Colleges and universities owe Black people restitution. It’s long past time to pay.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The thought of reparations for Black people paralyzes even the most liberal, open-minded officials and alumni of America’s leading institutions of higher education. Yet, colleges and universities owe Black people restitution.

As scholar Craig Wilder aptly points out in his work, "Ebony and Ivy," dozens of the top research universities and liberal arts colleges have a connection to wealth accumulated from slavery. The question that follows is: How do these institutions make up for their pasts?

In 2003, the Ivy League’s first African American president, Ruth Simmons, whose campus was erected (at least in part) by enslaved people, boldly established the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice to survey the depths of Brown University’s links to enslavement and the trade of humans. Simmons’ act was particularly courageous as no other elite institution had so publicly situated itself in the narrative of slavery.

Acknowledgment was a first step. From there, the university set about officially studying its relationship to slavery with the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. Then, Brown memorialized the university’s tragic role with a monument erected on campus. Financial recompense for those families of descendants who were harmed is the logical next step.

Structural justice for Black people is always slow to come in the United States. In many ways, it is easier to call for the accountability of a murderous police officer who chokes a Black man to death on camera than it is to make up for the systemic racism of U.S. institutions. The images of Americans unnecessarily perishing at the hands of police and vigilantes during a moment when the COVID-19 virus held the nation hostage was enough to jolt some officials at predominantly white educational institutions into further self-reflection about their history of harming Black citizens.

If a higher education institution was a participant in the race-targeted disempowerment of Black communities, then reparations are owed. Edifying steps toward repayment are straight forward: acknowledgment of harm, deep investigation of the actions and identification of those harmed, requests for forgiveness from the harmed party, mutual agreement upon recompense and, hopefully, reconciliation.

Some progress, not nearly enough

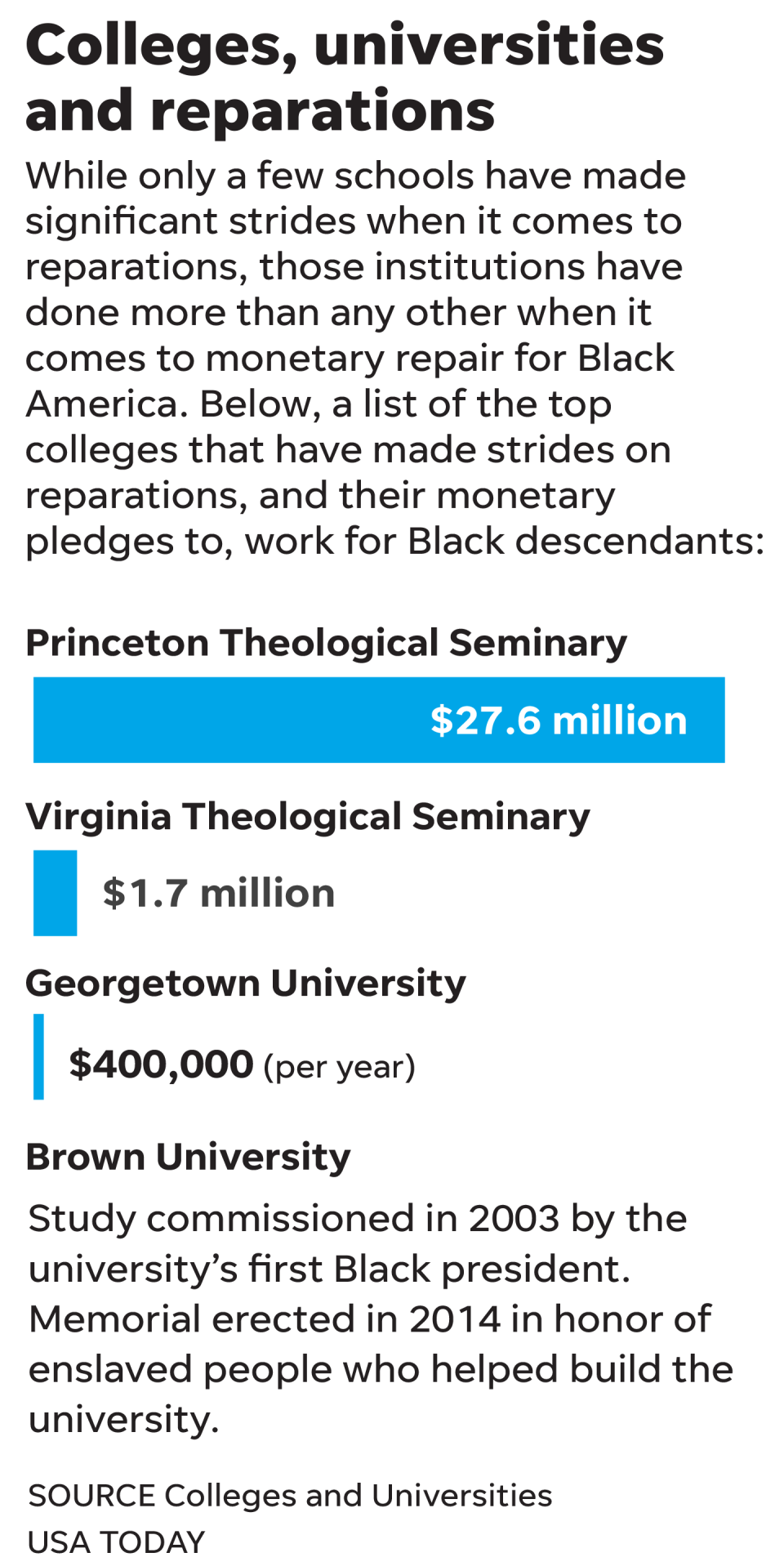

For some schools, reflection resulted in decisions to offer financial reparations in atonement for institutional ties to slavery.

