4 years after defeat, Bernie Sanders built a campaign that made him the frontrunner

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

DES MOINES, Iowa — For much of the Democratic presidential primary race, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and his supporters have felt ignored, particularly by the media establishment. But now, with just one day until primary voting begins in the Iowa caucuses, Sanders’s status as one of the top candidates in the crowded field is unmistakable.

Going into Iowa as the frontrunner is a far cry from 2016, when Sanders was a long shot against Hillary Clinton, and ultimately lost in a bitterly fought primary. This time around, however, Sanders has a campaign that has learned from past mistakes, lacks the infighting of four years ago and is putting forward a more potent — and at times personal — message, according to several senior advisers who spoke to Yahoo News.

It was hard to envision Sanders becoming a major force when he began his foray into presidential politics in April 2015 with a sparsely attended press conference on a lawn outside the U.S. Capitol building. Sanders cringed at the cameras and indicated he wouldn’t linger at his own debut.

“Let me just make a brief comment and be happy to take a few questions, but you don’t have an endless amount of time, I’ve got to get back,” Sanders said.

Despite his apparent discomfort with the spotlight, low name recognition and small initial campaign staff, Sanders’s message of fighting income inequality, universal healthcare and free public college and curbing corporate influence on politics caught on. One month after launching, Sanders held a formal announcement in his hometown of Burlington, Vt., that was attended by over 5,000 people. His rallies eventually filled arenas and Sanders won several states against Hillary Clinton, who had been widely expected to coast to the nomination easily. That late surge wasn’t enough to win, but that race laid groundwork that helped Sanders take a different approach for 2020.

“We had times when we didn’t know if we could raise any money that’s not the case now,” said Jeff Weaver, a senior adviser to Sanders. “He starts out with almost 100 percent name ID, he starts out with the capacity to raise lots of grassroots dollars. People not only know his name, but if you poll them, they know things about him. They know about Medicare for All, they know he’s aligned with working people.”

Weaver, who was Sanders’s campaign manager in 2016, described this year’s election as “fundamentally different” for the senator, who was polling in the single digits for the first two months of his last campaign.

Indeed, Sanders has led the Democratic pack in fundraising during this primary. And his 2016 agenda paved the way for a slate of progressive candidates and organizations who are backing him this time around, including three high-profile congresswomen of color who took office last year: Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich. and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y. The trio endorsed Sanders last October when his campaign was at a low point following a slow start and a heart attack that left the candidate in the hospital and fueled questions about whether the 78-year-old Sanders might be too old to mount a White House bid.

The congresswomen also helped counter a narrative that plagued Sanders in 2016, that his campaign and supporters were too male and too white. While Sanders struggled to appeal to people of color last time, a recent national poll showed him leading among nonwhite voters.

His campaign staff is also far more diverse than it was last time around. Sanders’s campaign manager, Faiz Shakir, is a Pakistani American and the first Muslim to lead a presidential campaign. The senior leadership also includes two African American women, former Ohio state Sen. Nina Turner, who is national co-chair, and René Spellman, who worked on surrogates and press logistics for Sanders in 2016 and is now a deputy campaign manager focused on California. A third woman, Arianna Jones, started the campaign as communications director and was promoted in late summer to deputy campaign manager with a leading operational role.

The infusion of new blood has fostered different factions on the campaign, according to a Democratic operative who worked on Sanders’s 2016 bid. Sanders’s team also had multiple camps in the last race, when his team had three power centers: Weaver, Tad Devine, Sanders’s chief strategist, and Michael Briggs, a longtime staffer from Sanders’s Senate office. In 2016, the splits led to discord in Sanders’s world.

“There was genuine disagreement, and fighting, and we all hated each other,” the former operative said of 2016.

But the campaign Sanders has built this time appears to be running more smoothly.

“It does not strike me as a death battle like it was last time,” said the former operative.

The composition and tenor of Sanders’s team isn’t the only major change to his campaign. His current platform is headlined by a host of new issues at the top, including an immigration reform plan with a moratorium on deportations until the system is audited, a “Green New Deal” to combat climate change and a $2.5 trillion affordable housing plan. The policies that made up the core of his last run are still there, but he has been able to broaden his message. “This time a lot of people know what the movement is about,” said Shakir, Sanders’s campaign manager.

What has changed most dramatically is the way Sanders talks about his platform. The senator, who has spent decades pushing his self-described “Democratic Socialist” vision, ran as a progressive wonk in 2016, delivering speeches that brimmed with statistics on the vast amounts of wealth held by the top 1 percent of people in this country, high healthcare costs and low wages. Now, Sanders is holding more-intimate events, where voters share their personal stories of hardship. Shakir described this as “politics becoming personal.”

“It’s about breaking the silence and breaking the shame that exists in public around how we discuss these very difficult matters,” Shakir said. “Did Alzheimers drive your family into bankruptcy? Those kinds of things are very difficult, but he teases them out in a very compelling and compassionate way in these town halls.”

