How the department store fell out of fashion

This January I took my 12-year-old daughter to Oxford Street in search of relics. I wanted to show her – before it was too late – how we used to shop.

“Can’t we go to Primark?”

No Primark. No H&M or Zara. Instead we’d be starting at Selfridges, still a benchmark for that almost extinct species: the department store. My daughter had never heard of it. “Mr Selfridge was an American,” I began. “He thought London’s department stores were incredibly fusty and old-fashioned. He wanted to shake things up.”

It was Harry Gordon Selfridge who came up with the slogan “Only XX more shopping days ’til Christmas!”; Selfridge who put perfume by the entrance doors to pull the punters in (and conceal the smell of horse manure); Selfridge who banned the demeaning term “shop girl”, preferring to call his armies of female staff “shop assistants”. Selfridge also introduced a ladies’ lavatory, the first in any department store. In this small but significant way, he promoted women’s emancipation.

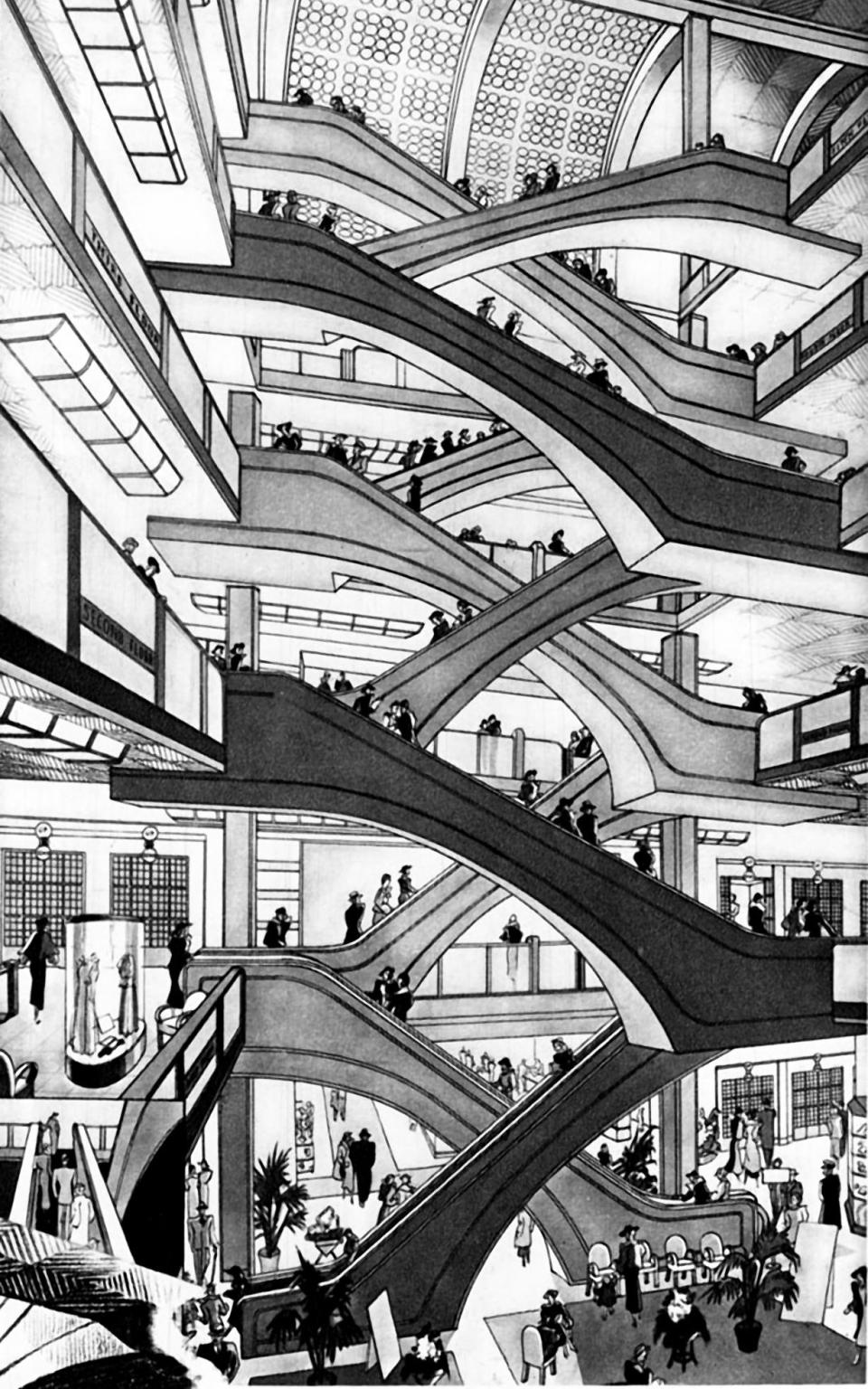

We rode the escalators up, past outrageous outfits on transparent dummies, past oligarchs and Arab princes trying on bejewelled trainers, right up to a real skatepark and shredded designer wear. My daughter’s eyes were on stalks. This was cool. Exciting even, like the best kind of interactive museum. “A social centre, not a shop” was the slogan at the great store’s opening in 1909. Selfridges has survived today by cleverly pivoting back to the Golden Age of retail, a time of spectacle, glamour and – crucially – participation. Its original white pillars and moulded ceilings are on display once again, but it feels fresh, not like some relic of the past.

