Continuing COVID-19 vaccine trials may put some volunteers at unnecessary risk. Is that ethical?

The first two COVID-19 vaccines to complete clinical trials have been so successful they raise concerns for the next ones.

Is it ethical to give people a placebo when a lifesaving vaccine is available? Should those who received placebos in the first two trials be given preferential access to active vaccine to thank them for their sacrifice?

There is no consensus among ethicists and public health officials on either point.

Moncef Slaoui, chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, the Trump administration program leading the vaccine development effort, said trial participants should be first in line to be vaccinated. They were not mentioned Tuesday in a meeting by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention board that recommends who should get the vaccine first.

Candidate COVID-19 vaccines, one made by Pfizer/BioNTech and the other by Moderna, appear poised to receive FDA emergency use authorization within weeks after showing they are safe and more than 94% effective. The companies conducted large trials of 44,000 and 30,000 people, respectively, in which half of the volunteers received a placebo. Participants don't know which they received.

Typical vaccine trials last for two years. Both groups are followed to ensure safety and indicate how long the vaccine's protection will last. During a pandemic in which an American dies of COVID-19 every minute, officials determined a two-year delay unacceptable.

Ending the placebo group early comes at a price.

“We don’t have the full profile on these vaccines,” said Norman Baylor, president and CEO of Biologics Consulting and a former director of the Office of Vaccines Research and Review at the Food and Drug Administration.

Continuing to compare the placebo and active vaccine groups could help researchers better understand how different demographic groups, such as the elderly, respond to the vaccine and identify any unexpected longer-term health issues.

That information will never become available, Baylor said, if placebo recipients are vaccinated in the coming months.

What happens to those who got a placebo?

No one wants to penalize people who volunteered to help researchers learn about vaccine safety and effectiveness, said Dr. Walter Orenstein, associate director of the Emory Vaccine Center, former director of the immunization program at the CDC and a volunteer in the Moderna trial.

“I am concerned about the ethics if I can’t get it, whereas everybody else with my characteristics can get it,” said Orenstein, who sits on Moderna’s Scientific Advisory Board. “When it’s made available to the people in my category, I should be able to be unblinded and get it.”

Trial participants shouldn't be moved to the head of the line, said Franklin Miller, a professor of medical ethics at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

If the more than 35,000 people in the placebo groups of both trials were prioritized, that would defer vaccinations for 35,000 health care workers risking their lives every day to treat COVID-19 patients, he said.

Of course, if a trial participant is also a health care worker, that person should get the vaccine with his or her peers, Miller said.

Arthur Caplan, professor and founding head of the division of medical ethics at NYU School of Medicine in New York City, said he thinks the only ethical thing to do is to identify the people in the placebo group and let them get vaccinated, leaving the study if necessary.

"That's really going to damage your trials," Caplan said, because it won't be possible to compare the two groups over a longer time period.

Because someone in the placebo group of the Moderna trial died, who presumably would have survived if vaccinated, "you have no choice but to unblind" the trials and offer people in the placebo group a vaccine as it becomes available, he said.

Caplan hopes people in both groups will be followed, even after vaccination, to reduce the harm to research, but it's not clear whether the companies – stretched thin trying to produce the vaccines – will have the wherewithal to track participants, he said.

A World Health Organization committee came to a different conclusion than Caplan. It argued Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine that larger-scale trials involving hundreds of thousands of people should be started to look for rare effects that haven't been seen in the first 35,000 participants. Those in the placebo group could be vaccinated two months later, minimizing ethical concerns.

"Such a trial could be conducted either during a period of emergency use or immediately after licensure and could be viewed as a fair way of allocating initially limited vaccine supplies," according to the 20-person international group, which included statisticians, infectious disease experts, epidemiologists and other scientists.

One other possibility: Ask people in the trial, including placebo recipients, to stay for altruistic reasons, delaying vaccination for the sake of scientific understanding.

That would be ethical as long as people are fully informed about the availability of an effective vaccine, said Mildred Solomon, a faculty member of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School and president of the Hastings Center, a nonpartisan bioethics think tank.

"The bedrock principle in human research is that there must be voluntary and informed consent," she said.

How to test going forward?

Scientists are divided on how to test other COVID-19 vaccines, now that the first two have proved so effective. For the next few months, until they become widely available, there is no issue, Slaoui and others said.

Once anyone can walk into a drugstore or doctor's office and get a two-dose vaccine likely to be highly effective against COVID-19, it will be harder to justify giving someone a placebo.

This is a “thorny issue,” agreed Dr. Mary Bassett, director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University and the former health commissioner for New York City. “It would serve the public best if people continue in the trials as they were enrolled.”

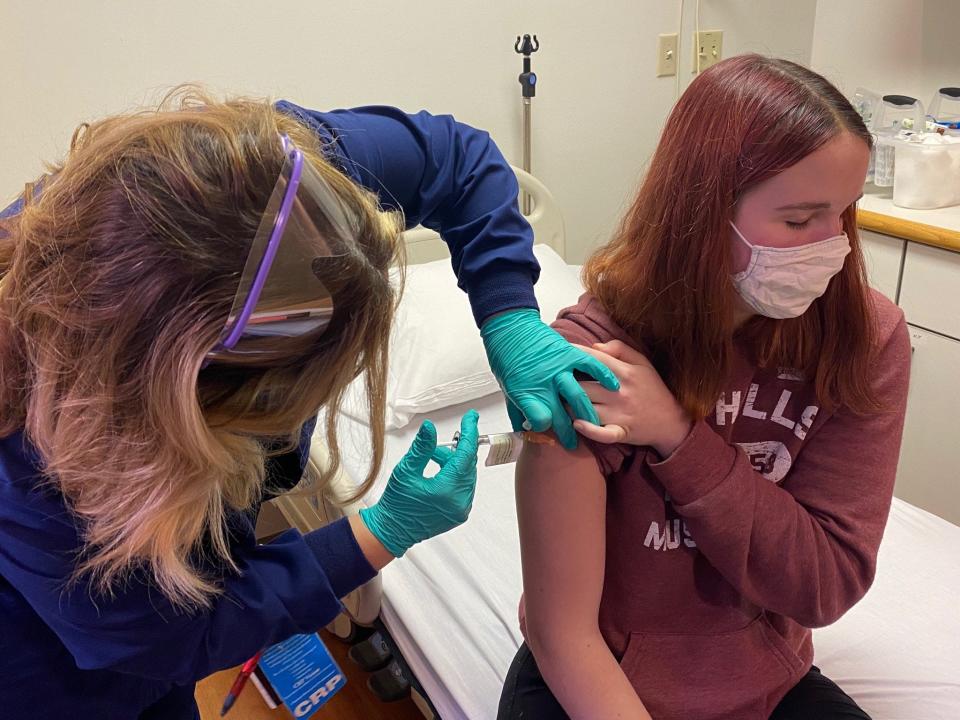

Teenagers have been participating in the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna trials, randomized to receive either a placebo or the active vaccine. Those trials have not advanced enough to reveal effectiveness, so there is no ethical quandary in continuing placebo-controlled research in that group.

Younger children have not been allowed to participate in vaccine studies because it's not clear what dose they would need or how they would react to the vaccine. Similarly, there is no information on pregnant women, because they haven't been studied, so the ethical concerns seen with adults aren't relevant.

Hopefully, people will participate in trials of other candidate vaccines, Solomon said, even if they stand a chance of receiving a placebo and no personal benefit.

"There's so much more we need to learn that it would be a real pity not to pursue randomized trials for additional vaccines. We need more vaccines," she said. "But researchers must do it in a responsible way that ensures fully informed voluntary consent."

Even if a later vaccine is less than 94% effective, it might be preferable to the two front-runners in some situations, Miller said. It may require only one dose, such as a candidate being tested by Johnson & Johnson, or is cheaper and easier to distribute in lower-income, rural areas, such as a vaccine being produced by AstraZeneca and Oxford University.

"It's all the more important to keep those trials going, because that could be a vaccine that goes to many more people" than the Moderna or Pfizer/BioNTech ones, he said.

In future trials, vaccines should be compared against the two known to work, rather than against a placebo, said Dr. Peter Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

That way, everyone will get either a highly effective vaccine or another active vaccine that will hopefully provide similar benefits – and no one will be left unprotected.

Drug companies don't like such head-to-head comparison trials, he said, because their vaccine might not look as good as someone else's, but it's in the public's interest to know whether some vaccines are more effective than others.

"These are artificial constraints due to this idea that private industry must make their own products, because those are the ones they can capture the revenue from," Bach said. "If the answer is Pfizer and Moderna's vaccines save more lives, we should be making more of these products."

Contact Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID vaccine trials: Ethical to continue after Pfizer, Moderna news?