Shakir further said the decision to add that personal touch came from Sanders himself.

“The leadership of strategy for this campaign, of how it should fundamentally go, is driven by Bernie,” said Shakir.

Though Sanders may be his own chief strategist, multiple sources who have worked with him said part of what has changed his approach from 2016 is a willingness to listen and take more input from his staff. That’s a major shift for someone who, according to a source who worked on the last race, insisted on personally editing every fundraising email.

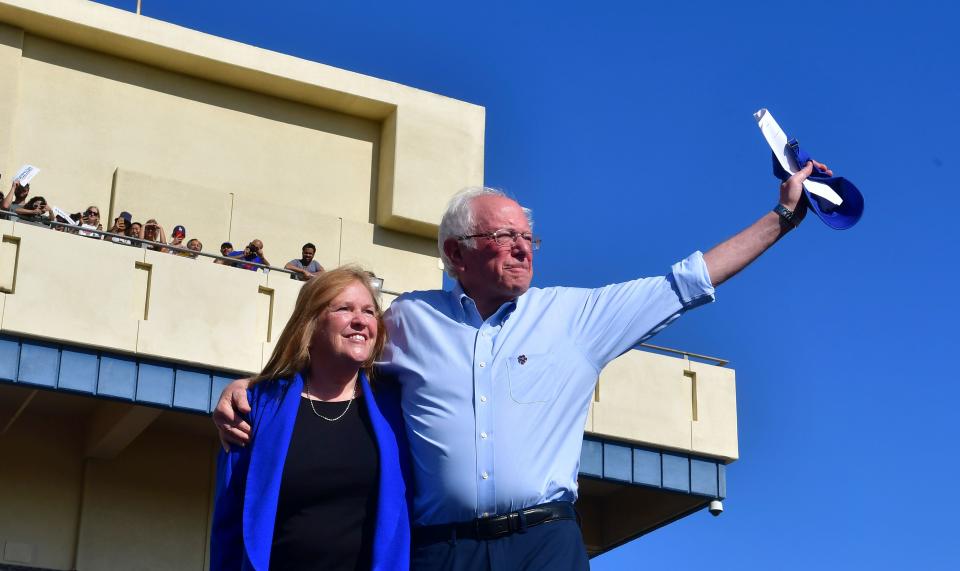

Another crucial component of the campaign has been Sanders’s wife, Jane Sanders, who Shakir says has been “giving input on all of the major decisions.”

Jane campaigned for Sanders in Iowa this week as the senator remained in Washington for President Trump’s impeachment trial. At a town hall on Friday, she shared the story of how they first met when he was running for mayor in Burlington, Vt., and came to a debate hosted by a community group where she worked as an organizer.

Both Shakir and Weaver, the senior adviser, said the decision to make more personal, emotional policy appeals was driven by the senator and his wife. In an interview with Yahoo News after Friday’s town hall, Jane Sanders noted that her husband has tended to “talk policy” throughout his political career but said that began to change as he met with voters and activists in the years since taking aim at the White House.

“Bernie, when he was younger — I’ve known him for almost 40 years — he was more cerebral, more fact driven, more data driven, more driven entirely by we have to make change from an intellectual point of view,” Jane Sanders said. “Over the years … especially this presidential campaign, with so many people hurting, he has become more driven by compassion. … He’s always done it from a policy point of view. It’s his belief system, but now, it’s very strongly his heart.”

Along with featuring personal stories from voters, Sanders has shared more of his own past on the campaign trail. The senator has given a series of interviews where he discussed his experience of growing up in Brooklyn, N.Y., as the son of working class Jewish immigrants, seeing the Holocaust decimate much of his father’s family and losing his mother to an illness shortly after he finished high school. Jane Sanders said these experiences shape his commitment to progressive politics while also making it hard for him to talk about the personal factors that fueled his views.

“His message ‘not me, us’ carries it through all the way,” she said. “He basically doesn’t like to talk about himself. He wants to talk about you, about her, about him, whatever other people’s experiences are, because he doesn’t think his experiences are as important as theirs.”

Sanders’s advisers eagerly developed plans for a more intimate and sentimental campaign. In the weeks leading up to Sanders’s announcement, Mark Longabaugh drew up a blueprint for the first months of the current campaign. Longabaugh was a member of Sanders’s 2016 media team and was a partner at the consulting firm that was run by Sanders’s former chief strategist, Tad Devine. Multiple sources said this document became known as the “Human Bernie Memo” among staffers, because it focused on telling the senator’s personal story.

Shortly after Sanders announced his 2020 bid, Devine and his firm announced they would be “stepping away” from the campaign. At the time, sources described the breakup as the result of strategic differences. Nevertheless, elements of the Human Bernie Memo made their way into the initial phase of Sanders’s current run, including the decision to launch the campaign with a speech at Brooklyn College that highlighted the senator’s roots.

