Bettylu Donaldson, Kansas City activist and mentor to Jackson County youth, dies at 95

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s note: This feature is part of a weekly focus from The Star meant to highlight and remember the lives of Black Kansas Citians who have died.

The weather was cold and dreary the day Bettylu Donaldson brought her children with her into downtown Kansas City to speak up for their rights.

It was the winter of 1958, and the streets were lined with massive, cement-and-glass retail outlets — with short family names like Macy’s, Ike’s and Klines — that had only recently desegregated, lagging years behind most institutions in the city.

But Black residents like Donaldson and her family still weren’t permitted to dine in their cafeterias. Only white customers could. The doting mother instructed her three bundled-up kids, as young as 6 and old as 12, to keep moving with the rest of the protesters outside of the Jones Department Store at 12th and Main streets, recalls her daughter, Dianne Cleaver.

There were dozens of people marching from local Black groups such as the P.M. Interludes, the women’s professional association to which Donaldson belonged. They wore placards hanging over their coats, with a straightforward yet defiant message printed on them, worded so it could be reworn: “We protest racial discrimination in the serving of customers in the cafeteria or restaurant of this store.”

Dianne, who was 10 at the time, mainly remembers how freezing it was, and how badly she wanted to go inside the stores to warm up and get something to eat. Her mother calmly explained to her why they couldn’t.

“She made us go out, as little girls, and walk with her on the line,” Dianne said. “Whether it was that or an individual injustice, she would speak her mind to someone she felt was doing wrong, who impacted her or her family.”

Donaldson, whose lifelong belief in justice and equality led her to become an advocate for the youth going through the Jackson County juvenile court system, died on Jan. 5 following a years-long deterioration with Alzheimer’s, her family said. She was 95.

She was a part of many demonstrations during the historic seven-week department store boycott that ended in February 1959, when stores opened dining to all. A photo shows her standing in the middle of a large group of Black women and men, sporting plaid pants and a heavy coat underneath her placard.

Her toothy smile is warm yet slightly awkward, as the big huddled group tries to ready for the snapshot.

From the time she was growing up in Kansas City, Missouri, her family said, Donaldson was sharp and driven. She graduated from Lincoln High School at the age of 16.

That sense of purpose led her to serve a 27-year career with the county, climbing her way up from a deputy juvenile officer to the assistant director of juvenile court services, spearheading projects like halfway homes that helped young people in her community.

In 1971, the county named one after her: The Donaldson House.

Away from her work, as a full-time mother to four children, she was known to lead with her quiet and poised example, living a life of moral conviction where she said exactly what she believed. She answered countless calls and canvassed on behalf of a Democratic politician she believed in, her son-in-law, Emanuel Cleaver II, the 77-year-old Congressman and husband to Dianne.

“I was truly blessed to have a mother-in-law who successfully removed the words ‘in-law’ from her title,” Emanuel Cleaver II said. “She was always very kind to me and most supportive of me both as a pastor and as an elected official.”

Born Oct. 26, 1926 in a third-story apartment, Donaldson was the second and last child in her family. Her father was a firefighter, among the first Black chiefs in the city department, and he acted in a drama troupe — family recently uncovered clips of him preserved by the Black Archives of Mid-America. Her mother was a homemaker.

After Donaldson picked up her high school diploma ahead of her classmates, she went to Lincoln University in Kansas City for a bit and then crossed state lines to study education and speech-drama at the University of Kansas.

Dianne likes to remind her friends that, while she roots for both KU and the University of Missouri in sports, her mother was only allowed to go to one. Mizzou didn’t welcome its first Black students until 1950. Her first career out of college was teaching drama at Lincoln High School in the same classroom where she once sat, sharing her enthusiasm for the art with her students.

During that time, she married Davenport Donaldson, a chemist who — in her own words — was not the best dancer but charming nonetheless. She spent a few years as an educator before finding her life’s calling of helping juveniles in Jackson County. Though Dianne often wasn’t always aware of what her mother was doing day-to-day, she would see glimpses of her impact, like when the halfway house was unveiled to her. Her mother, always modest, never said much about the surprise honor; Cleaver still knew how big of a deal it was.

People would come up to Donaldson in public places, with Dianne by her side, and say she was like a second mother. They told she helped them when they were at their lowest.

