Don’t call it summer school. It’s ‘camp’ this year — and many students are here for it

Summer break is on hold for thousands of North Carolina students as they try to make up for learning lost during the pandemic and to prepare for next school year.

Typically, only a fraction of the state’s 1.5 million public school students attend summer school. But record numbers are attending this summer under an expanded six-week program required by the state to help students deal with how COVID-19 disrupted learning for the past 15 months.

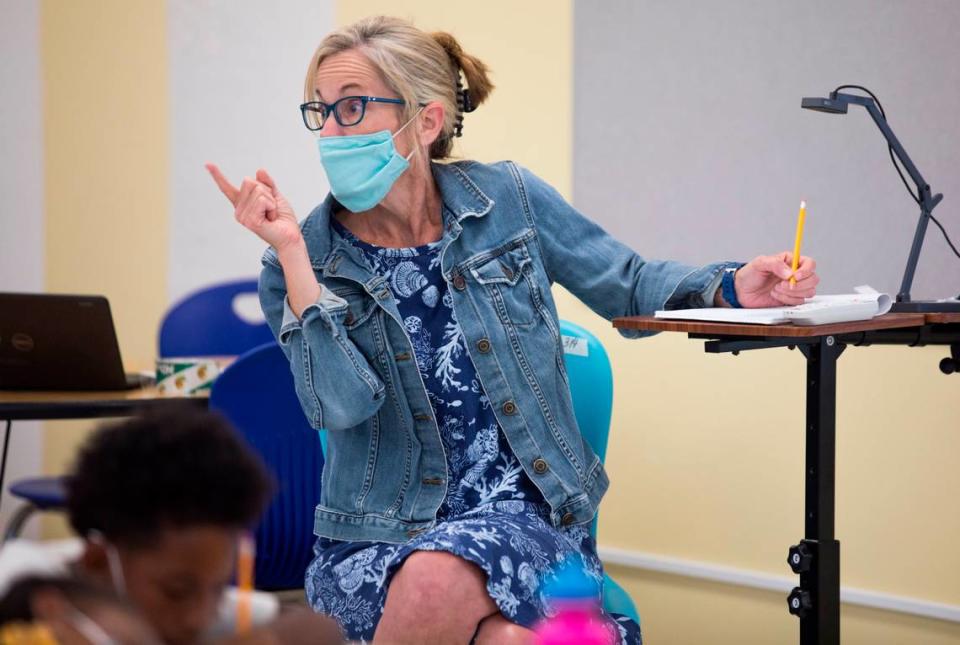

Teachers are hoping to maintain the interest of students who might prefer not to be in school over the summer.

“We’re trying to approach learning this summer from like a camp perspective,” said Tyler Steketee, site coordinator of the summer program based at Eno Valley Elementary School in Durham. “I don’t want to say it’s more exciting, because I think we do a good job of making learning exciting during the school year.

“But it’s something different than what we traditionally do.”

Schools invite students to attend ‘camp’

The General Assembly passed the “Summer Learning Choice for NC Families” bill requiring school districts to offer students at all grade levels at least 150 hours or 30 days of summer in-person instruction, along with enrichment activities such as sports, music and arts.

The program is geared toward at-risk students, but attendance is voluntary and is open to any student, space permitting. For instance, Durham Public Schools is offering the Hub Farm Summer Camp to provide hands-on learning opportunities for K-2 students who aren’t behind academically.

But most students attending this summer are classified as being “at risk.”

Schools are calling their summer programs “camps” to help show learning will be different. In Wake County, the program is “Camp WCPSS.” Durham’s programs are named based on the schools they’re located at, such as “Camp Eno Valley.”

Camp WCPSS includes activities such as themed days, animal wax museums and science labs.

“We feel like we’re in a good place in terms of making the program come alive for our students that we want to serve,” Brian Pittman, Wake’s senior director of high school programs, told the school board last week.

In Durham, teachers are offering science-based thematic units. For instance, Camp Eno Valley’s autistic students are trying to grow lima beans and third-grade students made a diorama of life cycles of frogs.

Steketee said the dance teacher at Camp Eno Valley adapted her lessons to do a lot of hip hop because so many boys were interested.

Providing social-emotional learning

But Wake and Durham also say they’re taking time this summer to work on building the “social-emotional skills” of students that they may have missed while learning remotely. This includes helping students build emotional management strategies and social skills such as controlling their emotions.

“We had a lot of kids that didn’t do well,” said Casey Watson, a Durham Public Schools spokeswoman. “That’s across all schools. They just struggled at home trying to do remote, especially in this (elementary school) age range, and so we’ve tried to put extra emphasis on helping kids have a safe space to talk about their feelings.”

Many students across the state and nation struggled during the extended period of receiving only limited amounts of in-person instruction.

Schools have reported increases in the number of students who are failing classes and not showing up regularly.

Test results showed that the majority of high school students did not pass state end-of-course exams given in the fall. In addition, earlier in the year school districts reported that 23% of their students are at risk of academic failure.

School leaders say they’re hoping the summer learning will help get students ready for next school year. For instance, Wake is having rising sixth-grade students and rising 9th-grade students attend summer programs at their new schools to help them make the transition.

“We are excited at this point to really launch the program and know that it’s going to create a strong foundation and really some positives for our students who we believe will enjoy the program,” Pittman said.

Record enrollment expected this summer

Pre-pandemic, the only students who typically attended summer school were 1st-grade, 2nd-grade and 3rd-grade students who were having trouble reading. In 2019, 28,171 students attended Read To Achieve summer camps.

The final statewide figures for this year’s expanded summer learning program aren’t in yet, but they’ll dwarf prior years.

In Wake County alone, more than 19,000 K-12 students are attending summer programs. In 2019, 2,189 Wake students attended summer school.

“We all are excited about the opportunity and potential for this summer,” said Wake County school board chairman Keith Sutton.

In Durham, 9,000 students are attending summer programs, compared to the 900 to 1,000 who attended in prior years.

Johnston County has 10,067 students attending summer school. Chapel Hill-Carrboro has more than 2,100 students, and Chatham County has more than 2,000 students attending.

Offering higher pay, bonuses to teachers

Initially there were concerns that schools would be able to find enough teachers to work in the summer program. But Triangle school districts are reporting that they’ve filled most, if not all, of their vacancies now that the summer programs are in session.

To entice teachers, lawmakers required school districts to offer teachers at least a $1,200 bonus for working in the program. But districts added other incentives, including a $2,000 bonus that Chatham County offered to special-education teachers.

Wake County is offering teachers $45 an hour and an additional bonus of up to $1,200 if they work the entire six-week program.

Durham is offering teachers $40 an hour. Steketee, who runs the program at Eno Valley Elementary, said teachers have been selfless and are doing whatever it takes to help students learn this summer.

“The great thing about DPS teachers is they are committed to student success, and that’s why I don’t feel like we had the staffing issues that maybe some other counties have had,” Steketee said.