As COVID fades, Americans are returning to beach towns. But restaurants and stores are struggling with shortages

BETHANY BEACH, Del. – The great American beach town – and its throngs of summer visitors – is back.

Beach workers? Products?

Not so much.

Americans are streaming to U.S. beaches with a vengeance this season, eager to make up for a pandemic-marred 2020 that left shops and restaurants struggling to survive amid strict capacity limits and fewer customers. But while merchants and restaurateurs are happy their patrons are back in force, they’re scrambling to serve them with fewer employees and products.

The reopening economy has intensified nationwide labor shortages and supply chain bottlenecks that are forcing beach-area business owners to limit their hours, substitute popular offerings with the next best thing, and absorb sharp price increases that they’re at least partly passing on to customers.

Occupancy at Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, hotels reached 86% on a recent weekend, up from 76% during a comparable weekend last year and 80% in 2019, according to the Rehoboth-Dewey Beach Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Center.

While celebrating the rebound, chamber president Carol Everhart adds, “We have a major problem. We have no staff.”

Since Memorial Day, Nicola Pizza, an iconic blonde wood-paneled restaurant a block from Rehoboth Beach, has notched sales that are running above the same period last year but somewhat below 2019 levels because the eatery has had to curtail its hours.

“I don’t have the help,” says co-owner Nick Caggiano Jr., whose father founded the restaurant in 1971 and added a second outlet next door in 2010. He has 64 workers but could use about 90, a gap that has lengthened typical waits for dinner from about 20 minutes to a half-hour.

Although business owners across the country are grappling with similar constraints, the snags are amplified in beach towns, which generate the bulk of their revenue from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

By September, both the labor crunch and delivery snarls should ease as enhanced unemployment benefits – which may discourage some recipients from taking jobs – run out and more schools reopen. That would, for example, allow factory workers and truck drivers who are caring for remote-learning kids return to work. But by then, the big resurgence from the COVID-19 slump will largely be history in beach towns.

In Bethany Beach, about 13 miles from Rehoboth, last summer’s ubiquitous signs warning beachgoers to wear face masks have been replaced by more subtle reminders to “use the beach responsibly.” Along the quaint, two-block hodgepodge of shops and restaurants off the beach, smatterings of face-covered visitors have given way to steady flows of maskless revelers, even on a recent 70-degree, partly cloudy Saturday.

Gone are shop window posters with lists of health-related entry requirements. In their place: Almost-pleading "Help Wanted" signs offering $12 or $13 an hour, or more. And with worker shortages triggering longer waits and more customer complaints, some merchants are taking pains to protect the workers they have.