“I would just run into people,” Dianne said. “There would be one or two people at our church who talked about how our mother helped them growing up, and how meaningful she had been in their life, believing in them and supporting them.”

But despite the conviction with which she lived her life, she made time for herself and the things that brought her joy. She was well-dressed, family said, and loved spending her hard-earned money at the Landing Shopping Center — her husband would tease her any weekend she didn’t go, saying, “They’re going to wonder where you are.”

She was a big fan of movies, too, especially the old and romantic ones. Her favorite was “Wuthering Heights,” from 1939, about two lovers torn apart by the tragic circumstances of their intersecting lives. She adored the work of Woody Allen, too, before molestation accusations tarnished his name in her eyes.

Marissa Cleaver Wamble, Donaldson’s granddaughter, described her as a beautiful and strong woman who took note of what those around her needed the most. Wamble, a self-professed introvert, felt Donaldson picked up on her reluctance to raise her voice.

“She showed me time and time again how to do it,” Wamble said. “She was kind but had no problem saying what was on her mind. As a woman — a Black woman — she was quite a role model.”

About 20 years ago, long before her Alzheimer’s robbed her of her ability to form complete sentences, Donaldson decided she was going to pen her own obituary and plan for her funeral. She would tap Dianne at church during a song she wanted for her service — like “God Is” and “When I Look Back Over My Life.” She made arrangements with the funeral home and the cemetery.

Dianne knows she simply didn’t want them to have to worry, as usual. Even in death, she felt most comfortable serving those around her, not the other way around.

“I’ve come to understand what gives my life its smile,” Donaldson wrote in her obituary. “It is my ever-present one-on-one with God; and the relationships I am privileged to share with my family and my friends.”

Her children and other relatives sat by her side in recent months to keep her company as she worsened. Dianne laid her phone next to her head as it played her favorite song, “Nature Boy,” by Nat King Cole. The track includes the heartfelt closing line that also captures the spirit of her life: “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn / is just to love and be loved in return.”

When they played the music, they were able to see that girl who went through school with the enthusiasm of someone who could change the world, who later showed her children how they should protest.“

She would look at you — and the spark in her eyes,” Dianne said. “You could see that she was still there.”

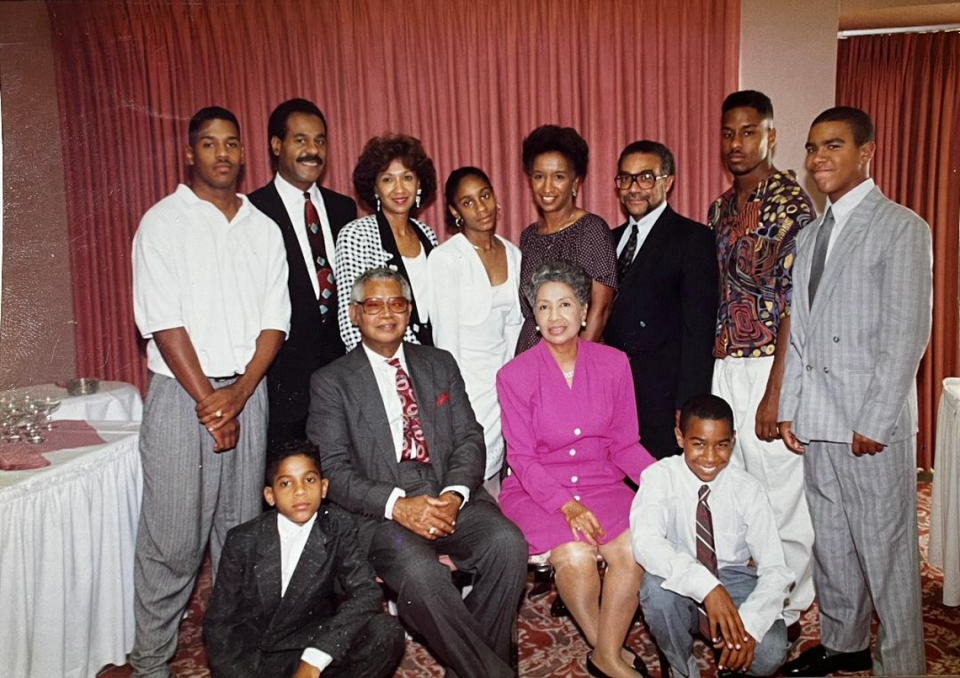

Donaldson is survived by her children, Dianne, Grace James, Garrett Donaldson and Bennett Donaldson; sons-in-law, Emanuel Cleaver II and Ivan James III; grandchildren Wamble, Emanuel Cleaver III, Emiel Cleaver, Jason James, Quentin James and Evan Cleaver; niece, Suzanne Lewis; and several granddaughters-in-law, step-grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Other remembrances

Oliver “Scooper” Singleton Jr.

Oliver “Scooper” Singleton Jr., a Kansas City, Kansas pastor who served as the council president of the city housing authority, died Jan. 7, family said in an obituary on the Mrs. J.W. Jones Memorial Chapel website. He was 79.

Born on July 30, 1942 in Poteau, Oklahoma, Singleton was the seventh child in his family. They moved to Kansas City, Kansas, where he was educated in the public school system, graduating from Sumner High School in 1960.

He met Lettie Watkins in 1970 and married her the same year, family said. They had three children.

Singleton worked for 15 years at the Certain-Teed Corporation, a manufacturer of building materials, and later was a driver for Robinson Delivery. He retired from that job, family said, but gained a new one: Associate pastor at ARK Christian Ministry in Kansas City. On top of that, he was the council president of the authority as well as the “overseer” of the Tower Plaza where he lived.

Singleton, known to loved ones by his nickname Scooper, was described as an avid reader and fisherman who had passion for martial arts and billiards. He loved to read his Bible and spoke about the goodness of the Lord every chance he got.

He is survived by his daughter, Billie Watkins; sons, Delvalon Singleton and David Singleton; brother, Aubrey Singleton; 16 grandchildren; 20 great-grandchildren; and several nieces and nephews.

Sheila Smith

Sheila Smith, a mother of six and natural caretaker who worked for more than 35 years as a cafeteria worker in the Kansas City Public Schools school district, died in her sleep on Jan. 5, her family said in an obituary, shared by Watkins Heritage Chapel. She was 79.

Smith was born on Jan. 10, 1942 in Springfield and educated in the city’s schools, graduating from Central High School. In 1962, she moved to Kansas City with her sister, Dorothy Agee. Five years later, she married her longtime partner, Robert Skinner. They had six children together.

Smith was described by family as a selfless person who felt happiest helping others, like she did for 13 years as a certified nursing assistant at Trinity Lutheran Hospital. She spent 37 years in Kansas City schools before she retired as a kitchen manager. She also loved blues music, family said, and was an usher and longtime member at the Metropolitan Spiritual Church of Christ.

Smith is survived by her sister, Agee; children, Darren Pasley, Latesa Hill, David Pasley, Larita Pasley, Lori Smith-Carroll and Dennis Smith; 13 grandchildren; 24 great-grandchildren; and many nieces and nephews.

Willie Gahagans Jr.

Willie Gahagans, Jr. a Navy veteran who had a love of helping people in his career as a caregiver, died Jan. 5 at Research Medical Center in Kansas City family said in a Serenity Funeral Home obituary. He was 68.

Gahagans was born Jan. 15, 1953 in Kansas City, Kansas, but grew up across the state line where he graduated from Paseo High School in 1971. He then attended Penn Valley Community College, receiving his associate degree in education.

Gahagans enlisted in the Navy and served for five years before he was honorably discharged, family said. He went on to live in San Diego for a decade after his time in the service. When he came back to Kansas City, he found his calling as a caregiver at the New Horizons assisted living facility and Always There Health Care. He loved to take care of others and try to make their lives better, family said.

He married Janice Elaine Freeman-Gahagans in September 1992 and they had three children.

Family described Singlton as a loyal and faithful man who loved life and to meet new people, of all different backgrounds. He is survived by his wife, Freeman-Gahagans; children, Rah’man Freeman, Rashaad Freeman and Madison Cawthon-Gahagans; siblings, Gina Gahagans and David Gahagans; seven grandchildren; one great-grandson; one expected great grandchild; and several nieces and nephews.