Beyonce, Whitney, Aretha and more: New book sings ‘in Praise of Black Performance’

It has been a little more than 51 years since gospel singer Merry Clayton made her way, in pajamas and curlers, to a Los Angeles recording studio to belt out some of the most memorable backup vocals in rock music history. The hour was late, around midnight. Clayton, who was pregnant, had been called out of bed. But she practically blew Mick Jagger away on the track for the Rolling Stones hit “Gimme Shelter.”

Raaaape, murderrrr. It’s just a shot away. It’s just a shot away.

Hanif Abdurraqib joins the legion of admirers in his new book, “A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance.” “It is good,” he writes, “to sing the word ‘murder’ like you fear it, but better to sing the word like you aren’t afraid to commit it.”

As always with Abdurraqib, there’s more to take from that incendiary 1969 recording session and from Clayton’s long career. He tempers his remembrance with lament, first that, tragically, she suffered a miscarriage shortly after returning home. Maybe it had been the strain of the session. There was no way to know.

But it was also the fact — and here is where Abdurraqib lends another perspective — that while this powerful Black singer was coveted by the likes of the Stones, Joe Cocker and Carole King for her backing vocals, she never could carve out more than a moderately successful career as a solo artist. Clayton was denied the full measure of fame she helped create for others.

“Even the greatest singer who is relegated to the background has a hard time expanding out of it,” Abdurraqib writes. “To be known in this way is to be barely known at all. To be buried in history, in a grave with no marker for your name.”

That — the invisibility of too many talented African Americans until they can fill some need, serve some purpose beyond the Black universe — is one of the themes that courses through “A Little Devil in America.” Released March 30, it reaffirms the 37-year-old Abdurraqib as one of our country’s most incisive contemporary writers, be it through prose or poetry. He produces both, the rhythms of one frequently bleeding into the other.

The Kansas City Public Library has made “A Little Devil in America” its latest “book-of the-moment” FYI Book Club selection.

The title comes from a speech by flamboyant, St. Louis-born entertainer Josephine Baker at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. “I was a devil in other countries, and I was a little devil in America, too,” she said just ahead of Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” address.

Baker is among those featured in the book, a penetrating meditation on Black culture and creativity and its place in broader American culture. Abdurraqib weaves personal stories and reminiscence with sharp analysis in illustrating how Black people have historically lifted and inspired other Black people, in many cases through performance. Always, however, there is the specter of racial divide.

While white people in the country may share an appreciation for Black artistry, Abdurraqib observes that it’s too often only as consumers. It’s artistry as a commodity.

Dave Chappelle, whose brilliantly discomforting “Chappelle’s Show” ran on Comedy Central from 2003 to 2006, “got to be everyone’s Black friend for a while. The one that stays at a comfortable enough distance but still provides a service.”

Singer Whitney Houston was packaged as a white-digestible pop princess, to the point of provoking African American backlash. “In order for her to take on the pop world like no Black woman musician of her era ever had before,” Abdurraqib notes, “she had to be written about in a way that placed her above and outside the narratives of other Black musicians.”