Since then, along with the small town halls featuring voter stories and the interviews about his childhood, Shakir noted Sanders has shared his personality in other ways, including showcasing his love of sports and appearances with his family. For Shakir, this allows voters to see “a true version of who Bernie Sanders is in a three-dimensional way.”

“He’s funny. How many times have you seen him be funny on the course of this campaign? … We put him in these circumstances where the true Bernie character, who he is, shines through,” explained Shakir. “In addition to him being funny, you see him playing sports. … It wasn’t a concoction, it is who he is.”

While Sanders’s October heart attack sparked questions about his age, Shakir suggested the process also helped the candidate let loose on the trail. He described Sanders as feeling run down in the months leading up to the incident and said the senator began dramatically improving after he received a stent surgery in its aftermath.

“He keeps working his ass off. He feels good,” said Shakir.

The personal flourishes clearly seem to be working for Sanders. Polls show him with a growing lead over former Vice President Joe Biden in the first two states where voters will head to the polls, Iowa and New Hampshire. Sanders’s campaign has even been getting questions from multiple media outlets about who he might pick as a running mate. On the trail, Sanders has only said he wouldn’t select an “old white guy.”

Members of his team wouldn’t elaborate on this, much beyond saying Sanders is conscious of his age and wants to choose someone with experience who would be ready to take over in the event anything should happen to him.

“Most importantly, he just wants someone who can carry on and push this movement in the direction that he has been building it for his adult life,” Shakir said of Sanders. “He’s not going to be naive about the fact that he’s 78 years old. He had a heart attack. He will think about somebody who will carry this on.”

Of course, it’s far too early for Sanders to start making plans for the nomination. While Sanders has a lead in the earliest states, Biden is ahead in the third and fourth races on the calendar — South Carolina and Nevada. Biden is also still in front in national polls.

And as Sanders has become a frontrunner, he’s also faced mounting attacks. Moderate and conservative groups have announced plans in recent weeks to invest money in the race in an effort to boost Sanders’s rivals. Last month, Biden and Sanders got into an extended back-and-forth about Social Security that included ads from both sides, with each accusing the other of misrepresenting their respective positions.

Responding to those attacks represents a potential pitfall for Sanders, who built his national brand on a blend of unapologetically progressive policies and a scrappy, underdog appeal.

“When you’re in first place everybody is shooting at the same target, and that’s your back,” Weaver said.

Last month, Sanders also became embroiled in a contentious exchange with Warren after CNN published a story saying he told her that a woman could not win the presidential election in a late 2018 private event before they both launched their campaigns. Sanders denied the account and said he had told Warren President Trump would “weaponize whatever he could,” including misogyny, in an effort to win.

Warren subsequently released a statement saying Sanders had indeed told her a woman could not win the race. The discrepancy culminated in an intense exchange on stage following the Jan.14 democratic presidential debate.

In the wake of that incident, multiple sources said Sanders spoke with women on his staff in multiple meetings and phone calls and asked for their thoughts on the dispute and ideas for how to move forward. Sources also said he and Warren eventually discussed the exchange together.

Warren’s campaign declined to comment on the matter. In an interview with CBS late last month, she said, “I’ve said all I’m going to say about that.”

While the controversy over the conversation with Warren has died down, the fallout highlighted a fundamental issue for Sanders, who has built a brand as someone who doesn’t run negative campaigns. Underdogs don’t need to go negative, because they’re not usually being attacked, but frontrunners have to protect their position. “When you’re in first, it’s a lot harder to get away with it, and that’s the struggle they’re running into,” said the former Sanders operative.

Sanders and his team have maintained all of his criticisms of opponents are focused on policy and not personal. However, the former Sanders operative said that’s “a nuance that gets lost on voters” who dislike seeing candidates take shots at members of their party.

It’s a dilemma the campaign acknowledges. Weaver, Sanders’s senior adviser, described drawing policy comparisons with rivals as a delicate balancing act.

“You have to be careful about tone and you have to be careful that you’re sticking to the policy you’re discussing, because if it becomes personal in even a minor way, it blows up,” Weaver said.

As it weighs the costs and benefits of criticizing opponents, one target the Sanders campaign hasn’t shied away from is the Democratic National Committee.

On Friday, Weaver and other campaign surrogates criticized a debate rule change announced by the party last week. They charged the DNC with trying to help billionaire candidate Michael Bloomberg, who had not qualified for prior debates.

A DNC spokeswoman dismissed those allegations as “outrageous.”

Yet that sparring reflects that, as much as the one-time “underdog” campaign has evolved, a common thread remaining in Sanders’s team’s DNA appears to be the belief that the political establishment is eager to stop his rise, even as he emerges in front.

“You take any controversy of this campaign, it’s a derivative of what the true problem is,” said Shakir. “The true problem is they don’t want Bernie Sanders to win.”

Read more from Yahoo News: