Democrats push long-shot reform bill that stops short of defunding police

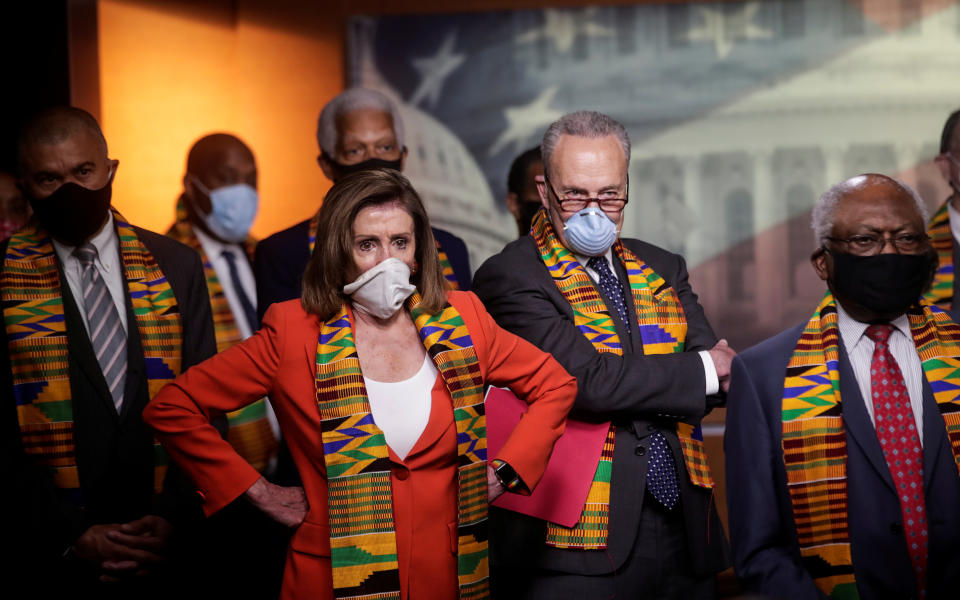

WASHINGTON — Promising to eradicate what Rep. Hakeem Jeffries of New York called a “malignant tumor of police brutality,” Democrats from both congressional chambers announced that they would soon introduce legislation to significantly reform law enforcement practices.

That legislation, however, appears to fall far short of demands activists have made in recent days, thus further imperiling the bill’s challenging-to-begin-with prospects for passage into law.

Titled the Justice in Policing Act, the new legislation is being proposed in response to the killing of George Floyd, an unarmed 46-year-old black man, by members of the Minneapolis Police Department two weeks ago. Protests against police brutality and systemic racism have roiled the country for the past 10 days.

Polls show those protests are supported by most Americans. Less clear is just how much law enforcement reform Americans — or their representatives in Washington — are eager to see enshrined into law.

“The martyrdom of George Floyd,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Monday at a press conference on Capitol Hill, “has made a change in the world.” As she and other Democrats spoke, funeral services for Floyd were beginning in Houston. Floyd’s brother Philonese could testify later this week in a House Judiciary Committee hearing on discriminatory policing, one of several hearings Democrats are expected to hold on policing in the coming weeks.

The new legislation appears to be at least partly based on a report published in 2015 by the Obama administration on how policing can adapt to a rapidly changing society. Although the text of the legislation had not been made public at the time this article was published, Democrats at Monday’s press conference described policy proposals including national use-of-force standards for police officers, a countrywide registry of police misconduct, the creation of independent bodies to investigate such misconduct and a reversal of the militarization of police forces around the nation.

“We have confused having safe communities with hiring more cops on the street,” said Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., arguing that collective well-being, including public safety, would be better achieved through investments in community social services.

Some in the party have proposed that city and state governments should divert money from law enforcement budgets to fund other programs, and such decisions would fall mostly outside the reach of Washington’s lawmakers. But the federal government does have some say as well.

Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., who chairs the Congressional Black Caucus and is introducing the new legislation, said on Monday morning that in addition to putting new restrictions on policing, the bill would include funding incentives for “communities to have projects that begin to re-envision what policing might be about” by bolstering mental health and other services that have been steadily eroded over the years.

Bass represents a part of Los Angeles that in 1992 broke out in unrest after four white officers were acquitted in the savage beating of black motorist Rodney King that had been caught on camera by a bystander. Bass was a community leader at the time and participated in protests. She has compared the King case to the Floyd killing.

While Democrats seem bolstered by the national response to Floyd’s death, the Justice in Policing Act faces a fraught legislative journey. Even if it passes both the House and Senate, it would need the signature of President Trump, who has cast himself as a friend of law enforcement and has praised “rough” policing measures.

The bill also removes some of the legal protections police officers now enjoy for engaging in unjustified roughness. Such protections, known as qualified immunity, shield law enforcement officials from being held personally liable for actions undertaken in the line of duty.

Jeffries, who chairs the House Democratic caucus, said that the kind of knee-on-the-neck maneuver that Police Officer Derek Chauvin used to kill a handcuffed and prostrate Floyd would also be banned by the legislation. Such a ban would apply only to federal law enforcement entities, not to the state and local police forces that make up the overwhelming majority of the nation’s 18,000 police departments. Federal law enforcement officers would also have to wear body cameras.

Pelosi said the bill would, in addition, make the kind of racialized mob violence known as lynching a federal hate crime. An anti-lynching bill has been widely endorsed by members of both parties but is currently being held up by Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky. Last week, Paul lectured Harris and others on the Senate floor on the shortcomings of the anti-lynching bill, drawing an impassioned response from Harris.

With some progressives calling for an outright abolition of police departments, and others favoring cuts to law enforcement funding, the Democratic bill is unlikely to satisfy activists affiliated with Black Lives Matter and other groups. Seemingly aware of such criticism, Pelosi called the bill “transformative” and “not incremental.”

Passing legislation in a Republican-controlled Senate has been exceptionally difficult for Democrats since they took control of the lower chamber in the 2018 midterm elections, and the contentious issue of police reform is unlikely to be an exception. Aware of the challenges that await, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., promised that Democrats would “fight like hell” to pass the legislation, likely by appealing to Republicans like Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, who have shown solidarity with the protests.

“Democrats will not let this go away,” Schumer promised Monday. Like all other legislators who spoke, Schumer had his shoulders draped in a patterned African scarf known as a kente cloth.

Republicans, meanwhile, have been eager to paint all efforts at police reform as an endorsement of lawlessness, despite the fact that no leading Democrat has called for actually abolishing police departments. In an echo of the tactics Richard Nixon used successfully in 1968, Trump sees appeals to law and order as crucial to his reelection chances. But unlike Nixon, who was running against nearly eight years of Democratic rule, Trump is an incumbent, which frustrates his capacity to make that argument.

Between the expected intransigence of Senate Republicans, the long-standing efforts of some on the right to portray liberals as soft on crime and the growing demands from progressives to fundamentally rethink policing, congressional Democrats face long odds on the police reform bill.

Despite that, Democratic leaders attempted to project confidence on Monday morning.

“This is a first step,” Pelosi said. “There is more to come.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: