Brooke Shields Reveals She Was Raped by Hollywood Insider in Powerful Sundance Doc

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Brooke Shields is a little girl, likely 11 years old, or even younger. Appearing on a talk show, the male, middle-aged host smiles at her leeringly. He calls her a “pretty girl.” Did she know that, he asks? The studio audience looks on, some baffled and some indifferent, as if this was quite normal. Does she enjoy all the fuss, he continues? Shields’ blue eyes are more piercing than you might remember. And, in this instance, they’re completely vacant, as if she has dissociated.

This is the opening scene to Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields, the two-part documentary that premiered Friday at the Sundance Film Festival. The footage is shown as audio from a new interview with Shields plays. “It felt so arbitrary and unmerited,” she says, about the fascination with her beauty when she was so young. That anyone called her an icon was something she wasn’t capable of processing.

“I was born with this face, so I didn’t want to think about it,” she says. “I wanted to think about things I could control. Things that could have happened without beauty.”

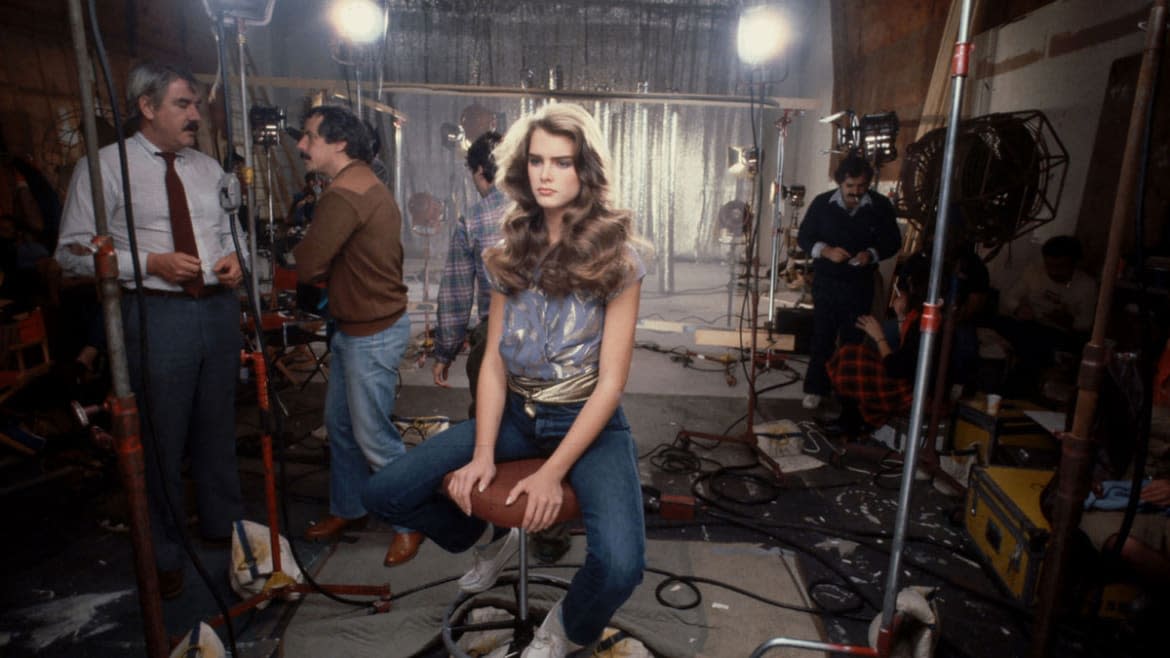

Pretty Baby, which was directed by Lana Wilson (the Taylor Swift documentary Miss Americana), chronicles Shields’ entire career, from when she first started modeling at 11 months old in a soap ad to present day, when she is finally ready to reckon on a public stage with her fame and the ways in which she was exploited and traumatized by the industry. It’s empowering and it’s powerful, a portrait of a constantly transforming woman on the journey to finally, now, understanding her identity and the power of her own agency.

Lana Wilson, Brooke Shields, Alexandra Wentworth and George Stephanopoulos attend the 2023 Sundance Film Festival premiere of Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields.

(Warning: Descriptions of sexual assault follow.)

The film also contains what is sure to be a headline-making personal revelation. For the first time, Shields speaks publicly about an alleged rape she experienced by a major Hollywood player.

After Shields attended college at Princeton University, one of the first occasions in her life when she actively worked to reclaim the narrative scripted for her and identity assigned to her by the media and entertainment industry, she struggled to book new acting roles. She slummed it filming commercials and doing infomercials, but got excited when she heard about a movie that an old friend of hers in the business was working on.

Their meeting about the project at a restaurant felt off. When it was over and she said she was getting a cab, he invited her to his hotel room to call for one there. He disappeared into the bathroom, and, she says, re-emerged naked. They tussled as she said “no.” likening it to wrestling. “I didn’t fight that much,” she says. “I absolutely froze. I thought, ‘Stay alive and get out.’”

From her years on film sets as an adolescent and teenager filming nude scenes and sex scenes that she now realizes she was uncomfortable doing—and as we saw in that first talk show clip—she “had practice being dissociated.”

When she phoned her bodyguard to tell him what happened, he told her, “That’s rape.” In response, she said, “I’m not willing to believe that.”

Brooke Shields: Barbara Walters’ Creepy Interview With Me Was ‘Practically Criminal’

Discussing what had happened with her friend Ali Wentworth, who produced Pretty Baby along with husband George Stephanopolous, she admits, “There was a part of me that felt cool,” like it was “validation”—a feeling she admits now to be so complex, yet misguided. The man said to her, “I can trust you, and I can’t trust people,” after it happened. She convinced herself somehow that it was her fault. Later, she recontextualized what had happened to her and sent him a scathing letter, saying that she was above him. Then she moved on.

The way this event is revealed in the film and, more specifically, how Shields speaks about it—the process of evolving her feelings and questioning her perspective—is emblematic of what makes Pretty Baby so moving and, certainly, compelling.

Shields spent decades as one of the most famous women in the world. She’s lived what could be considered an outrageous life, something that Pretty Baby isn’t shy about confirming.

She was a child star who became the lightning rod for an international discourse about the sexualization of minors. After her controversial Calvin Klein ads sent her to a new stratosphere of celebrity with the fiery force of a flamethrower, TIME crowned her face, “The ’80s Look.” (Defining a generation’s beauty made her feel awkward: “I don’t do anything to my eyebrows. Why do my eyebrows have to be a thing?”) She was friends with Michael Jackson, was married to André Agassi, and had an infamous back-and-forth with Tom Cruise over the use of antidepressants.

Plus, even if you have been following Shields for decades, there’s no escaping the surprise over how upsetting and grotesque those talk-show interviews with her were at the beginning of her career. (And, as Pretty Baby shows, there were a lot of them!)

But, as Stephanopoulos told the Sundance audience after film credits rolled, there was also so much about her life that is universal.

What it means to constantly struggle with a relationship with a parent, as she did with her mother, who was an alcoholic and also her manager. How to navigate one’s own sexuality in a culture that exploits it, and in an industry in which toxic masculinity thrives. How to deal with an unhealthy marriage. (Another bombshell of the film is the tantrum that Agassi throws after seeing Shields lick Matt LeBlanc’s hands during her career-comeback guest role on Friends; he apparently went home and smashed all of his tennis Grand Slam trophies.)

And, of course, how to transform yourself after the world limits you, tires of you, or discards you altogether.

There’s a pivotal anecdote in the first part of Pretty Baby. Shields had been offered to write a book called On My Own after her first year of college, in which she would pen essays of advice to other teenagers anxious about being on their own for the first time. She took it seriously and was proud of what she came up with. Her publishers, however, rewrote everything, instead including suggestions about what leg warmers would be most fashionable and diet tricks to avoid the Freshman 15. She was dismayed, but decided to go along with it; it was easier that way, and what she thought she was supposed to do.

What we see by the film’s end however, is the work it took for Shields to board the pendulum and swing to the other side of that attitude: to really think about the toll everything that happened to her took on her, how her actions at the time shaped her, and what she could do now to find a healthy, meaningful relationship to it. That means to her past, her present, and her future. She shares these stories because they might help other people. But she shares them because they might still help herself.

“It is the first time in almost 56 years that I am owning my identity fully,” she says near the end of the film. That’s the Pretty Baby—and the Brooke Shields—lesson: What better time than now?

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.