Back outside, the vibe was less buoyant. Footfall on Oxford Street has fallen by 70 per cent in the past two years; many household names have closed (Debenhams, House of Fraser, Top Shop).

“Look up!” I kept saying, as my daughter’s eyes locked onto yet another lurid American Candy store. “Look for the really big buildings. That was once Bourne & Hollingsworth.”

“Mum. It’s a Next.”

“It didn’t used to be. It’s Art Deco. Mid-Twenties. Your grandparents used to meet beneath that clock. Look up.”

We stopped outside House of Fraser and its “Closing Down Sale” signs. By the end of the week, this once supremely confident emporium would close its doors for good. In the interests of education, I propelled my daughter inside.

We’ve lost an astonishing 83 per cent of British department stores in the past six years. Some 237 buildings currently sit empty and purposeless, evidence of the seismic shift in our shopping habits. It’s hard to believe that cherished independents such as Jenners of Edinburgh, founded 1838, and Boswells of Oxford, trading since 1738, have shut their doors for good. When the pandemic began to pick off our remaining big stores, it seemed to me like a pivotal moment in history: a moment to take stock of the fast-disappearing past. We’re losing them as physical places, but we’re also losing their narratives – witness the vast Debenhams archive, currently in emergency storage with no public access, its fate uncertain.

Once I began to scratch the surface, I couldn’t stop – eventually piecing together the stories of 50 “lost” department stores across greater London – from Bodgers of Ilford to Barbers of Fulham, from Marshall & Snelgrove to Derry & Toms. I was hooked by these flamboyant tales of rampant ambition, thrusting architecture, female shoplifters and put-upon workers. Most entertaining were the stories from the suburbs – the staff garden behind Pratts of Streatham; the first Christmas Grotto at J. R. Roberts of Stratford in 1888; the showmanship of Chiesman’s of Lewisham, pulling in crowds with an “untameable lion” called Vixen in 1931.

Mothers and daughters have been visiting department stores since the Victorian era – for school uniforms, for wedding gifts, prams, perms and (most importantly) tea. “Do you ever happen to recollect the dark, sad days when you had not heard of the Dickins and Jones Tea-room?” writes ‘Olivia’, author of a “Prejudiced Guide” to the London shops, 1906. “I can never forget their shining coffee kettles, nor the quality of their tea. You may buy it by the pound after you have tried it. I generally do, after a cup there.”

Today there was no tea to be had at House of Fraser: a crack team was in the process of packing up the entire store. Before 2001 it was D. H. Evans, founded in 1878 by a Welsh draper named Dan. When Harrods acquired the business in 1928, the management decided to create “London’s Most Modern Shop”. It was time to dent Mr Selfridge’s breezy domination of Oxford Street.

The new D. H. Evans was a statement building: steel frame, concrete floors, German Art Deco in style. It rose one hundred feet – higher than anything else on Oxford Street. At its unveiling in 1937, the year of King George VI’s Coronation, the fifth floor restaurant was the place from which to watch the procession. On the fourth floor was a hair and beauty department with “padded comfort chairs, spring rests for the feet, a telephone, and sterilising cabinets”. My mother still remembers the absolute thrill of that soaring escalator hall, transporting her up to consumer heaven in the lean, post-war years.

Nothing remains from this era, but as we rode the escalators upwards we could just about make out the “modernistic” plasterwork on the ceiling, all part of Louis David Blanc’s original design. Will the remaining Deco features survive the £100m revamp by Publica Property Establishment, the company converting the building to mixed-use space with a top floor restaurant, and “winter gardens” for office workers? As department stores pass into history as a now-defunct type of social architecture, it’s heartening to discover that many “lost” buildings are now getting sensitive and imaginative makeovers rather than the wrecking ball.

“A top floor restaurant?” my daughter considered, craning her neck upwards from pavement level. “That’d be pretty cool. You could see the whole of Oxford Street from up there. Everything from Selfridges to Primark.”

Three new uses for London department stores

Arding & Hobbs of Clapham Junction

Something of a test case in the repurposing of department stores, a “sensitive” transformation by property specialists W.RE is currently taking this former Debenhams back to its 1920s Baroque glory, exposing original features and stripping out the travesties of 1960s and 70s refurbs to create new retail, leisure and office space. There is, however, consternation in Battersea about the modernist new rooftop extension which changes the skyline.

Randalls of Uxbridge

The family store of Sir John Randall, MP, closed in 2015 after 123 years of trading. It faced demolition – but thanks to enlightened local planning, this near perfect 1930s time capsule has been saved, restored and is now the groovy period face of a block of contemporary apartments. Original elements from the interiors have been retained in an attempt to “respectfully pay homage to the history of the building” – now renamed Gatsby House.

Holdrons of Peckham

Once the jewel of Peckham Rye, this unloved T. P. Bennett building from 1935 has been nurtured back to life by Afghani immigrant, Akbar Khan. Known to all as Khan’s Bargains, Khan has embraced the building’s history by personally ripping out false ceilings to reveal its secrets – such as a spectacular Art Deco vaulted lightwell made of “Lenscrete”. The yellow paint is to be removed from the white faience tiles and the Art Deco windows fixed. A renaissance is taking place on Rye Lane.

London’s Lost Department Stores by Tessa Boase (Safe Haven Books, £16.99)