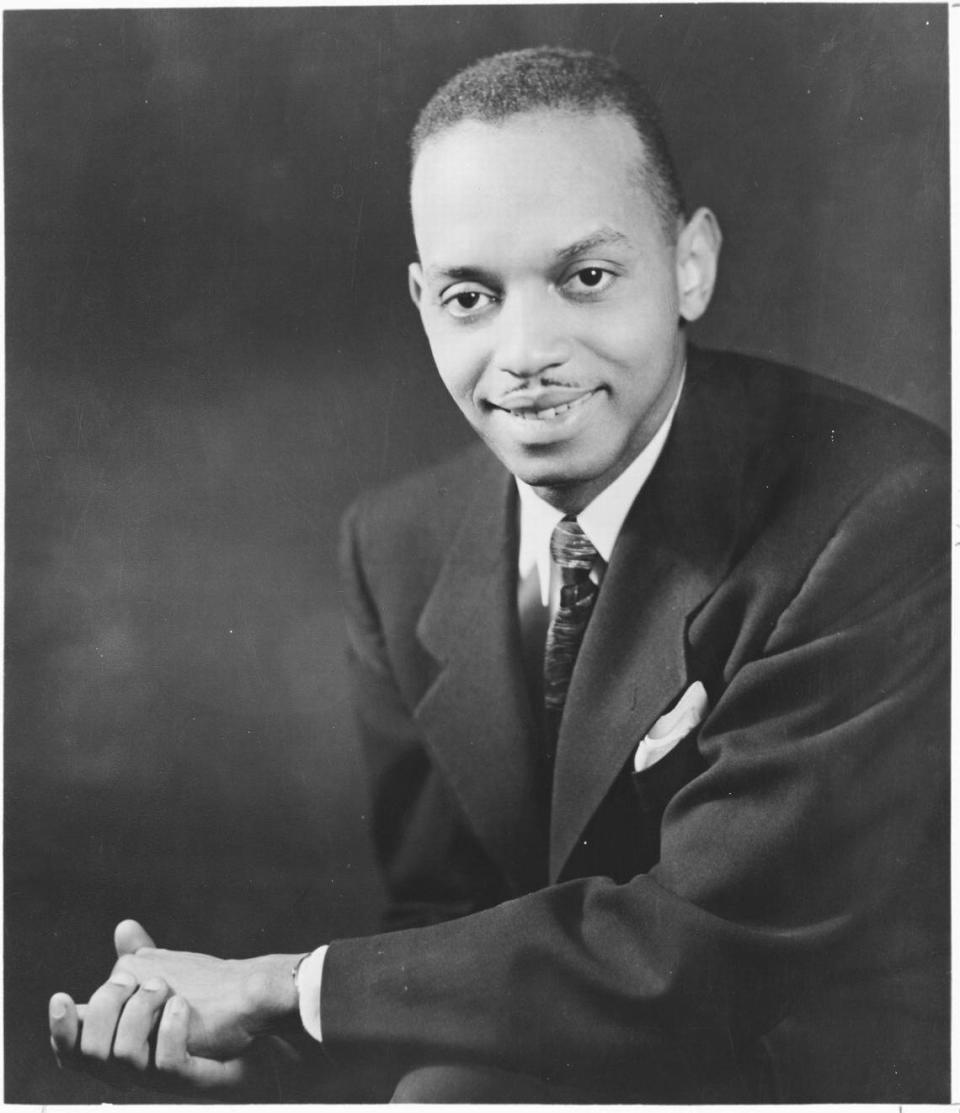

Plenty of people, including Abdurraqib, took offense at what they saw as the triteness of the Oscar-winning movie “Green Book,” the story of Black pianist Don Shirley and his tough-talking, Italian American driver and bodyguard. But for Abdurraqib, cliché wasn’t the lone flaw.

Shirley walked away from music for a time over the “lack of upward mobility” for any African American who preferred classical music to jazz. He worked as a psychologist, studying the relationship between music and juvenile crime. But the film found no room for that.

“I love this small sliver of the life Don Shirley lived,” Abdurraqib writes. “That in a country still obsessed with Black people solving problems they didn’t create, Don Shirley walked away, answering only to himself and his own musical curiosities.”

He also examines the effortless cool of Soul Train host Don Cornelius, Aretha Franklin’s ability to make songs “close to something holy” and Beyoncé’s stunning homage to the Black Panther Party at halftime of the 2016 Super Bowl — “a tribute to one of her people’s most revolutionary movements, in the place of that movement’s birth … with a message so loud it didn’t have to be spoken in order to be heard.”

Kirkus Reviews calls the 37-year-old Abdurraqib “a writer always worth paying attention to.” His first collection of essays, 2017’s “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us,” was named a book of the year by Buzzfeed, Esquire, NPR and The Oprah Magazine, among others. He was long-listed for a 2019 National Book Award for “Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to a Tribe Called Quest,” a chronicle of the pioneering hip-hop group that became a New York Times best-seller.

He has released two collections of poetry, both to acclaim. “A Fortune for Your Disaster” won the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize last year as the “most outstanding book of poetry published in the United States.”

Abdurraqib, who lives in Columbus, Ohio, recently spoke with The Star about “A Little Devil in America,” poetry vs. nonfiction, and his perspective on Black excellence and race relations in our nation. Excerpts are edited for length.

Q: There’s a lot in “A Little Devil in America” to take in. What did you want to stick with readers?

A: I hope people take away … a curiosity to explore these histories on their own terms and think a bit more deeply about humanity as it relates to consumption, which I think is challenging for all of us — myself included.

I didn’t come to this book from a position of self-righteousness or that my ideas on this are finished. Of course, like every Black person in America, I think I have a unique perspective on the way humanity is devalued in the name of celebrating things. But I did not want to present myself as an authoritative voice or someone who’s wagging a finger, so to speak. I’m asking people to understand that there’s importance to honoring the full life of someone beyond what they can provide you by way of consumption.

Q: Is it the same for readers who are white as it for those who are Black?

A: I guess I can’t say for sure. But my hope is that it might be. So much of the book was written with a Black audience in mind and not to explain what people already know. But there are other folks who might be outside that circle who are seeking explanation and, through their seeking, might come to different, better conclusions. That’s a bit exciting for me.

Q: You express an inner anguish about the state of race relations today, at one point writing, “I have yet to be given enough in this country that might silence the ache that arrives when a video of a Black person being murdered begins to make the rounds.” Are we failing in this era of Black Lives Matter to move the needle?

A: It depends on how you define it. I don’t think the needle has moved to my satisfaction. But I’m also aware and hopeful that there are ways it’s moving that I just won’t see, that I won’t be aware of yet … and that 10 years from now, I will look back and say, “OK, I can see how this thing and this thing and this thing led to the world I’m living in now.” It’s just hard to see that in the moment.

Q: You have some interesting reflections on violence … between boxers in the ring, youngsters in schoolyards, even you and your older brother. Are you speaking to its inevitability? Does some degree of violence serve a purpose?

A: I think so. I think rage serves a purpose. I mean, violence is embedded into the very fabric of American history. To me, to reform that — the country as it is — is at some point going to require violence to some degree. I also talk a bit about gangs and how violence is a tool of protection. I don’t want to gloss over that, either.

Now, I am not someone who wishes for interactions to come to violence. But I also understand that violence is a tool in the larger toolbox of revolution, of quote-unquote resistance, of reimagining a better world. Is it a tool I personally reach for first? Absolutely not. But it’s a tool that I think is almost required to understand all that I can be capable of in order to protect the people I’m fighting alongside and fighting for. And to protect the imagination of a future that serves us all.

Q: You write about working as a bill collector, and you had a job with a health care startup as recently as 2016. Did it take you awhile to get around to full-time writing?

A: Even when I worked some of those jobs, I considered myself a writer. But I didn’t take on writing full time until 2017.

I love that I came up in working-class situations, particularly serving (in restaurants). I worked at a breakfast restaurant for a couple of years because the schedule was conducive to my writing. I would get up at like 6 or 7 in the morning and work a shift until 1 or 2 and then have the rest of the day off. There was something really cool about the process of sinking into the lives of people I talked to and knew … and building relationships and finding out how to tell a story in a quick enough pace that it did not bore them.

Q: Your poetry seems to seeps into your narrative, into this book. How did the blending of genres evolve?

A: The biggest thing, and it might be the least exciting answer but it’s true, is that I don’t really think about it. Part of it is because so much of my poetry … shares the function of storytelling. I just think language, beautiful language, is a vehicle for that. It’s like a vehicle … to draw people in or draw people closer to a long, winding story.

For me, it’s not necessarily blending genres. It’s just returning to my toolbox and asking, “Well, what do I have at my disposal that will make people stick around a little longer? What will keep people here?”

Q: You once said in an interview, “I want to do the difficult, riskier thing.” Do you think you’ve done that, by and large? And how does staying in Columbus all but 2½ years of your life fit with that?

A: In some ways, that (remaining in Columbus) is the difficult thing. To be tasked with loving a place is also to be tasked with making it better, with improving it to a scope you feel it can rise to. It’s not so much living here but loving the fact that I live here and believing in this place as something beyond what it currently is … that’s the hard part.

There’s also the idea that what I’m actually trying to do is cultivate a real generosity for myself in a place that isn’t always generous — and isn’t always generous to people I know and love and care about. That’s a challenging thing I think I embrace.

Steve Wieberg, a former reporter for USA Today, is a senior writer and editor for the Kansas City Public Library.

Join the discussion

The Kansas City Star partners with the Kansas City Public Library to present a book-of-the-moment selection every six to eight weeks. We invite the community to read along. Kaite Mediatore Stover, the library’s director of readers’ services, will lead an online discussion of Hanif Abdurraqib’s “A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance” at 6:30 p.m. Thursday, May 27. via Zoom. Email Stover at kaitestover@kclibrary.org for details on joining in.

An excerpt

“A Little Devil in America,” published by Random House, is divided into five multipart movements. In Movement 3, On Matters of Country/Provenance, Hanif Abdurraqib writes about musician Don Shirley and the treatment of his story in the film “Green Book.”

In the movie I’d like to make about Don Shirley, I want a room with four corners and a black piano in each corner. I want the piano keys to be whatever Don Shirley’s favorite color was, and if he didn’t have a favorite color, then I want the keys to turn whatever color he might see when he closed his eyes while listening to his own compositions. …

I want a movie in which Don Shirley is driven but doesn’t feel the need to speak to the white driver. A movie in which we don’t even know the driver’s name, but we know what Don Shirley’s favorite flower is by the way he rolls down his window and cranes his neck toward a field when the car drives by. I would watch the landscape change with him, in our shared silence, humming every now and again at something we found familiar.

Mostly, I want a movie about Don Shirley that allows for him to be seen through worthy eyes. One that doesn’t manipulate his story to serve the American thirst for easy resolution. If only all movies about Black people struggling against the machinery of this country were, instead, movies about Black people living.