, as have microbiology experts consulted by The Enquirer.

“You couldn’t just get eikenella only from fight bites,” said Emily Dault, a senior technologist with the Henry Ford Health System in Michigan. “I’ve worked on the bench doing cultures, and we see it all the time. We see it in people’s mouths, in throat cultures. We see it on different sputum cultures because, not to be gross here but, it all comes up the same tube. So it’s all typically coming out of the oral cavity somehow.”

An expert testified to something similar during Jones’ original trial, but the testimony was presented to the jury as a pre-recorded deposition, meaning that the expert – Dr. Joseph Solomkin, a Harvard University graduate who would later found the World Surgical Infection Society – couldn’t be asked to rebut or expand on any of the questions posed to McDonough.

In a later hearing, Solomkin testified that prosecutors had made “several inaccuracies and misstatements” during Jones’ trial that he could have been able to clarify if he’d testified in person. For example, he took issue with McDonough’s contention that eikenella corrodens was extremely rare.

“It’s not a mysterious or rare organism,” Solomkin said. “We see it frequently and we see it in the range of different infections and the common denominator is contamination from an anaerobic, from material. It doesn’t have to really be human material that is in an anaerobic state.”

He said then, and Dault agreed recently, that it makes sense for a hand surgeon’s exposure to eikenella corrodens be limited to fight bites, but that doesn’t mean dental plaque is the only way the bacteria can enter a hand wound. In fact, Solomkin said, eikenella corrodens can thrive anywhere there’s low oxygen, “including our own mouths and feces and any rotting garbage, anything that has protein and is deprived or has reduced amount of oxygen … It’s well established in the medical literature.”

The other facts

That rundown hit the highlights of evidence presented during the 1995 trial, but Barnhart said there was other evidence omitted that shouldn’t have been. The story, based on affidavits and interviews with various family members, goes like this:

About a year after Nathan’s death, a woman named Delores Suggs spent a short stint in the Hamilton County Jail. While there, she met a woman named Linda Reed, with whom she struck up a when-in-Rome type of friendship. One day, the two were sitting by each other in front of the communal jail television when Reed told Suggs in a hushed voice that her husband had killed a woman at a Blue Ash hotel the previous year and that he had framed a Black man for the crime.

Suggs’ stint was only days long because it stemmed from unpaid court costs, the balance of which she was allowed to pay down by spending voluntary time in jail, so she’d go for a day or two to knock $30 or so off her bill. After she went home, Reed’s story about a man framed for murder bothered Suggs enough that she mentioned it to a church deacon named James Wilson, who urged her to call the police. This was just weeks before Jones’ 1995 trial was set to begin.

In her affidavit, Suggs said that she did call police and reported the conversation, but she said the officer with whom she spoke blew her off. Suggs shrugged off the incident until one night in 2016 when she saw wrongful convictions featured on a nighttime true crime television show. After she watched the episode, she awoke her daughter, Tierria Suggs, who said that her mother was clearly rattled.

“She came in my room and she was so concerned,” Tierria Suggssaid. “She was, like, really serious. It was my first time ever hearing about it, and I was just asking, ‘Why? Why wait so long?’ And she was like, she tried to do it but they told her that the case was closed. She tried to call.”

The younger Suggs sent a message to Jones via JPay, a service through which people can send electronic messages to prisoners. Jones alerted his lawyer, who arranged for Delores Suggs to provide an affidavit.

Linda Reed, the woman who said her husband killed Nathan, died in 2002. Her husband Earl Reed died in 2011. Neither is alive to answer questions about the supposed confession, which Deters has dismissed as inadmissible hearsay.

It’s indeed possible that Suggs’ story of a roundabout confession might never have been allowed before the 1995 jury, especially because there’s documentation suggesting Linda Reed struggled with mental health issues.

Barnhart agreed, but she said that police still had a duty to investigate Delores Suggs’ tip when she called it in before Jones’ trial. She said ignoring the call was a violation of a rule established by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1963 case Brady v. Maryland, in which the court ruled that prosecutors have to turn over to defense lawyers potentially exculpatory evidence favorable to their client.

The accused

If this all seems complicated, that’s because it is. Outside of actual trials, court hearings aren’t often scheduled to span several days, but Jones’ is set for three in late August.

That Jones is alive to mount this final effort at exoneration is an interesting aside here. He was sentenced to die in 1996, after which years of appeals kept his execution off the state's calendar. His first publicized death date was to be in 2015. His next, in 2019.

The Crime: The 1994 murder of Rhoda Nathan and the investigation that followed

Another interesting aside: Rhoda Nathan's death wasn't the first time Cynthia Kirsch's family had been touched by murder. Her husband's grandmother was killed a decade before Nathan's death.

"She was a landlord, and she collected rents. She was 80-something years old," Jeffrey Kirsch said. "One of her tenants knew she had money and forced his way into her apartment."

As with Nathan, the elderly woman was savagely and fatally beaten. The man who was convicted served 14 years in prison.

"That's not quite enough, but I've always been against the death penalty, even for my own grandmother," Jeffrey Kirsch said.

He and his wife lean toward Jones being guilty despite his protestations. But even if he is guilty, they said they wonder if nearly 30 years behind bars has been punishment enough.

Jones, meanwhile, would likely be out of prison if he'd agreed to plead guilty to manslaughter, an offer he refused pretrial. He has repeatedly said he would rather die than admit to something he didn't do.

In recent messages to The Enquirer, Jones said he’s anxious for his upcoming days in court. All he wants, he wrote, is for the truth to be told in a fair hearing.

“The fact is I did nothing wrong,” he wrote.

Police and prosecutors don't believe him.

The real question is: Even if he were telling the truth, if all the dubious evidence could be reevaluated, if his arrest was rushed and his sentence racially motivated, would anyone listen or would they figure that his conviction is proof enough that no one erred?

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: 'Accused' true-crime podcast: Death-row inmate's bid for new trial