How is climate change affecting South Florida? Water managers want to know

For the first time, water managers set out to analyze exactly how climate change is affecting canals, pumps and the many structures that control water flows in South Florida.

The South Florida Water Management District on Friday presented an initial plan to develop its water and climate resilience metrics, a set of data that will help the district better protect cities from flooding while making sure that people, farms and businesses get the water they need.

The initial findings show what has been long known: Climate change is causing heavier rainfall, and sea rise is flooding communities more often, turning freshwater wells salty and forcing the aging system to work longer and harder to keep South Florida dry.

Last year’s wet season underscored the growing challenges to flood control. A wild storm season that started with record-breaking rainfall in May and ended with a double landfall by a very wet Tropical Storm Eta filled up canals and conservation areas to the brim. Even before the storm hit, water managers and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers were trying to figure out how to make room for the expected deluge in canals and water retention areas already swollen from months of regular rains.

Carolina Maran, the district’s chief resilience officer, wondered how much of what South Florida saw in 2020 was a result of climate change, and how significant the events were compared with the district’s own historical records.

“Are these events part of a long-term trend in terms of magnitude and frequency that would impact the way we manage our systems today?” Maran said during the district’s first workshop on the metrics. “In this context, it becomes evident that the development of metrics that can help us answer these and many other questions is really important.”

Because South Florida is so flat and has been severely drained and altered over decades, it’s challenging to keep saltwater at bay and control flooding. If water managers need to close gates to prevent sea water from moving inland through canals during high tide events, they have less flexibility to move water around to prevent flooding. The district is constantly working with these competing goals, and climate change is only making things more challenging.

An initial set of 15 metrics is being prioritized, including tailwater and headwater elevations at coastal structures, high tide events, groundwater levels, rainfall, flooding events, water temperatures, soil subsidence and salinity in the Everglades.

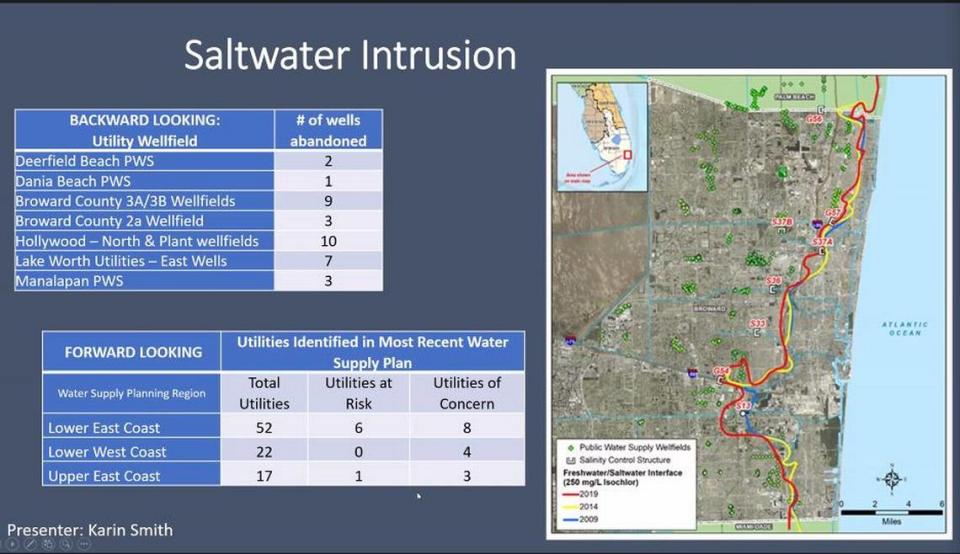

District scientists also saw the fingerprints of sea level rise on the region’s water supply. As sea levels rise, the denser saltwater pushes inland and begins to contaminate freshwater wells in a process called saltwater intrusion.

“As sea levels are rising, the groundwater levels are definitely showing that trend also,” said Karin Smith, a principal scientist with the district’s water supply bureau.

Smith’s cursory look at the last 20 years found that municipalities have abandoned at least 35 wells because of their saltwater content. Ten of those were in Hollywood.

With further study, Smith said she hopes to produce a map that shows how many wells have been abandoned district-wide and how many more are at risk in the future.

One factor the district didn’t talk much about during the meeting was carbon emissions, which drive climate change.

“We recognize this as an important factor we are not yet tracking,” Maran said.

She noted that in 2020 the district was forced to run its handful of mechanical pumps more than ever before due to the deluge of rain, both from Tropical Storm Eta and the record-breaking rainfall totals. Those hours of use are only expected to go up as the world warms.

“That’s definitely something we want to track,” she said.