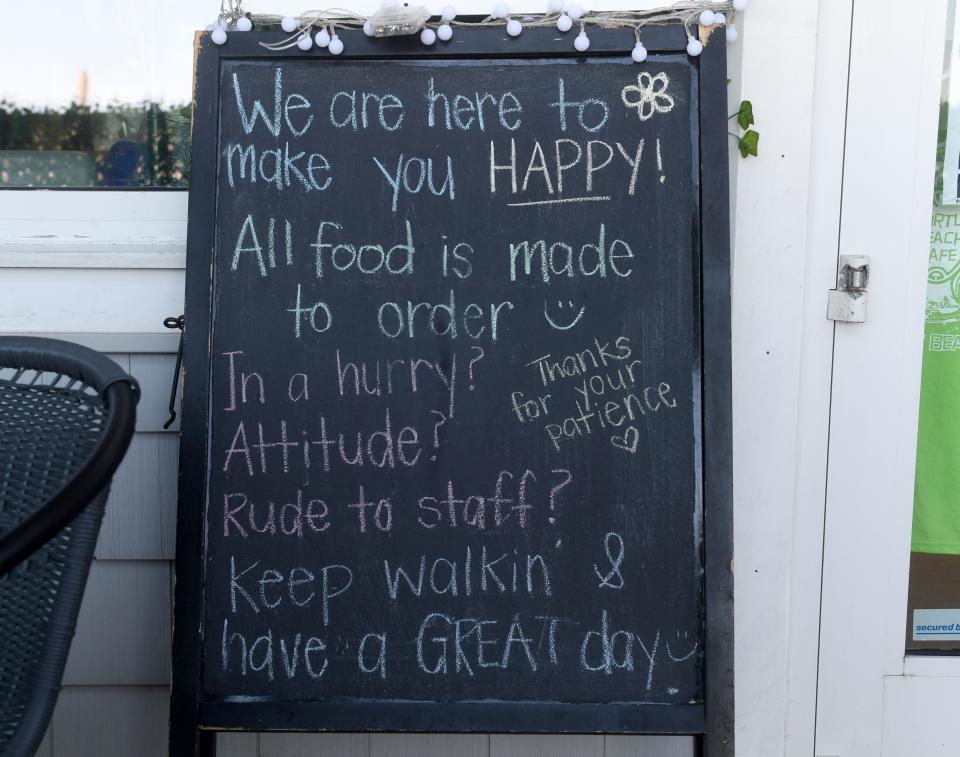

“All food is made to order,” reads the chalkboard sign in front of the Turtle Beach Café on the boardwalk. “In a hurry? Attitude? Rude to staff? Keep walkin’ & have a GREAT day 😊.”

“I can afford to lose (customers) more than I can afford to lose” workers, says café owner Tony Smyth, gesturing to the clutch of hustling employees behind the counter.

‘It’s really devastating us’: Beach towns fear they won’t survive a summer of COVID-19

Busier than ever

The airy Bethany Beach Ocean Suites, a Marriott property, “is definitely busier than any year we’ve seen,” says General Manager Lorrie Miller. But she only has two-thirds of the 60 workers she needs, making guests wait longer for some services and eliciting complaints from those who expect five-star treatment for a weekend rate of about $800.

Miller has bumped up the starting wage by $1 to $14 and offered $1,000 to workers who stay through September, but, “No one is applying for the jobs,” she says.

Linens, meanwhile, are in short supply, requiring a bare-bones staff to do laundry more frequently, and pool towels sometimes run out, forcing the hotel to substitute bath towels, Miller says. Recently, apple juice wasn’t delivered, so hotel staffers rounded up containers at a grocery store and served them to guests in pitchers instead of dispensers at the breakfast bar.

At the Tropicana T-shirt and surf shop on the boardwalk, owner Eric Efergan has just seven summer employees, down from his usual 12. He placed a job posting in a local newspaper but, “I didn’t get any calls – nothing. So I just stopped it,” Efergan says.

He raised his hourly wage to $12 from $10.50. And if employees stay until the end of the season, he’ll throw in an extra dollar for every hour they clocked. But to little avail. He says he still can’t compete with the likes of McDonald’s, which pays as much as $17 hourly.

“I’m a small business,” says Efergan, who also owns the nearby Bethany Beach Hut shop.

As a result, Efergan, an easygoing 48-year-old clad in a V-neck undershirt, jeans and sneakers, is toiling full days and often manning the register. In previous years, he popped in for two or three hours a day just to ensure things were running smoothly.

‘Send me everything’

His bigger problem is inventory. T-shirts, shorts and other items are taking eight weeks to arrive from China after he places an order, up from a normal two weeks. So instead of waiting for his stock to run low before ordering, Efergan told his vendor, “Send me everything.”

He requested 400 T-shirts, up from his standard 60. “If I don’t have a good season, I’ll eat the shirts,” he says.

Even so, there were only a couple of T-shirts and just one baseball cap left in some styles and colors.

“If I don’t have something, I missed a sale,” he says.

With his main vendor depleted, Efergan regularly calls around to alternative suppliers in a scramble to replenish supplies.

Since the global supply network is clogged, freight costs have soared, pushing up prices, especially for larger items that take up more space in shipping containers. Efergan is paying $15 for a beach chair, up from $8, leading him to raise the retail price from $20 to $30.

Customers aren’t grumbling. “They know everything is more expensive,” he says.

Alison Schuch, owner of Fells Point Surf, a clothing boutique, also has been hit with freight price hikes but can‘t pass them on to shoppers because she has to charge the manufacturer’s suggested retail price by contract. That squeezes her profits.

Last week, she received several items that were supposed to arrive in March. “That can be a problem,” she says, noting that she may miss the sweet spot of the season. Some fashion brands are out of stock, forcing her to buy alternatives and work harder to create an inviting customer experience with colors, displays, music and even scents, she says.

“I’m spending a lot more time” hunting for suppliers, Schuch says. Almost nightly, she’s online into the wee hours scouring for vendors as her husband tries to sleep.

