DeSantis proposes congressional map that dilutes minority voting strength

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

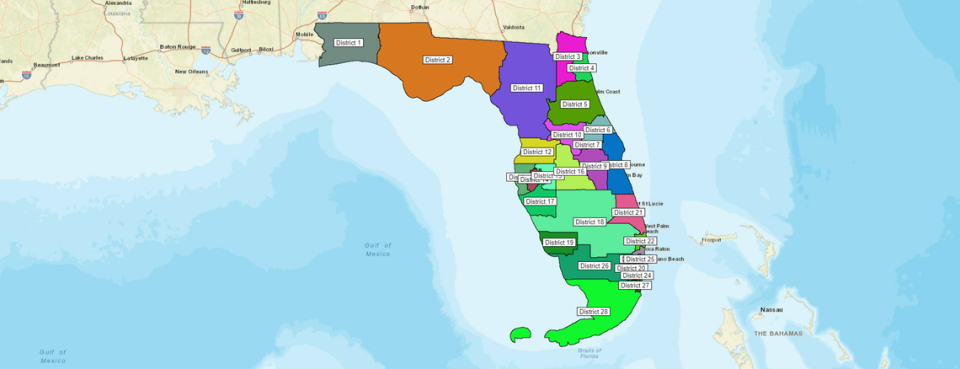

Breaking with tradition, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis inserted himself directly into the redistricting fight by submitting a map that experts say would reduce Black and Hispanic voting strength in congressional districts and raise new questions about his commitment to the Fair District standards of the Florida Constitution.

The map, posted to the Florida Redistricting website on Sunday by DeSantis’ general counsel, Ryan Newman, would create five districts that are at 50% Hispanic voting-age population, but experts say that may not be enough to elect Hispanic candidates in districts with high numbers of voting-age Hispanic non-citizens.

The map would also reduce the number of Black-majority districts in Florida from four to two, eliminating Black districts in North Florida and Orlando and leaving two in South Florida.

Those changes came under fire by Democrats and voting advocacy organizations who said they violate both the provisions of the federal Voting Rights Act and the Fair Districts provisions of the Florida Constitution, which bar lawmakers from adopting maps that reduce minority voting strength.

“In stark contrast to the Senate maps, whoever drew these maps seems to have totally disregarded the Fair Districts provisions of the Florida Constitution and federal law,’’ said Ellen Freidin, president of Fair Districts Now, the advocacy organization formed to monitor the implementation of the Fair Districts amendments.

“This map dilutes the power of minority voters,’’ she said. “It reduces the number of districts in which African Americans could elect a representative of their choice by 50%, and reduces voting power of Hispanic citizens despite the dramatic growth of the Hispanic population in Florida over the last 10 years. In addition, the map appears to have been drawn intentionally to favor Republicans.”

Cecile Scoon, president of the League of Women Voters of Florida, which was among the plaintiffs that successfully challenged the congressional and state Senate maps in the 2010 redistricting cycle, said the governor’s map raises concerns.

“A preliminary review of the governor’s redistricting plan for congressional maps seems to give inadequate adherence to the Fair Districts created by Floridian Citizen Initiative in 2010 and the VRA [Voting Rights Act] of 1965,’’ she said in a statement.

The logic behind governor’s map

The governor’s office did not immediately respond to requests for comment, but Newman said over the weekend that the administration has “legal concerns with the congressional redistricting maps under consideration in the Legislature.” He did not elaborate on his concerns.

“We have submitted an alternative proposal, which we can support, that adheres to federal and state requirements and addresses our legal concerns, while working to increase district compactness, minimize county splits where feasible, and protect minority voting populations,’’ he said, according to a statement published in Florida Politics. “Because the governor must approve any congressional map passed by the Legislature, we wanted to provide our proposal as soon as possible and in a transparent manner.”

The governor’s proposed map creates five Hispanic-majority districts, leaving one district in Orlando but adding a fourth district in South Florida, which currently has three.

The current Congressional District 25, now a Hispanic-majority district represented by Republican Mario Diaz-Balart, would lose its Hispanic-majority characteristics and become Congressional District 26, stretching from Hialeah to Collier County. While the proposal is about 21% Hispanic voting-age population, it is 61% non-Hispanic white.

The proposal also changes the composition of current Congressional District 20, the Black-majority district previously represented by the late Democratic Congressman Alcee Hastings. Much of that district would become the new Hispanic district with a voting-age population of about 50%, diluting the influence of the remaining Black voters, who comprise 15% of the district.

The DeSantis map would also convert Black-majority districts in North and Central Florida into non-majority districts, leaving only two Black-majority districts, proposed as Congressional District 24 and Congressional District 23. CD 24 would have just over 46% Black voting-age population but also would have 43% Hispanic voting-age population. CD 23 would have 43% Black voting-age population and 24% Hispanic voting-age population. Both would have elected President Joe Biden in 2020 with more than 70% of the vote.

The partisan breakdown of the map would give Republicans an advantage of 18 to 10, including the new district Florida acquires because of population growth. The current partisan breakdown is 16 to 11.

By contrast, the map the Senate Reapportionment Committee approved last week on a 10-2 bipartisan vote, leaves the Republican advantage where it is today. Under the Senate plan, if the 2020 elections were held today, 16 districts would have voted for former President Donald Trump and 12 would have voted for Biden. Two Miami-based districts, Congressional Districts 26 and 27, are considered virtual toss-ups and could lean Democratic or Republican.

U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, a Tallahassee Democrat who represents the Black-majority district that was first drawn with the support of Republicans in 1992, told the Tallahassee Democrat on Tuesday that the governor’s plan would wipe out Black access in the region.

“I don’t know why the governor wants to pick a fight with me,” he said, noting that the plan came out on the Martin Luther King holiday weekend. “In all my years in government I’ve never seen the governor’s office submit a map before.”

Unlike the Senate, the governor’s map takes an approach similar to one taken by legislators in Texas, where they drew white majority congressional districts in places previously represented by minorities, including in regions with Hispanic and Black minority growth. The map is now being challenged by the U.S. Department of Justice for violating the Voting Rights Act.

“It does have a very similar feel to those Texas maps that came out,’’ said state Rep. Evan Jenne, D-Dania Beach, in response to a reporter’s question. “I think probably that’s where this is coming from.”

Redistricting is a highly politicized process

Every 10 years legislators are required to revise the state’s political boundaries for legislative and congressional districts to accommodate changes in population and ensure that every citizen is fairly represented.

Because the political stakes are very high, every map has been subject to intensive litigation and, in every redistricting cycle since the 1990s, courts have concluded that because there are many Hispanics in Florida who are not registered voters, a district must have more than 50% Hispanic voting-age population to effectively elect an Hispanic to office.

There are traditionally two approaches partisans have taken to map drawing. One is to draw a favorable district as conservatively as possible to avoid litigation and the other is to maximize representation and take chances in court.

The Senate congressional map, which had been praised by Democrats as fair and reasonable, however was criticized by Republicans.

Steve Bannon, the former Donald Trump chief strategist, posted the governor’s phone number on his Gettr account on Friday with an appeal.

“We need five more MAGA seats in Florida,’’ he wrote. “Contact Ron DeSantis’ office and tell him to sty focused on redistricting in his state to be sure MAGA gets these seats.”

Matt Isbell, a redistricting expert working with Democrats, called the governor’s map “a stunt.”

“DeSantis wants to appear he’s still the MAGA boy, so he’s proposed a map that is purposely ridiculous — namely destroying minority seats. So this is just a stunt,’’ he said in a post on Twitter. “Feel free to obsess over it. But I recommend ignoring.”

Unlike the legislative maps, the governor has veto power over the congressional map, and this is the first time in Florida history a Florida governor has publicly proposed a congressional redistricting map, experts said.

DeSantis, who has used his three years in office to advance a vigorously partisan agenda and to upset the norms of the office, is also the only governor who served for four years in Congress before being elected as the state’s chief executive.

But it became clear on Tuesday that the Senate, which is scheduled to vote out its proposed map as early as Wednesday, may not be ready to budge from its plan. The Senate had set a 2 p.m. deadline for any amendments to its maps and by the deadline no one had submitted the governor’s map.

“We are confident in the constitutionality of the maps passed by the Senate Committee on Reapportionment,’’ Sen. Ray Rodrigues, chair of the Senate Reapportionment Committee, said in a statement to the Herald/Times. “Questions about the governor’s position on the maps should be directed to the Governor’s Office.”

House Redistricting Chair, Rep. Tom Leek, R-Ormond Beach, told the Herald/Times late Tuesday that the governor’s map is being reviewed and would not answer whether or not it will be incorporated into the House’s proposals when the committee meets again. A meeting of the Subcommittee on Congressional Redistricting that was scheduled for Thursday was canceled on Tuesday.

Leek also said that the House had not been notified why the governor’s office has “legal problems” with the current legislative maps and directed questions to the governor’s office. The governor’s press secretary, Christina Pushaw, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Unlike many Democrats, Scoon of the League of Women Voters of Florida, criticized the Senate’s congressional and state Senate maps, saying they do not go far enough to protect minority voting strength.

“It is undeniable that Florida’s minority population has grown since the creation of the current maps in 2016, which used data from the 2010 Census,” she said in a statement. “At this time, it does not appear as if the Senate has explored the possibility that additional minority districts could be created with data from the 2020 Census. The proper steps must be taken before new district lines are approved to ensure that African American and Hispanic voters are fairly represented in the political process.”

Mary Ellen Klas: meklas@miamiherald.com, @MaryEllenKlas