Famously, in 2019, Georgetown University’s student body voted to create a fee to raise funds for reparations after learning of the university’s sale of 272 enslaved people to finance the institution. With reconciliation in mind, officials at the Catholic Jesuit institution took the lead in pledging to raise $400,000 a year to help descendants, who are being identified by way of archival research and DNA testing.

Princeton Theological Seminary went a step further to pledge $27.6 million for reparations in the form of “scholarships, curricular reforms, and community outreach.” That would include 35 scholarships and fellowships for descendants and other members of “underrepresented groups.”

To be clear, in the case of Georgetown and Princeton Theological Seminary, it took African American and progressive students agitating to push the institutions to do right by their histories.

Recompense in the form of money or land, especially with respect to Black suffering, is unusual and uncomfortable for America – even when the evidence of harm is overwhelming. Victims and families of race riots in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and elsewhere of the early 20th century have not received financial restitution. Smaller cities like Evanston, Illinois, and towns like Amherst, Massachusetts, (both in the North) have vowed to extend reparations.

When the many U.S. higher education institutions claim justice in their missions and goals, however, monetary repayment for previous acts of racism should be part of the work. As some of these colleges and universities have existed prior to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, it is time they confront the concept of reparations.

Many Americans recently became acquainted with the concept of reparations by way of Ta-Nehisi Coates, who penned the 2014 Atlantic article “The Case for Reparations.” Of course, enslave and formerly enslave African Americans and leaders made the case for reparations before slavery ended. What made Coates’ take particularly useful is his emphasis on the fact that American institutions owe reparations not just for their links to slavery but also because of their deep adherence to Jim Crow policies of de jure and de facto racial segregation.

Up to this point, it seems that mostly private higher education institutions have taken the lead in considerations of reparations. Large state-funded institutions have benefited just as much (if not more) from discrimination and racism. To illustrate the point: I had dinner with the first African American tenured professor at the University of Missouri. An institution that slaves helped build didn't tenure a Black educator, Arvarh Strickland, until the late 1960s. He was my mentor and remained an important figure in my life until his death in 2013.

The first admitted Black law student at the University of Missouri, Lloyd Gaines, had to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court for entry. Admission was granted in 1938, but the following year, Gaines went missing and was never heard from again.

These early pioneers were mistreated and marginalized. Their families deserve recompense, as do the Black people in Missouri (and other states) who paid taxes but were denied admittance and employment because of their race.

Institutions of higher education, however well meaning, are relatively new to the conversation of reparations. They should consult with and center the needs of those who have been most affected by the racism, mistreatment and marginalization. Furthermore, they should enhance the efforts of those who have already laid the groundwork in the struggle. Democratic legislators like Sheila Jackson Lee, of Texas, and the late John Conyers who put forth HR 40.

Since the 1980s, organizations like the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America have devotedly campaigned for reparations. Higher education institutions could also use funds and resources to bolster the work of historically Black colleges and universities, which have always sought to improve opportunities for Black learners.

Stop navel-gazing, do the right thing

Some university and college officials are contemplating what reparations look like on campus, and they are cautious in decision-making. If these schools are genuine with respect to their Black Lives Matter statements, they should be as intrepid in repairing the harm as they were when damaging Black families and their life chances. At present, it is en vogue to acknowledge institutional ties to slavery, yet reparations have not, unfortunately, been an established response to those acknowledgments.

Again, acknowledgment is a good first step but not a destination. For repair to be sustainable, it must be a prominent part of budgets, curricula, admissions and culture.

I was once asked to lead a committee to explore an institution’s connection to slavery. When I queried whether funds for reparations for the affected families and local Black community had been arranged, the requester grew silent. I refused to take up the task of studying the trauma of Black people only for the institution who harmed those Black people to further benefit from the marketing of such a study. I told the requester that such an effort without reparations amounted to navel-gazing at worst and virtue signaling at best – neither of which would help Black life chances.

The universities and colleges with ties to slavery and Jim Crow have stymied the earnings and potential wealth of Black families and crippled entire Black communities while not paying income taxes.

As Davarian Baldwin shows in his new book, "In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower," they marginalize Black people by way of their expansion and admission policies. Those residents whom these institutions have displaced should be considered for reparations.

Additionally, in the case of Black athletes, institutions – particularly large public universities like those in the very popular collegiate sports leagues – have exploited Black labor and talent while reaping great monetary benefits from the likenesses of student-athletes who could not receive pay (beyond tuition and board) for their efforts on the court or field. Whatever money the institutions made beyond the tuition and board could be repaid to current and former athletes.

Institutions have gained acclaim and money from the images, documents and remnants of enslaved people. As did some museums abroad, universities and colleges should consider returning the artifacts to the families of the original owners or paying an adjusted rate for them. If institutions are serious, then financial restitution should be extended to Black families, as well as students, faculty, staff and community members.

Of course, there is no way to ever fully repay African Americans for the wretchedness of slavery, Jim Crow and racism in which the nation’s top universities and colleges participated. But there is an obligation to try in the name of resistance.

As federal officials will undoubtedly be encumbered by politics and bureaucracy, universities and colleges are best suited to lead the way in a localized manner. If these higher education institutions use their ample resources to right the wrongs of the past, perhaps future generations will learn that American redemption is possible – and that justice is attainable.

Stefan M. Bradley is visiting professor of Black studies and history at Amherst College. He is author of "Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power and the Ivy League."

For more on reparations, visit reparations.usatoday.com

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black people are owed reparations by colleges and universities.