At Tidepool Toys & Games, sales are up 80% over 2019, says owner Sandy Smyth, Tony's brother. But he’s not getting small pools and received only 180 boxes of a popular plastic sand shovel with a wooden handle, down from his normal 700. So he turned to a supplier of metal shovels that retail for twice as much at about $10.

Restaurants hit harder

Restaurants are more hard-pressed. At Shore Break on the boardwalk, sales are up about 50% versus COVID-19-tainted 2020 and ahead of 2019’s brisk pace, says owner Kyle McCabe. But he was out of his regular chicken tenders three weeks ago when his supplier ran low, forcing McCabe to buy flour and breading at the grocery store and make his own. He now orders 14 to 16 cases instead of two and stocks up on other popular dishes, such as fennel fries, stashing them in an armada of 12 freezers.

"You have to stay on top of things," says McCabe, whose eatery has a takeout window and some outdoor seating.

His chicken costs have jumped 50% to 60% while crab is up about 20%. McCabe, in turn, has increased his retail prices by 15% to 20%. Customers “don’t even question it,” he says.

Fortunately, he hasn’t had much trouble hiring – he’s staffed up with about 25 employees – but that’s because he brings on young high school kids whom other employers don’t target.

“I try to hire all 14-year-olds and give them short shifts,” he says, noting he enlists extra employees, knowing some won’t pan out. As a result, he spends more time training, putting in 12-hour days and recruiting his wife to help.

Mango’s, a festive, sprawling, restaurant on the beach, is having a tougher time filling out a larger staff. Co-owner Alex Heidenberger says sales are up at least 50% compared with 2019 but he only has about 75 of the 100 workers he needs.

Besides relying on traditional hiring techniques, Heidenberger has cultivated a no-nonsense approach. “I will walk up to someone on the street and say, ‘Hey, you looking for a job?’”

Although food costs have risen sharply – scallops are up from about $13.50 a pound last year to $38 – Heidenberger says he has held the line on retail prices.

“I’m not going to change menu prices every week,” he says. Instead, he serves somewhat smaller portions and works tirelessly on efficiency. It shouldn’t take a bartender more than 10 seconds to make a drink, he says.

With suppliers rationing, he aims high to avoid shortages. If he needs 40 cases of beer, he’ll order 80 and hope to get 20 to 40. “It’s a nightmare,” he says.

Worsening Bethany’s labor crunch is a housing shortage that leaves job candidates from other areas few places to stay even if they accept a job offer, says Lauren Weaver, executive director of the Bethany-Fenwick Chamber of Commerce. Many summer homeowners and renters stayed in units year-round because they could work remotely during the pandemic, she says.

Long lines

Back in Rehoboth's larger, square-mile shopping district, Thrasher's French Fries has struggled to attract college students in part because inexpensive seasonal house rentals are no longer widely available, says general manager Dean Shuttleworth. Like other area businesses, the chain also has brought on fewer foreign J-1 (exchange) students than in previous years because U.S. embassies overseas are conducting only limited interviews due to lockdowns.

Shuttleworth has boosted his hourly wage to $13 from $12 and added a $1.50 summer bonus. Still, he has hired only about 44 of the 60 employees he needs, forcing him to temporarily close one of the three Thrasher’s outlets near the beach.

As a result, the eatery's takeout counter on Rehoboth Avenue draws a fairly steady line that stretched halfway across the wide boulevard on a recent Saturday as large crowds sauntered by.

“Everything takes longer,” says Holly Lyle, 52, as she and three friends sipped dirty martinis at a restaurant bar. The group, who live in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, waited 15 minutes just to be seated for breakfast that morning and their Mexican dinners the previous night were slow to arrive. After dinner, they wanted to hang out at the bar but no dice – no bartender was available.

Later, they sought out another vacation ritual – downing some eggs at a 24-hour diner – but it had shut down early due to staffing shortages.

Yet the group is having a blast and was thrilled to hear live music at a bar for the first time since before the pandemic.

“We will take any little bit we can get,” says Lyle’s friend, Stephanie Erney, 44.

Noting that most visitors were maskless, Lyle says, “It’s nice to see people smile.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Summer 2021: Vacation demand is up in beach towns, but shortages hurt